As a child, I would be forced to listen to All India Radio when my father tuned in to the broadcasts of khayal in the morning. With the acquisition of a radiogram and its record player came the competing needs of different members of the family: bhajans and Hindi songs for my mother, North Indian classical for my father, and whatever my Western pop and rock sensibilities demanded at the time. While I could handle the Hindi film music, the bhajans and even Rabindrasangeet, I drew the line at what I called the ‘gargling’ of Hindustani vocalists and what seemed to me the pointless twanging of Ravi Shankar et al. All this changed when I went off to boarding school in Rajasthan, far away from home. The mounting homesickness at school crystallized one morning when the principal put on a record of Omkarnath Thakur for the daily piece of music he would play in the assembly. Suddenly, the gayaki became the sound of the home I was missing and I found myself savouring it.

Returning home for the holidays, I found myself listening to more and more of Hindustani classical. By the time I got into college, I was into shastriya sangeet, both vocal and instrumental, having even discovered some twangists who appealed to me, such as Vilayat Khan and Nikhil Banerjee.

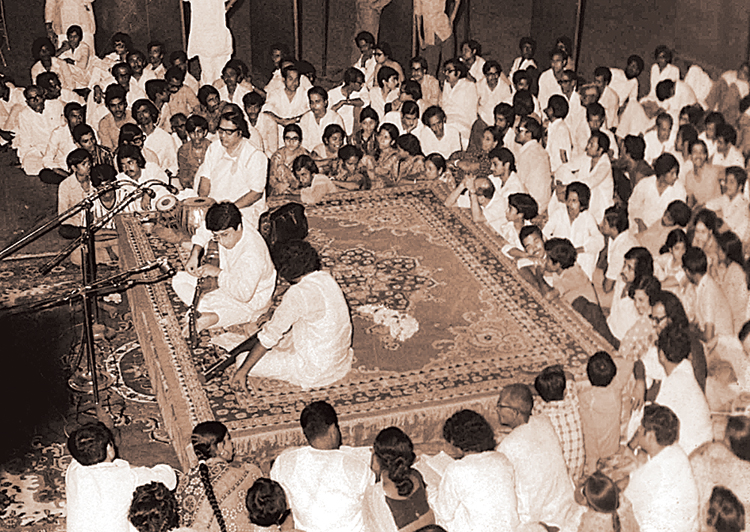

At some point in the 1970s, I began to attend live concerts. Before this, my definition of a ‘concert’ was overcoloured by the typical spectacle of a Western orchestra and by rock and jazz performances mostly seen in photos and films. Going to a Hindustani music performance, I missed the dramatic illumination one associated with these Western configurations. But once the musicians began to weave their web, nothing mattered but the experience of witnessing this magical, never-to- be-repeated act of aural creation. All other stuff, the backdrop and the lighting, became irrelevant as you were drawn into the raga; all you needed was to see the faces and hands of the musicians clearly, to enjoy the expressions, the blur of fingers, and the exchange of looks.

The Calcutta of the late 1970s was rich with gifts for the aficionado of Indian classical music. Once, completely ignorant about this music called ‘dhrupad’, I wound my reluctant way to a concert by some ‘Dagar Brothers’ at the Bhawanipur Education Society, not expecting to stay very long. I came out hours later feeling my life had been transformed. Foolish but fortunate, the first time I got to hear dhrupad it was sung by Zahiruddin and Faiyazuddin Dagar.

Cool January would bring Dover Lane and in those days you could get in at the last moment with affordable tickets. You sat in the back, with the trams jangling by on the main road, taking surreptitious swigs from whatever bottle you had smuggled in, with friends charging their cigarettes with ganja. As the evening progressed into the winter night, you sneaked forward, finding empty seats that had opened up closer to the stage. By the time the main artist came on, you were on a double or triple high, but never so merry that you didn’t notice if the great man was himself legless as he wove his way to the takhat, never so gone that you missed the legendary voice sent off-key or the sarod string sent snapping by too much Scotch. For every such occasion, there were many more moments of the deepest epiphany as some genius, she or he, faultlessly raised the level of your consciousness to a place it had never previously reached. On those days, you stumbled out into the dawn light, all base inebriations erased by a much more powerful intoxication.

Across the years, you learned to grasp the gift of the music without allowing the mise en scène to interfere. Many concerts were under bright lights, with garish banners proclaiming the name of the sanstha under the auspices of which the event was taking place; sometimes the sound would leave a lot to be desired, but you learned to concentrate on the performer and the music. Sometimes, the aesthetics of the stage would be quite wonderful, understated, or even opulent, such as in some haveli or fort, supportive of the performance rather than going counter to it and for this you were thankful — it required less work from you as a shrota. The more performances you attended, the clearer it became that sometimes the badly presented event gave you great music while some of the over-designed chi-chi frou-frou presentations failed to make up for dud performances. Till recently, I imagined that in terms of classical Indian music I’d seen it all as far as staging and presentation went, from intimate mehfils to grand theatres, from decrepit venues to concert halls with specialized acoustics.

The other day, I went for a Carnatic concert in Chennai. The vocalist my friend and I were going to see came from great lineages of Carnatic music and has a growing reputation. The Kamarajar Arangam is a massive old hall on Mount Road. At the top of the grand flight of stairs that reminded me of Rabindra Sadan was a small desk where the tickets were being sold. On the walls of the large foyer was an array of old portraits. The age and dustiness of the chipped frames would make any communist party office in Bengal very proud, except these were photos of Congress Party leaders. Entering the theatre, the timeless decrepitude of the place created hope — a typical, unfussy South Indian milieu, no show-sha, concerned only with the substance with no unnecessary fripperies, therefore the music would be superb.

With the curtain rising, a shock. The stage was lit as though for a wedding reception of the son of a nouveau riche mining magnate. The ‘wings’ at the sides were huge vertical digital screens flashing the sponsor logos, while behind the takhat a bigger screen ran pictures of various deities. The singer started on the ragam. The sound landed on the seats like artillery shells. A battery of lights facing the audience blinded us while video cameras collected their first pound of footage. The singer stampeded into precipitate ecstasies. The flipping logos matched the beat of the mridangam. The big screen flamed into a lurid orange and then back to the parade of gods. The vocalist, clearly highly skilled but not, on available evidence, blessed with any extra mellifluousity, entered into a jugalbandi with the violinist. This was, however, dwarfed by the jugalbandi between the wing screens and the backdrop screen. The musicians disappeared in the rapid fire of digital colours while the sound bounced off the torn seats as if aliens were attacking the old place from a new spaceship. After about 40 minutes, my friend and I made our way past the senior members of the scattered audience, careful not to wake them. I didn’t scan the audience thoroughly but I didn’t see anyone there below middle-age. Had I been a teenager today, just becoming interested in this music, I would have run away very fast from this disastrous disco.