I was surrounded by books as I grew up, but in the first few years of my life I paid no particular attention to the actual objects themselves. If the pages inside a book were relevant to me, I was naturally interested in what they contained — pictures, alphabets, big words and, then, with comic books, the frames that carried the story, how they were drawn, how the words fit into the speech bubbles and so on.

When I was about eight, I contracted measles and was laid up for a few days. On an impulse, my mother went and bought me an Enid Blyton book from Oxford Bookstore on Park Street — The Mystery of the Missing Man, a Five Find-Outers adventure. With nothing else to do in that pre-TV, pre-internet, pre-smartphone world, I finished the book within three or four days. On finishing it, for the first time, I was filled with what one could call ‘book-finish regret’: I felt exiled from the world of the small English village that I had inhabited so intensely on closing the back cover. The book was a hardcover with an illustrated dust jacket. Underneath the colourful dust jacket was a light blue, hard-bound volume with the name embossed in a darker blue on the front and on the spine. Suddenly, for the first time, the whole idea of ‘a book’ was tactile, palpable. I immediately asked my mother for another book from the same series.

Till that point, I was not a particularly avid reader, nor was my grasp of English anything to write home about. A few years later, my mother told me she had bought the book imagining it would keep me busy for a couple of weeks. Since I was now well enough to accompany her, my mother took me to a different bookshop further down Park Street — I remember it as Cambridge Book Store — and there I chose another Blyton book — they had no Find-Outers so I chose one from a series about the Secret Seven. This was a typically branded Blyton paperback with her signature enlarged on the cover with the UK price printed as two shillings and six pence. I finished this book in two days.

In those days, a new hardback imported from the United Kingdom or America cost a whopping forty-five rupees; foreign paperbacks were a bit cheaper at around fifteen rupees but that was still steep — there was no way my parents could afford to buy me a new book every few days. After consultation with other parents, a solution was quickly found — I was taken to become a member of the Oxford Lending Library, which was located in the low-ceilinged bunker behind the main bookstore and ruled over by a cactusy Parsi gentleman of some indeterminate old age. Here, among the shelves of the lending library, I immersed myself not only in reading but also in the whole physical mystique of bound printed paper and board. These days, whenever people speak of the difficulty of bottling various smells, I immediately want to travel back in time with some olfactory device to capture the ineffable waft of those ageing volumes of mostly English and American fiction.

When I finally did make it to spend some time in the English countryside, I looked but failed to find the real versions of Blyton’s fictional village of Peterswood and her other locales; spending a little time in English libraries, I kept searching for that smell from Park Street, but again to no avail — clearly that special scent was a result of a marriage between Western paper, printing ink, bookbinding materials, the particular tropical conditions produced by 20th-century Calcutta and, possibly, some kind of naphthalene.

From inside the Oxford Bookstore and out, books as objects turned into a lifelong obsession. Around me, the Calcutta of the 1960s and the 1970s had many parallel book universes. There were the books in my own house, a lot of them Gujarati books, some of them written by my father, others that my mother carried with her to teach in her college classes. With my eyes closed, I could tell the different feel from the ‘English’ books I was reading — the board or paper covers were of a different quality, the letterpress printing was never quite replaced by offset and, yes, the paper and the binding smelled very different. On the pavements of Park Street and in the stalls on Free School Street was a paperback cosmos, the wads of pages yellowed from age and humidity, the covers of the old bestsellers and obscure sex manuals curled and damaged in strange ways, the spines gone concave from many re-readings. After all this, when I joined college and discovered the shops on College Street, everything book-wise that I’d experienced earlier suddenly seemed limited — here were small canyons of knowledge and thought carried beyond imaginable levels of absurdity.

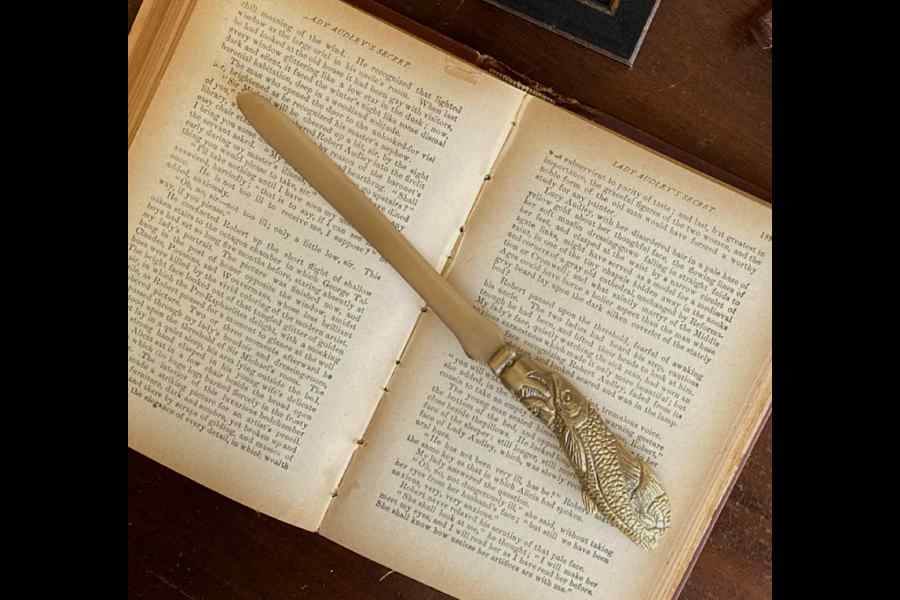

There was a pleasure in reading old books and a somewhat different thrill in opening a brand new book. Just when I began to think I knew everything there was to know about books, I went to see an older friend who was the son of a great scholar and teacher who we referred to as the Prof. I loved to enter the Prof’s house with the bookshelves teetering over the winding stairway which always reminded me of the etchings of M.C. Escher. One day, my friend and I were hanging around in the Prof’s untenanted study when a parcel arrived from the US. Inside was a book with an accompanying letter from the publisher asking the Prof to please have a look. “A new novel by E.L. Doctorow!” I exclaimed. I’d read Doctorow’s Ragtime and was a bit of a fan. I opened the mint-fresh volume and went into a small shock — the pages inside were all joined in a kind of stiff origami. “How do you read this?” I spluttered. My friend rolled his eyes and picked up an object from his father’s desk. “Do you know what this is?” Yes, I knew what a letter-opener was, thank you. It was then explained to me that proper, old-fashioned volumes always came with the folios joined; you employed a letter-opener to slice open each page as you progressed.

I was reminded of this moment recently while trying to teach a popular American novel to a class of undergraduates at a university. Fifty years ago, Calcutta kids of my background had quickly devoured the novel (the younger ones surreptitiously), making short work of its mix of some sex and lots of violence. Two weeks into the course, my students were still struggling with the first part of the book (admittedly while juggling other courses). When I asked where people had reached, I expected the answers in page numbers. What I got was a medley of confusing replies indicating that most of the students were reading it digitally. Having roughly pinned down the percentage of the text that had been collectively processed, I visited a friend for the weekend. Looking through his bookshelves, I picked out The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, a novel by David Mitchell I’d been meaning to read for a while. Turning the hardback over in my hands, I noted the beautifully designed dust jacket. But what pleased me even more was that the edges of the pages were deckled and uneven, almost as if they had been cut open by a letter-opener.