A mountain range has gone quiet. But when it did speak, almost a month ago, deep into a July night, in a thunderous voice that brought panic, death and despair, the nation was forced to listen; such was the ferocity of the landslide at Wayanad’s Vellarimala hills.

Scientists have cited a number of reasons to explain the disaster that claimed over 300 lives, most of them in the settlements of Mundakkai and Chooralmala. Altered climatic conditions that are leading to an intensification of rainfall, the decimation of forests, deleterious changes in land-use patterns in a zone vulnerable to landslides, aggressive cultivation, and poor drainage are among the causal reasons that have been cited.

Perhaps the most dramatic — and poignant — rationale was provided by a man — also a man of science. Explaining the ferocity and the scale of the disaster in Wayanad, K. Soman, a retired scientist and the former head of the Resources Analysis Division of the National Centre for Earth Science Studies, had this to say to a news portal: “The greatest losses [were] caused downstream from Vellarimala in Mundakkai and Chooralmala. In both places, the houses and buildings were situated on the river terrace… The river used to once course through these terraces and must have been diverted to its present course either by a previous landslide or due to reduced water. Water has memory, it remembers its course, even centuries after it was diverted.”

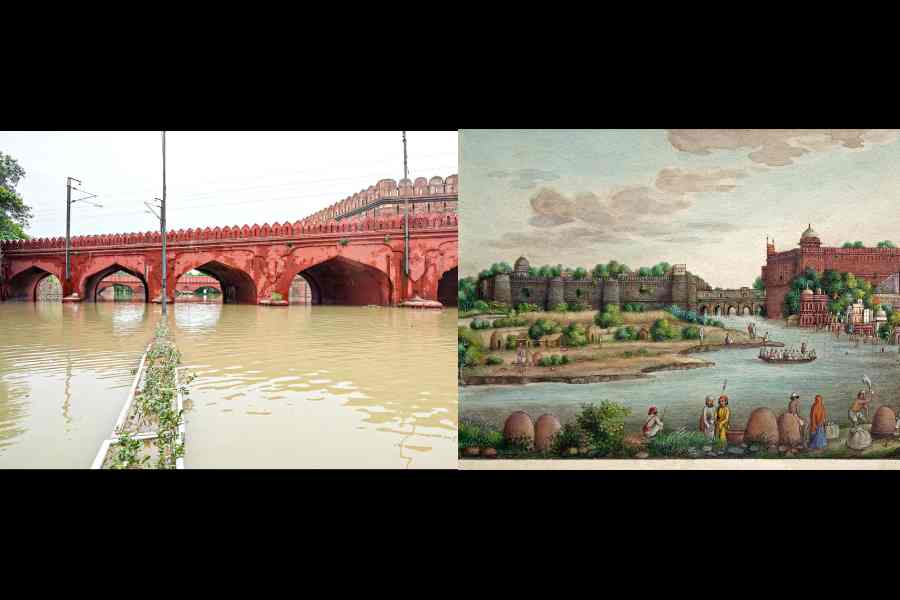

This hypothesis, of water retaining the ability to remember, is not novel. There are several instances of the public discourse resorting to such a proposition to explain unprecedented natural calamities. Thus, last year, when the Yamuna, ordinarily a frothy, polluted stream, breached its barriers to inundate, after years, the low-lying areas near the ramparts of the Red Fort, there was excited chatter, especially on social media, that the Yamuna had resurrected itself to reclaim territory that belongs to the river. Similar sentiments were heard when the Kosi devastated Bihar in the first decade of the new millennium. Incidentally, such conjectures transcend geography and national boundaries. Writing in a blog in 2020, John Mary Odoy, Climate Ambition Ambassador, Uganda, said that phenomena such as Lake Victoria flooding areas that it had once ceded on account of human intervention, Lake Kyoga flowing across its designated boundaries, or the mighty Nile and River Nyamwamba decimating habitation made sense if only one believed that water, Odoy writes poignantly, was, in a manner of speaking, returning home. Odoy was being echoed by the director of Colombia’s SINCHI Amazonic Institute of Scientific Research when she told journalists, after floods in 2018, that what was being described as the una avalancha — floods and landslides — was a chilling manifestation of rivers “expressing their memories”.

