“Among kings and aristocrats,” the historian, Abraham Eraly, wrote in the book, The Mughal World, “weddings were elaborate, fabulous affairs, involving vast expenditure — for Dara’s wedding with Parvez’s daughter, for instance, Shah Jahan, according to Inayat Khan, spent in all 3.2 million rupees.” We are told the weddings of Mughal aristocracy took place a few weeks after the engagement, to give space for organising festivities.

That sounds rather modest compared to the seven-month-long wedding opera organised by India’s top business oligarch, Mukesh Ambani, at an estimated cost of over half a billion dollars. There are two remarkable facets about this ostentatious splurging of wealth, live-streamed to the world, in the wider socio-political context. One, the absence of any marked social outrage or cultural revulsion. Indeed, millions of people enthusiastically conformed to the media’s nudges to vicariously consume every last detail of this celebratory gala. What explains this popular buy-in to hook onto a fantasy lifeworld of the rich and the famous so far removed from the world they inhabit?

After all, India remains a relatively poor country with booming inequality. The bottom half of the population as well as large sections of the lower-middle classes eke out a precarious existence. The latest household expenditure survey showed that almost one half of the total expenditure of an average Indian household is still spent on purchasing food items (46% in rural areas and 39% in urban areas). Real wages for the bulk of the workforce have remained stagnant for much of the last decade, as per the Periodic Labour Force Survey data. More strikingly, net household savings shrivelled this year to their lowest mark in five decades. At the same time, the wealth concentrated within the richest 1% of India’s population has peaked to its highest level in six decades, constituting over 40% of the total wealth of the country, according to a report by the World Inequality Lab.

A recent article in a business daily dubbed the country’s consumption story as “a baffling tale of contrasts”. “Luxury apartments, fancy cars and top-end consumer goods are flying off the shelves. Malls and restaurants are full while hotel rooms are pricier than ever amid surging demand… Meanwhile, FMCG companies are looking on enviously, unable to sell as much of biscuits, soaps, shampoos and perfumes as they would like,” the report stated. Such a socio-economic context can easily give way to a resentful popular mood. A public gaze reflective of a conscious citizenry might well have viewed with scorn the collaborative networks of economic, political and cultural elites huddled together in czarist splendour. The public gaze, however, was akin to that of a passive mass of consumers and spectators, lending the ‘mega-event’ popular legitimacy through tacit acceptance if not starry-eyed approval.

The second remarkable facet is the absence of any attempt at political mobilisation on the platform of soaring inequality by framing the wedding affair as a ‘lightning rod’ issue. These are the kind of issues that, as sociologists argue, carry the potential to crystallise popular grievances and provide the necessary shock that arouses latent moral feelings of outrage or shame. Furthermore, they provide fateful openings for political parties to forcefully articulate popular demands as well as clarify their distinctive platforms.

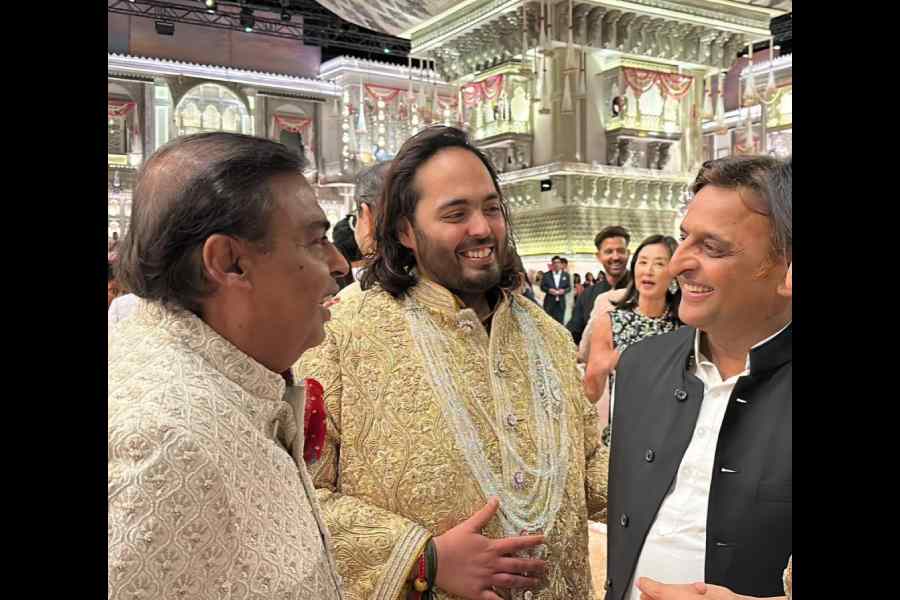

None of this happened. Instead, leading figures cutting across the Opposition INDIA group dutifully graced the wedding much like the prime minister. They include Mamata Banerjee, Akhilesh Yadav, Uddhav Thackeray, Sharad Pawar, and a host of Congress leaders, from D.K. Shivakumar to Kamal Nath.

