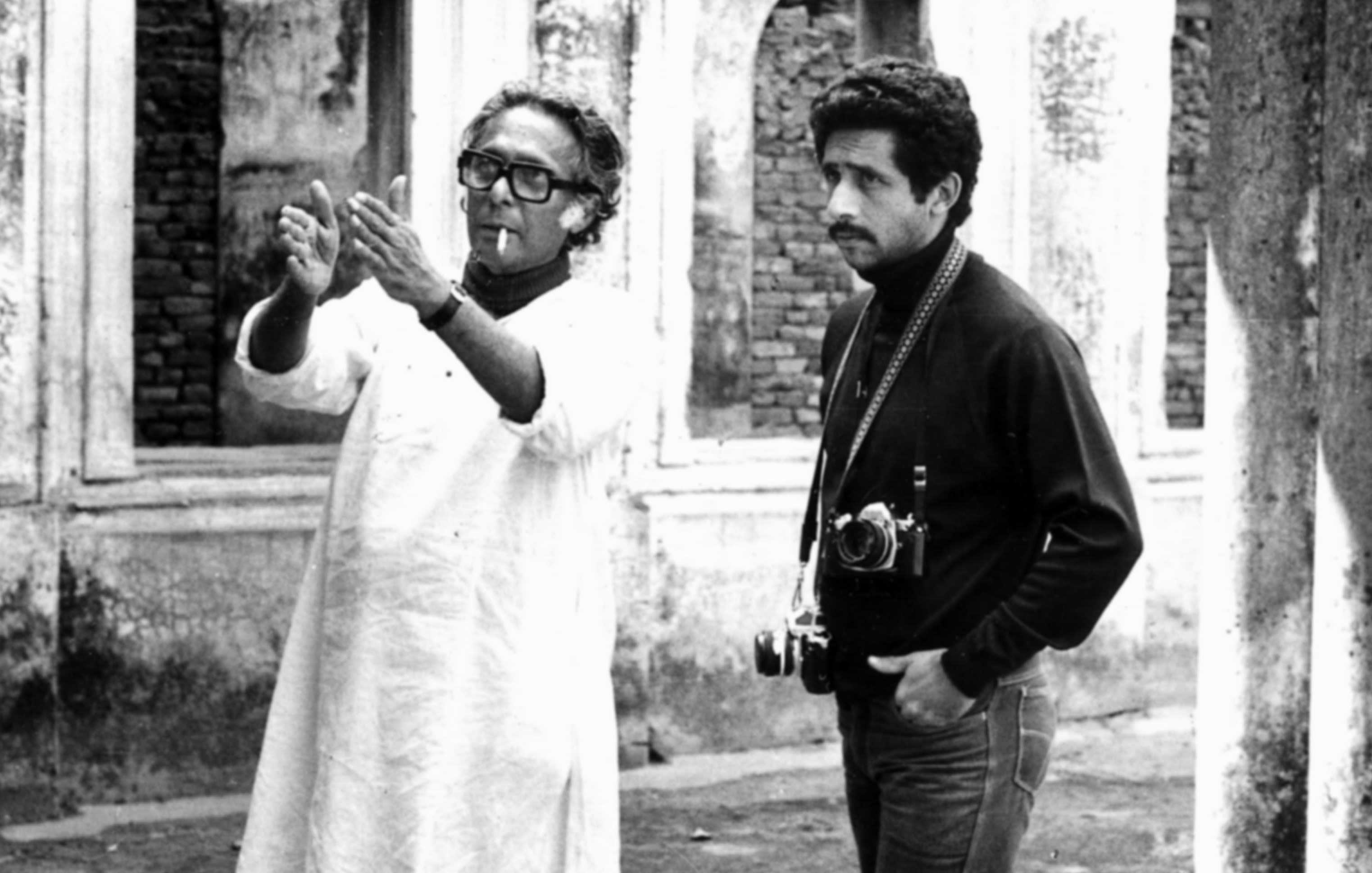

Mrinal Sen’s little-known Telugu film, Oka Oori Katha (The Outsiders, 1977), was ‘invented’ out of Premchand’s story, Kafan (Shroud). Sen, who died recently, took the story far away from the Hindi-speaking heartland to the benighted acres of Telangana and cast the great Kannada actor, Vasudeva Rao, in the central role of a savage prophet on the prowl. A blistering, absurdist critique of the relentlessly exploitative ways of a feudal landlord exacting total submission from his helpless subjects, this masterpiece showed Sen at his pan-Indian best. Told starkly and without pity, this cruel fable rested on the shenanigans of a middle-aged father and his young son who refuse to work for a living, claiming that to work in the given evil system would be to help perpetuate it.

When the son brings home a wife and she goes out to work because she is the product of a different value-system, the father and son drink away her earnings. The young woman dies at childbirth, a victim of hard work and starvation. The two men go around the village asking for money to buy a shroud, but squander the collected alms on drink. The film exerts on the viewer an intoxicating mix of anger, sadness and, what is most compelling, a deep sense of wonder at how far the artist can go when he sets his mind on giving a jolt to what he considers to be a soporific audience.

Almost all through his chequered career, Sen distinguished himself by his marked aversion to innocent storytelling. Providing safe entertainment was never a part of his artistic and intellectual principles, dependent as they were on his politics of confrontation by exposing the active or dormant hypocrisies without which the different classes can never be complete.

In this context, Sen’s words provided food for thought to the restless young souls of the time when both the city and the countryside were plunged in the turmoil of internal contradictions and external fears generated by growing State repression.

Proving true to his role of the concerned interrogator, Sen showed the father-son duo making their choice in the matter of ‘to work or not to work’ in unique, unequivocal terms. They have decided to work only when starvation forces them to; otherwise, they will sleep away their miseries; they will beg, tell lies, thieve. In between, they will rave and rant, the father repulsive yet fascinating as an