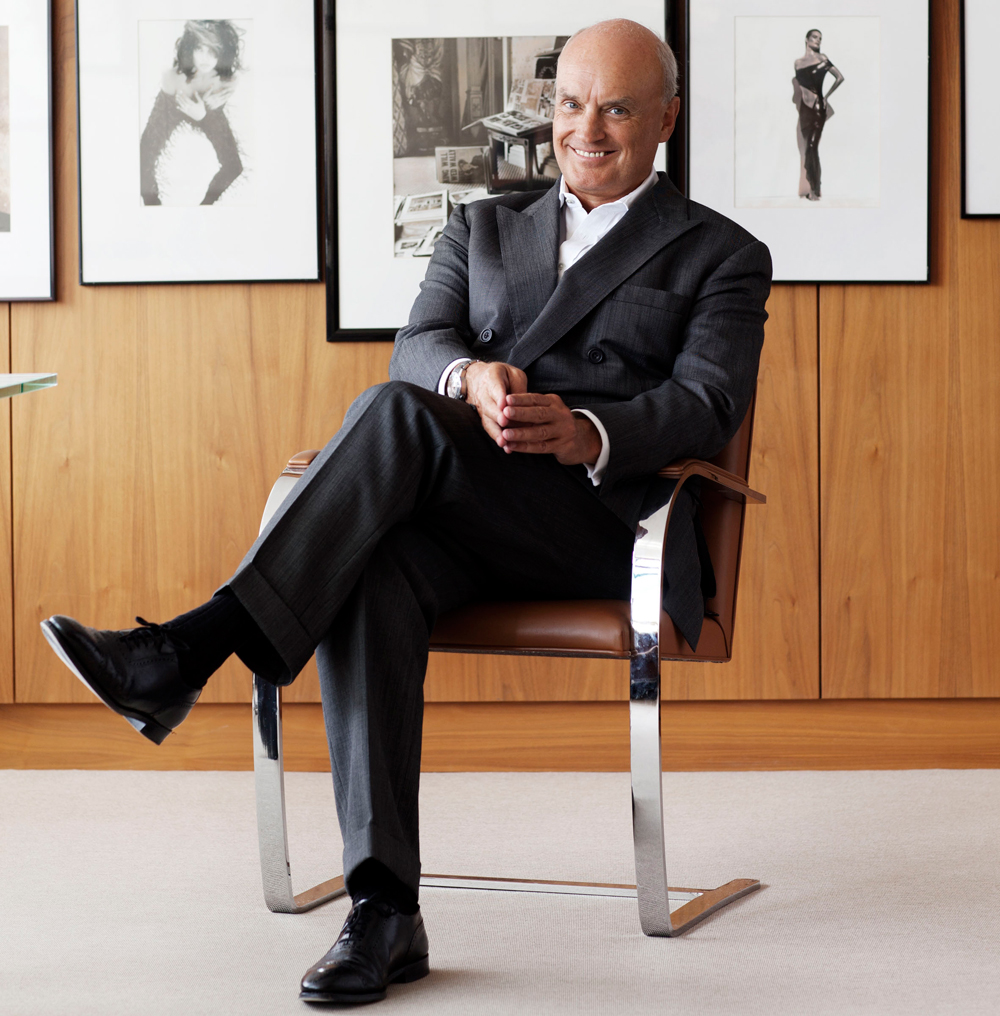

David Cameron, who was probably the most pro-India prime minister Britain has ever had, has just brought out his memoirs, For the Record. So has Nicholas Coleridge, who knows anyone worth knowing since, for 30 years, he has run Condé Nast Britain, which publishes a whole host of glossy magazines, from Vogue and GQ to Vanity Fair and Tatler. His book, billed as “gossipy, scandalous and riveting”, is aptly called The Glossy Years.

Nicholas, whom I have known for ages, tells me that someone at Vogue House counted the stamps in his passport and worked out he has been to India 88 times. Now 62, Nicholas and his wife, Georgia, who have four children, got engaged when they stayed at the Tollygunge Club in Calcutta in 1989. Upon hearing the news, Bob Wright, “that enormous big bluff Englishman who had stayed on and ran the Tollygunge Club”, responded, “How lovely. Come and have dinner on my terrace with my wife.”