It would, therefore, be facile to blame the public. But it would also be a mistake to portray them as naïve or indoctrinated. The India Today Mood of the Nation survey conducted earlier this year bears this out. On the question probing which sections are seen to have benefited most from incumbent government policies, 52% said big businesses, compared to 9% for farmers, 8% for the salaried classes and 6% for daily wage labourers. A plurality (45%) blamed government policies for widening the gap between the rich and the poor. A majority (62%) claimed difficulty in managing household expenses. Three-quarters estimated their future incomes would stay stagnant or worsen. This is not a populace harbouring any illusion about its situation or the fact that its relative deprivation stems partly from State policies. It is, however, a cynical populace which does not see a credible alternative that can deliver any structural transformation.

In other words, it recognises the country as constituting a ‘simulated democracy’. The political scientists, György Lengyel and Gabriella Ilonszki, employed the concept of simulated democracy to describe the post-Soviet democracy of Hungary along with some of its neighbouring countries. They provide four characteristic features marking such a democracy. One, weak elite adherence to norms and rules of democracy “behind its scenery of democratic institutions”. Corruption is baked into the political system, making democratic institutions ineffective in practice. Second, a “tacit elite consensus” on fundamental political questions, such as the role of the State and markets. All parties remain committed to safeguarding the existing institutional arrangements, a shared source of instrumental benefit. Third, co-opted civil society organisations, such as the media and the trade unions, which “aid and abet ways in which the most important elite groups profits.” And fourth (as a consequence), a citizenry having “a low level of confidence and trust in politicians”, leading to a “disenchanted and partially inert electorate.”

All four features are patently applicable, in large measures, to Indian democracy. These features not only pre-date the rise of the Narendra Modi era but also help us understand the context which led to it. The political scientist, Ashutosh Varshney, has written on the disjuncture between mass politics and elite politics in relation to India’s economic reforms. Post 1990s, while mass politics remained an adversarial hotbed of ethnic issues of caste and religion, the issues of economic distribution and social welfare were quietly depoliticised, generating a neoliberal “common-sense”.

One doesn’t need to be a political scientist to grasp the deeply constrained nature of Indian democracy for it is keenly felt by the ordinary people. A 2018 survey conducted by CSDS-Lokniti had found that political parties carried a negative net trust rate of -55% (calculated as the percentage of respondent who trust them minus the percentage who do not). They were the only institutions with a negative trust rate.

The sustenance of simulated democracies depends upon the ability to co-opt the rising elites and ensuring a certain degree of “circulation of elites”. At a certain point, however, such limited circulation of elites, functioning within a narrow policy consensus, seems unable to channel the rising expectations of the electorate. This is when simulated democracies devolve into a further pathology: the yearning for a transformational leader who would “drain the swamp” from the grasp of its incestuous, cross-pollinating elites. We have witnessed two such transformative leaders in our democratic evolution: Indira Gandhi and Narendra Modi. Both leaders promised a structural transformation even as their efforts remained confined to half-baked populist manoeuvres and an ill-advised centralisation of authority.

“But such transformational zeal overlooks why and how the ‘swamp’ needs draining. When combined with a disregard for popular hopes and expectations, transformational leadership is not a promising recipe for democratic politics,” wrote Lengyel and Ilonszki.

There is still a way out for Indian democracy beyond the illusory choices of simulated democracy and electoral autocracy. That is the path towards a consolidated democracy: a democracy where the demos (ordinary people) finally wrench substantive power from the shape-shifting networks of the ruling elites.

For starters, it would require a coherent, counter-hegemonic political vision; a vision for structural transformation, which frontally challenges the neoliberal “common-sense” of sanctioning unconstrained private profits and oligarchic consumption, while tarring social welfare expenditure as a “drain on resources”; a political imagination which refutes the assumption that the India growth story is synonymous with the growing wealth of billionaires; a moral consensus which prioritises equal opportunities for all and does not tolerate an apartheid education system where almost half of rural teenagers cannot read a sentence in English while children from the upper-middle classes corner premier coaching facilities.

And, lastly, a vision that shifts the popular common sense where it is no longer possible to seamlessly host the “priciest wedding of the century” in a pharaonic convention centre miles away from the streets lacking basic infrastructure, flooded by regular monsoon rains.

Asim Ali is a political researcher and columnist