Another front opened up in the US-China confrontation this week when the Federal Bureau of Investigation arrested some people accused of operating a Chinese ‘secret police station’ in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Last month, Canada had initiated investigations into a few sites deemed to be similar Chinese outposts. China has always denied that it is involved in such activities. But it has been reported that around 100 such stations exist in more than 50 nations to ‘monitor’ the activities of Chinese nationals living abroad.

These developments come at a time when China is trying to project itself as a benign power interested in solving global problems. After years of facing a global pushback against its revisionist agenda, Beijing has become aware of the need to project a softer image. A window has opened up for China to make its presence felt anew as world leaders reach out to Beijing in a post-Covid era.

It has been an unusually hectic diplomatic calendar for Beijing. It has hosted several leaders, reached out to Europe and the Middle East, as well as presented itself as a peace-maker in the Ukraine conflict and the Saudi-Iran imbroglio. ‘Wolf warrior’ diplomacy has given way to a measured tone in global political outreach as China seeks to win friends and influence people at a time of flux. This Chinese attempt at global repositioning is rooted in its desire to present itself as a credible alternative to the United States of America. Whereas the Covid years saw China preoccupied with its domestic concerns, the post-Covid phase would necessarily demand that Beijing redress the situation by turning outwards.

This is also a time when there is a leadership vacuum in the global order. As geopolitical and geoeconomic crises escalate across the world amid a fundamental fracturing of major power relations, Beijing is seizing the moment to project itself as a global interlocutor. It also realises that if it doesn’t move fast, nations like India and leaders like Narendra Modi are also emerging as rallying points. India’s outreach to the developing world during Covid and its attempts to keep the ‘Global South’ at the core of its G20 presidency have challenged China’s self-perceived image as the leader of developing nations.

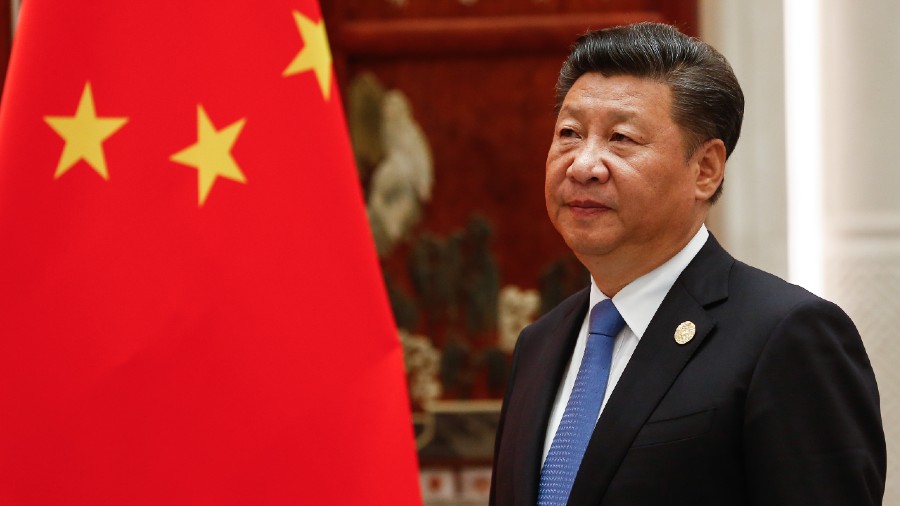

Xi Jinping and the Chinese communist party seem to be coming to terms with the reality that their hyper-aggressive foreign policy has left Beijing alienated and the costs of that are becoming untenable. China needs the West as it recovers from the Covid-induced economic slowdown to grow at a steady pace. As a result, China’s first major outreach after coming out of Covid isolation was towards Europe. In February, the diplomat and politician, Wang Yi, went to Europe to reaffirm China-Europe ties as well as to explore the possibility of weaning Europe away from the US. The Trans-Atlantic partnership has been unusually united in recent years in projecting a coherent China policy. For Beijing, it is critical to create fault lines in the West.

That wouldn’t have happened without a plan for Ukraine. So China released two position papers: a peace plan for the Ukraine war and a peace plan for the world, centred around themes of respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity as well as repudiating the use of unilateral sanctions. Given the Sino-Russian embrace leading to Xi Jinping’s visit to Moscow, the Ukrainian peace plan had very little to do with the war in Ukraine. But it was about underscoring Beijing’s credentials as a power that is serious about seeking some resolution to the crisis as opposed to the US that seems intent on prolonging the war.

For all of China’s efforts at being nice, Beijing has no real intention of backing down on its core demands as is reflected in its military intimidation of Taiwan and its aggravation in the East and South China Sea. The Sino-Indian boundary issue will also remain alive. China’s diplomatic rhetoric has become mellow. But its actions continue to shape the image of a power that is seeking its place in the international order by any means.

Harsh V. Pant is Professor of International Relations, King's College London