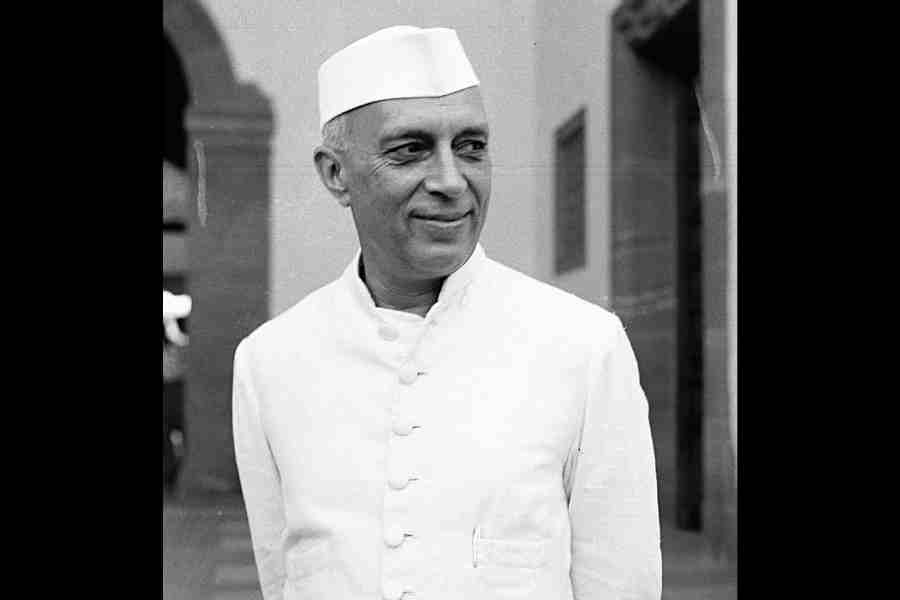

Should privacy trump public interest? If so, what is the line that separates public interest from meddling? These are some of the questions that have been thrown up in light of the ongoing tussle over the ‘private papers’ — material belonging to eminent personalities that are not in the public domain and belong to their legal heirs — of the first prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru’s papers were originally donated to the Prime Ministers Museum & Library — it was formerly named after him — by Indira Gandhi, but a tranche of these were reclaimed by Sonia Gandhi in 2008. She also barred access to several sets of papers still with the PMML. This has prompted the museum to decide that it will not permit future donors of private papers to impose

indefinite conditions on the declassification of such material.

The PMML has the largest collection of private papers in the country. Originally belonging to some of modern India’s most influential figures, including Mahatma Gandhi, B.R. Ambedkar, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Bhikaji Cama, Sundarlal Bahuguna and many others, these were mostly donated by their family members for safekeeping and conservation. Many of those who donated such private papers to the PMML set unspecified embargo conditions concerning public access to these. As a result, the institution is a repository for such sensitive documents and conserves them, but cannot make them public for the lay citizen or researcher.

There are two — conflicting — lines of thought as far as these documents are concerned. Private papers are deemed invaluable by scholars for an accurate appraisal of the lives and the times of these tall leaders and even for comprehending modern India’s genesis, its history, its architects and watershed moments. But there are others who argue that declassification can lead to the infringement of the privacy of these august personalities. This argument ought not to be dismissed since it cannot be denied that the curiosity about the lives of eminent people may not always be innocent — for instance, several members of the PMML Society have insisted on retrieving from Sonia Gandhi the correspondence between Nehru and Edwina Mountbatten. It must be remembered that the PMML operates under the aegis of the Central government. Therefore, the possibility of weaponising institutions to settle political scores cannot be ruled out.

There are no easy answers when it comes to deciding whether the collective right to historical papers should be prioritised over the private right of ownership of personal documents of icons. International templates, in fact, give a slight advantage to the powers that be. In the United States of America, it is the government that has the last say over papers with the Library of Congress Manuscript Division; in the United Kingdom, the decision rests with the monarch and the government. But alternative templates can be thought of. Treating requests of publication of such papers on a case-by-case basis after rigorous consultation with all stakeholders, including the family members of the deceased, independent scholars and the State, would not only offer a way out of dilemmas but also honour the ethos of democracy.