In an interview before his death, Eduardo Galeano, one of Latin America’s foremost voices, had said, “Based on what I have experienced in my life, I have the impression that we make the history that makes us.” On one end is the humanist vision that considers history to be the result of the struggles for liberty and justice. And on the other is the anti-humanist school that regards individuals as a product of history and freedom to be a mere illusion.

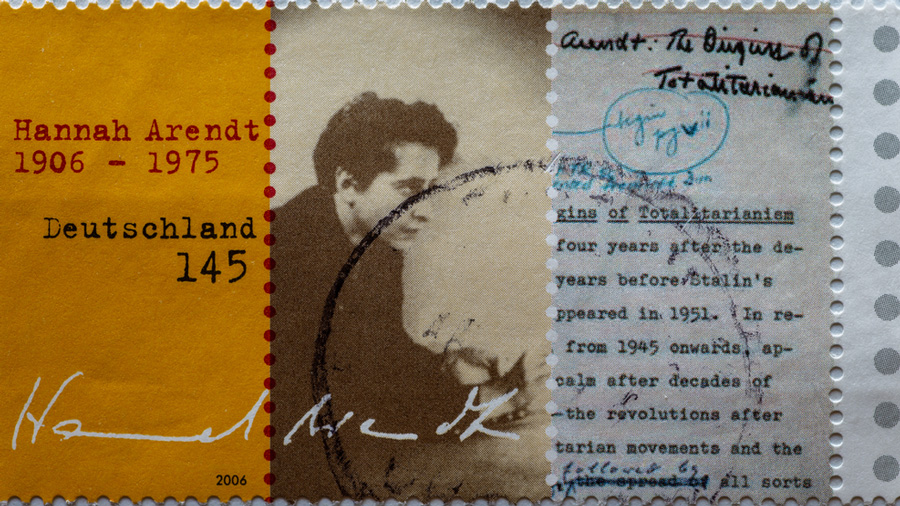

Liberal intellectuals belonging to the humanist school have, over time, encouraged the academic world to engage critically and articulate their opposition to any conformist control especially when authoritarianism and intellectual vacuity rage across the globe. The conflict has always been between a university becoming a seat of diversity and a seat of indoctrination. Freedom and restraint are the opposite poles of deciding the limits that a university could go to in expressing contentious views. Hannah Arendt’s views on the hegemony of the State with stiff control over thought and action can be applied to universities that retreat into silent acquiescence, discouraging diversity.

Familiarity with the lectures and writings of public intellectuals like Noam Chomsky, Edward Said or Terry Eagleton is a rigorous training in the multiplicity of opinions from a left libertarian point of view. This has inspired teachers and students to stand up against forces that undermine the progressive functions of a university. As advocates of emancipatory reason, of a rationalist analysis of the world, these public intellectuals validate a commitment to human freedom, inspiring young academics to regard

the classroom as an arena of political interest and bold intervention. Probing deep into history and culture, they have bequeathed on the university culture the intellectual requisite of free and frank dialogue with the spotlight on public responsibilities. This has consolidated a culture of distrust for any imposition of restraining powers on the university.

For justice

Generations of teachers and students have approved of the intensity and the social commitment inherent in the intellectual legacies of philosopher-teachers like Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin. Their endorsement of the exchange of ideas and their willingness to reflect on the opposing point of view had a profound impact on the meaning of human emancipation. They realized that the conscience was the most reliable instrument of inquiry. For these philosopher-teachers, the borders between political beliefs and existence, pedagogy and civic obligation, were blurry. An unwavering concern for social justice and the lending of a voice to the deprived became the raison d’être of their political philosophy. Boisterous and freewheeling teaching and research, exploration of the unconventional and the unexpected, and always holding orthodox assumptions to critical scrutiny became the guiding principles of a free mind. The acceptance of alternative discourse and engaging in debates on the basis of rationality imbued generations with an attitude that balanced tolerance with scepticism.

With left politics having taken a beating and the far right in ascendance, the only hope now lies in redirecting cultural and political theory as well as the study of liberal arts towards active politics. Pedagogy, therefore, has to turn into a radical struggle, provoking the academic world. Arendt was correct to note, as she did in her reflections of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, that ‘the tide of history can shift radically and rapidly, once established hierarchies are disrupted by the broad-based delegitimization of prevailing power relations.’