argumentative avatar of naysaying. In other words, these supreme strategists have decided not to allow their toil and sweat to make the oppressor richer, stronger, more grasping. The old man tells his son, and anyone else in the village who may care to listen, that you have to be a fool to go to work because your work only serves to fatten the master who will not think twice before stealing your very loincloth. He warns his son, who has his moments of doubt, not to be trapped in the conspiracy of work — “The evil spirit of work will not let you free; if you fall into that trap, you are lost.”

For the kind of explosive examination of the landless labourer’s vital contribution to the accumulation of power in the hands of a few rural prototypes that we come across in Oka Oori Katha, the use of high decibels in several passages was essential. The drama of self-imposed destitution cocking a snook at conventional wisdom regarding the necessity of work clearly called for the kind of sound and fury that Sen employed to create a spectacle of an unequal contest between two impoverished waifs and the landlord and his men.

Sen’s ‘take’ on the futility of work when it improves the material condition of the master even as it worsens that of the servant offers a ridiculously sublime twist to the theme of rural exploitation, the kind of which had never before been seen in the history of Indian cinema. In fact, it can be argued whether such an outrageously utopian dismissal of unremunerative labour in a village society/economy masterminded and controlled by superior beings exists in world cinema.

The uniqueness of Sen’s social philosophy and the source of the undaunted nature of his art — they are expressed in his best films — come out very well when he says, “In India where except in a few cases, film-makers have hardly looked beyond what their predecessors had achieved, we need... experiments to enlarge the area of operation, experiments to mark the advent of a new genre of cinema, experiments, above all, to sharpen the medium as an instrument of social change.”

Hopefully, Oka Oori Katha will continue to be ‘read’, albeit by a slowly-growing, distinguished audience, as the epic of the ‘reasoned unreason’ that it is. Bizarre as it may sound, the film’s perverse intelligence combined with its unbearable soulfulness is of such stature as to condemn it to the status of a piece of art more feared than loved.