Science, of course, scoffs at the concept of vengeful, mnemonic waters. Yet, there have been attempts by scientists to prove the theory of water's memory that has some bearing on the field of homeopathy. In 1988, Jacques Benveniste, a French immunologist, published a paper in Nature supporting the conjecture of water’s ability to retain the memory of a substance that is dissolved in it. But the results achieved by Benveniste have never been replicated under controlled conditions, causing scientists to relegate the possibility of water possessing memory to the realm of pseudoscience.

What, then, explains the popularity of such a proposition — of riverine memory — in congregations separated by time and space?

One possible explanation could be that such beliefs are remnants of the debris of what are deemed as primitive knowledge systems that perceived the natural world as an organic extension of the human universe, practising, essentially, an original form of anthropomorphism. Little wonder then that anthropological research is rich in accounts of indigenous epistemological convictions about rivers being blessed with the ability to remember.

Perhaps it is the strength of this indigenous conviction regarding the avenging, vigilant river that is required, as opposed to scientific scepticism towards the memory of water, if we are to battle the many perils that confront river systems in India and the world. The increase in precipitation with the aggravation of climate change, in terms of spatial scale and intensity, is expected to raise the prospects of flooding across river basins in India. The dry months would bring a different, but equally portentous, challenge. Relevant data from the summer of 2024 compiled in an article in Down to Earth pointed out that the storage capacity of India’s major river basins has been declining continuously. This year, the Ganga basin, the largest in India, recorded water storage at less than half (41.2%) of its total capacity. The figures for some of the other prominent rivers were as follows: Narmada (46.2%), Tapi (56%), Godavari (34.76%), Mahanadi (49.53%) and Sabarmati (39.54%). The drying up of India’s rivers during summers that are set to get even more scorching and their transformation into agents of watery death during monsoons would have devastating impacts on lives, livelihood and food security.

India, across the ages, has attempted to deify its rivers. In recent times, the year, 2017, to be precise, the Uttarakhand High Court declared the Ganga and the Yamuna to be legal persons with specific rights. The judgment, it was hoped, would make it easier to frame legal deterrents to conserve the two rivers. Yet, the Ganga remains one of the most polluted rivers in the world with an estimated 600 kilometres of it declared an ecologically dead zone. The Yamuna suffers — daily— the injection of more than 800 million litres of largely untreated sewage along with the discharge of another 44 million litres of industrial effluents. Worryingly, India continues to be enthusiastic about its river interlinking project, aimed at transferring excess water from river basins with surplus water to the ones suffering shortages, despite serious environmental concerns about hydro-linking endeavours altering the cycle of monsoons, disrupting intricate hydro-meteorological systems, and, ironically, intensifying water scarcity across large swathes of land.

The failure of both divinity and law, in other words, the divine and the secular realms, to protect and revive river systems is one of the many examples of mankind’s fraying bond with the natural world reaching a point of inflection. This merits an urgent renegotiation on humanity’s part when it comes to its epistemic conception of natural entities. Merely bestowing natural elements with human characteristics to generate empathy — anthropomorphism at its most benign — is not enough. Rivers and mountains, flora and fauna, should be reimagined as aware, cognisant entities, capable of not only recollecting injustices inflicted upon them by human depredations but also avenging these humiliations by weaponising memory.

Science is likely to poke fun at this reasoning as reductive, romantic, or, worse, a return to a cruder, primitive (indigenous?) form of wisdom. But the worshippers of empiricism should remember that it is science’s capitulation at and complicity with rapacious, resilient economic and political systems — capitalism and neocolonialism — that have forced the raging waters to return home.

uddalak.mukherjee@abp.in