They were joined by another English couple who were backpacking around India on the cheap. “They were Hugh Grant and Elizabeth Hurley and they weren’t famous in those days. Anyway, the next night I went and had dinner with Aveek and Rakhi Sarkar in that rather good house that they lived in, and it was around that time I became interested in the Indian press.” Nicholas expressed his admiration for The Telegraph and its former editor-in-chief in Paper Tigers: The Latest, Greatest Newspaper Tycoons and How They Won the World, published in 1993.

Nicholas, who is also chairman of the Victoria and Albert Museum, has cut back his previous responsibilities but retained his India brief. He finds that India has “a sort of spiritual serenity mixed with a glorious appetite for gossip which comes together to produce for me a very alluring country”. He adds: “My father, by the way, was born in the Malabar Hills and lived there till he was two.”

Raghuram Rajan's 'The Third Pillar: The Revival of Community in a Polarized World' is in the running for the £30,000 Financial Times and McKinsey Business Book of the Year Award Ranajit Nandy

Start anew

Things have been looking up for Raghuram Rajan ever since he stepped down — or was compelled to step down — as governor of the Reserve Bank of India in 2016 and returned to academic life as the Katherine Dusak Miller Distinguished Service Professor of Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Although Rajan has indicated he is not looking to succeed Mark Carney as governor of the Bank of England, he had previously been tipped for the job anyway by the Financial Times.

On Monday, I went to a lunch at the Royal Society of Arts to hear about the six titles shortlisted for the prestigious Financial Times and McKinsey Business Book of the Year Award 2019. And sure enough, Rajan’s The Third Pillar: The Revival of Community in a Polarized World is in the running for the £30,000 prize. The winner will be revealed in New York on December 3, with those who don’t win walking away with a £10,000 cheque.

Rajan has a history with this prize. He won in 2010 for another of his books, Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy.

The numbers speak

While going into the National Theatre to see a new play called Hansard, I bump into Lord Jeffrey Archer in the foyer. This is relevant because the play, written by Simon Woods, has an unkind reference to the author. It is a two-hander and is set in 1988 — when Margaret Thatcher was the prime minister — and digs deep into the dysfunctional marriage of a typical Tory parliamentarian, Robin Hesketh (played by Alex Jennings), and his stay-at-home wife of 30 years, Diana (essayed by Lindsay Duncan). At one point, she berates her husband for not reading anything literary: “When did you last read a novel?” When he points out that “I read that Jeffrey Archer over Easter,” she responds dismissively, “Jeffrey Archer doesn’t count.”

Archer, who listened to the exchange, can afford to ignore this cheap shot. A first print run of 3,00,000 has been ordered for the hardback edition of his new novel, Nothing Ventured, which was second on The Sunday Times bestseller list.

Divided opinion

The former England left-arm spinner, Monty Panesar, met Indian journalists last week to talk about his autobiography, The Full Monty, and said that he approved of the knighthood conferred on the 78-year-old Geoffrey Boycott. This has been controversial because Boycott was convicted in a French court in 1998 for assaulting his former girlfriend, Margaret Moore — something he has always denied.

One profile of the former England opener-turned-commentator included a quote from the Australian player, Dennis Lillee: “Geoffrey... fell in love with himself at an early age and has remained faithful ever since.” After interviewing Boycott for the radio, the psychiatrist, Anthony Clare confessed he would have to revise the famous line penned by the Jacobean poet, John Donne, that “no man is an island”. Ian Botham has claimed that as a player, Boycott was “totally, almost insanely, selfish”. Others insist, however, that the Yorkshireman is a national treasure.

British sculptor Antony Gormley poses under his Matrix sculpture at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, on Monday, Sept. 16, 2019. His focus on the human body was greatly influenced by living in India as a young man before he joined the Slade School of Fine Art in London AP

Footnote

Britain’s two most famous sculptors, with very different styles, are Anish Kapoor and Antony Gormley (picture). The former had his solo exhibition at the Royal Academy in 2009. Ten years on, Gormley’s solo exhibition is equally breathtaking, with statues hanging upside down from the ceiling, for example. Following a guided tour, the curator, Martin Caiger-Smith, confirms that Gormley’s focus on the human body was greatly influenced by living in India as a young man before he joined the Slade School of Fine Art in London: “He learnt about Buddhist meditation in India.”