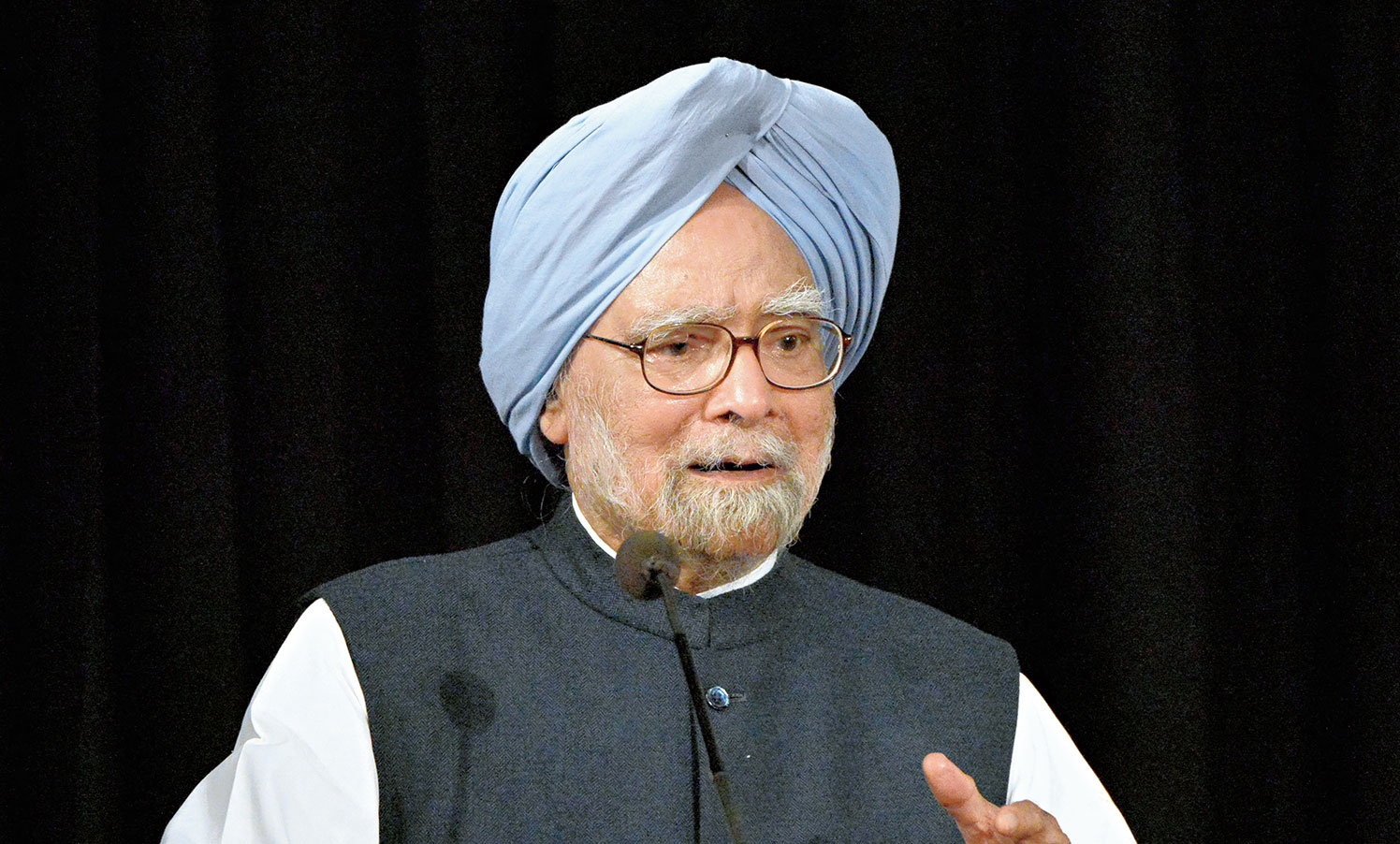

Manmohan Singh’s role in our history will, I hope, continue; but it already bears his imprint. He is the finance minister who led India out of the 1991 payments crisis; that was the last payments crisis we have had. One could say he was well rewarded for that service; he was prime minister for a decade. That was also the decade of the coal and telecommunications scandals, which singed his reputation — unfairly in his view: “I honestly believe that history will be kinder to me than the contemporary media,” is how he put it as he approached the end of his term. I have been a media writer since I left finance ministry in 1993, and have probably contributed unkind words from time to time. Media coverage is driven by current events and churned out with little time for reflection, so there is not much scope for it to be fair. Manmohan Singh’s time as prime minister also saw the highest growth rates recorded in India’s economic history since gross domestic product figures became available; it is worth remembering at a time when we are experiencing the lowest growth in a decade — since the global crisis of 2008. He is also the only Indian prime minister who is hero of a film — The Accidental Prime Minister — based on Sanjaya Baru’s book; it netted Rs 948500000. It may have made Sanjaya’s retirement comfortable, but I doubt if a penny of the royalty went to its hero. Still, it made him even more famous. So reconsideration is not entirely out of order.

