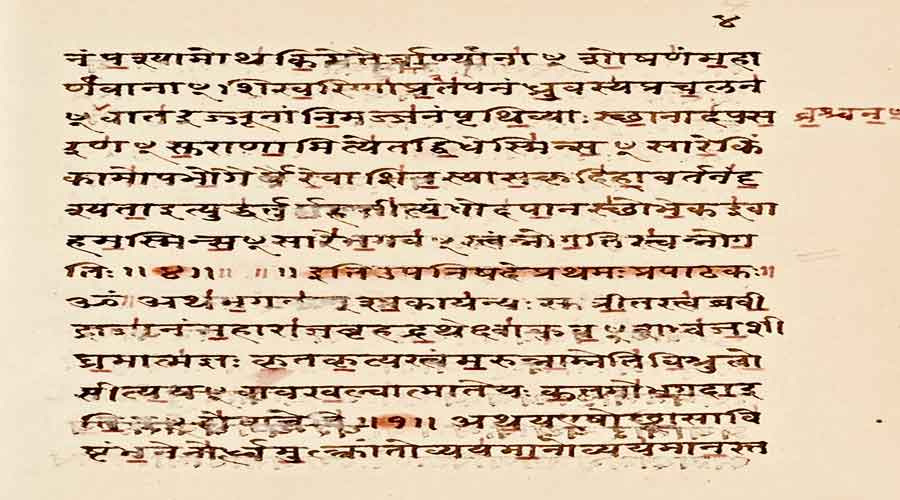

Despite India’s claim to be modern, traditions, including the textual tradition, continue to be a significant part of Indian life and thought. There are two aspects of the textual tradition: ideas and method. While ideas may be accepted by some and rejected by others, methods, such as debates or compilations on the other hand, can be revisited as they are considered less controversial. India has a rich and plural tradition of compiling different sutras, an exciting instance being Badarayana’s composition of the Vedanta Sutra.

However, despite the tremendous achievement of systematically compiling the Upanishads, Badarayana seems to have not been given his due. Books on Indian philosophies prominently feature the Vedanta. Within the Vedanta, Sankara’s Advaita, Madhva’s Dvaita, Ramanuja’s Visistadvaita, Vallabha’s Shuddha Advaita and Nimbarka’s Dwaita Advaita occupy centre stage, although in varying degrees. It is important to note that all these bhasyas or interpretations are based not on different sutras but Badarayana’s Vedanta Sutra.

Despite this convergence, bhasyas remain dominant in the discussion on Vedanta, almost overshadowing the sutra. This trend continues in the reception of Vedanta in modern India, both amongst scholars as well as public thinkers. This is despite the active engagement of the bhasyas with the sutra. Further, each bhasya competes with other bhasyas in claiming to be an authentic interpretation of the sutra. There are specific issues surrounding this relationship.

First, within Indian scholarship, there is a lack of recognition of the importance of compilation. Compiling as a specific and distinctive method involves a careful engagement with the works or ideas of others and is a distinct genre. In accomplishing the compilation, Badarayana made a fundamental contribution to the growth and diversity of Vedanta, especially concerning form and method in addition to contents. This aspect of Vedanta, achieved during a phase that precedes the bhasyas, deserves more attention and should not be glossed over.

Further, the timing and the reason behind the compilation are equally important. The Upanishads, which are exploration and inquiry, are diverse and plural. The need to consolidate these teachings into a systematic body of knowledge on Brahman and Atma could have been the reason behind the compilation. Or it may have been the desire to defend the Upanishads against the onslaught of rival philosophies like Buddhism. This sensitivity to the context is one of the reasons why Badarayana is so important.

Second, we need to consider the critical cultural differences between Indian and Western philosophy. For instance, in the West, the original text of important philosophical works is featured prominently, be it Plato’s compilation of dialogues, Aristotle’s The Metaphysics and Politics from Greek philosophy, the Bible from Christian theology, or even Descartes’s Discourse on Method or Meditations on First Philosophy in modern times. Interpretations of these philosophical works do not feature as conspicuously as the original texts in Western philosophy. Also, hermeneutic philosophy — from Rudolf Bultmann, Hans-Georg Gadamer to Jacques Derrida and deconstruction — is positioned to combat the hegemony of the text. It revolts against the author’s authority, aims to liberate the text from the author, and makes a case for the importance of interpretations. This contrast with Indian philosophy should encourage us to reflect on the effects of the routine teaching of these post-structural philosophers in Indian universities.

Badarayana is also relevant for yet another reason. A unique aspect of nationalist leaders from India is that they are both serious political leaders and prolific writers. This combination is unprecedented in the world. Bal Gangadhar Tilak wrote works on the Vedas in addition to his monumental Gita Rahasya. Vivekananda’s writings are collected in ten volumes, Aurobindo’s and Ambedkar’s writings in 30 volumes each, and Gandhi’s in 100 volumes. These writings are less systematic, often contradictory, and are entrenched in the context. However, there are rich ideas spread across these texts.

While these modern Indian writers may not have presented readily accessible theories, once their diverse writings are put together systematically, the compilations can provide an opportunity to derive different interpretations reminiscent of the bhasyas. Despite certain limitations, classical philosophies from the Indian subcontinent too can present a variety of rigorous systems in stark contrast to classical philosophies from the West.

Modern India, however, has fallen behind in contributing new ideas to the contemporary West. These modern Indian philosophical texts can begin to fill this gap if they are presented as systematic compilations. On the other hand, presenting them without any systemizing or organization would put the Indian writers at a disadvantage, making them appear weak and vulnerable compared to philosophers from the modern West.

The absence of Badarayana, the foundational compiler, points to a glaring chasm in our understanding of Indian philosophical traditions. Not studying the methodology of compilation formulated by him; not paying enough attention to the sensitivity he displayed to the changing context around him; not recognizing that the Indian experience of domination of the bhasyas over the sutra is radically different from the hermeneutics of the West; and, most importantly, not appreciating the contemporary relevance of compilation — all these reveal serious gaps in the way we currently read traditional philosophies.

Revisiting traditions with modern relevance can bring new aspects to the forefront and help rejuvenate interest in the classical tradition — a dynamic tradition being less oppressive than a frozen and static one.

(A. Raghuramaraju teaches philosophy at the Indian Institute of Technology Tirupati)