The dual devaluation of the rupee in 1991 started a revolution in economic policy, and Manmohan Singh’s budget speech, which unveiled it, is justly regarded as its first step. It is now known that he was not the first choice; I.G. Patel was, but he refused to come back to Delhi from Baroda where he had retired. (Manmohan Singh jested that he has been called the accidental prime minister, but he may have been an accidental finance minister as well.) I had been writing in press in the 1980s about the idiocy of the economic policies of that time, and he wanted me to help him change them. It took him some time to take me into the finance ministry because Deepak Nayyar was chief economic adviser and there was a ban on new posts in government. But he managed to get a chief consultant’s post created with help from Montek Singh Ahluwalia; Deepak resigned in protest, I stepped into the CEA’s room, did his job for almost two years and worked together with Manmohan Singh on essential reforms.

But I had a lot more ideas for reforms — for ending the licence permit raj which the British created during World War II and independent India’s first rulers converted into a religion. Once the crisis was over, I found Manmohan Singh reluctant to do more reforms. P. Chidambaram, then commerce minister, was more receptive, active and enterprising; he implemented some of the reforms I suggested in 1991 when he became finance minister in 1997. Particularly important was the legalization of gold imports. They were banned during the Great War, and thanks to them, Dawood Ibrahim developed a lucrative business of buying dirhams from Indians working in Dubai, buying gold with the money in Switzerland, landing it in Dubai, loading it in fast boats and taking it to India’s western shore, bribing customs officials and selling the gold at four times its cost, delivering the Malayalis’ money to their wives in Kerala, and pocketing the rest. I told Manmohan Singh he should legalize gold imports; that would end the smuggling, and bring the remittances into the Reserve Bank of India’s coffers. He thought it too risky; Chidambaram did it in 1997 and destroyed Dawood’s business — until Arun Jaitley imposed import duty on gold and made smuggling profitable again. Eventually Manmohan Singh brought Montek into the finance ministry, and it was my turn to be kicked upstairs. Shankar Acharya was brought in as CEA in 1993, and I resigned. (From here onwards, I shall call Manmohan Singh M1, and Montek Singh M2.)

That story is missing in M2’s just published memoirs, Backstage; he has also been a bit economical on the role of other reformers, especially Chidambaram. But otherwise it is a good account of the reforms — after M2 was transferred to the finance ministry. He suggests that the reforms began with the M document, a brief he gave the former prime minister, Vishwanath Pratap Singh, in 1990; they had gone to Malaysia, V.P. Singh was impressed by Malaysia’s progress and asked M2 to tell him why it had done so well. The document leaked out; it was not known who wrote it, but seeing the views and style, I ascribed it to M2 and called it the M document in The Indian Express. Chandra Shekhar became prime minister in November 1990, and made M2 commerce secretary, where he stayed until M1 captured him, and then remained finance secretary till the Bharatiya Janata Party government moved him to the Planning Commission. M1 elevated him to its deputy chairmanship after he became prime minister in 2004; M2 resigned in 2014 when the BJP won the general election, and took time to write memoirs.

M2’s story is as much about M1 — who is a reticent man — as himself. We are unlikely to get an autobiography from M1. The nearest we will come to it is his daughter Daman’s memoirs, Strictly Personal: Manmohan and Gursharan. M1 seems a Sphinx-like figure; Daman makes him come alive, from being scuttled from one branch to another of a rural joint family in childhood, topping examinations despite a poor education, and rising from a nameless village school to Cambridge and Oxford, to ascend from chief economic adviser to prime minister.

She cannot know about M1’s political and official roles played behind closed doors; M2’s narrative comes in here. He covers the scandals under M1 as prime minister — the telecom scam, the coal scam, Commonwealth games and so on. They have created an impression that M1 was honest but did not prevent corrupt ministers from pursuing their business; M2 tries to correct it. There is a limit to what M2 can do: the scams did occur and were not stopped in time. The prime minister did not necessarily know in time to prevent them; any moderately clever scamster would have kept them hidden from him. Maybe he knew, but higher compulsions — for instance, keeping the United Progressive Alliance in power — prevented him from stopping them. Maybe he tried but failed. There is much he did that is not public; only he can tell us. He is gradually becoming more communicative; if he can tell Daman such colourful stories about his life, he can reveal some to us too. He should act in a film about himself; it will be a blockbuster. But he may well stick to his habit of keeping secrets of his choice. In which case, he should write Urdu nazms; he will be at least as good at it as at being prime minister, and it will make him famous in his land of birth as well as his playing field.