Montek Singh Ahluwalia, who served as deputy chairman of the now-defunct Planning Commission, has said that then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh had asked him whether he should resign after Rahul Gandhi trashed an ordinance the ruling UPA had brought in 2013 to negate a Supreme Court verdict on convicted lawmakers.

Ahluwalia says he told Singh, then on a visit abroad, that he did not think a resignation would be appropriate.

The former civil servant’s recollections came in his new book, Backstage: The Story behind India’s High Growth Years.

The Congress-led UPA government had brought the ordinance to provide immunity to members of Parliament and legislative Assemblies from immediate disqualification, overriding a Supreme Court judgment on the issue.

The cabinet had cleared the ordinance but Rahul, in a major embarrassment to his own government, had denounced it as “complete nonsense” and said it should be “torn up and thrown away”.

Singh, while returning home from the US, appeared piqued over the entire episode.

“I was part of the PM’s delegation in New York and my brother Sanjeev, who had retired from the IAS, telephoned to say he had written a piece that was very critical of the PM. He had emailed it to me and said he hoped I didn’t find it embarrassing,” Ahluwalia recalls.

The article was widely reported with reference to the author being Ahluwalia’s brother. “The first thing I did was to take the text across to the PM’s suite because I wanted him to hear about it first from me. He read it in silence and, at first, made no comment. Then, he suddenly asked me whether I thought he should resign,” Ahluwalia writes in his book.

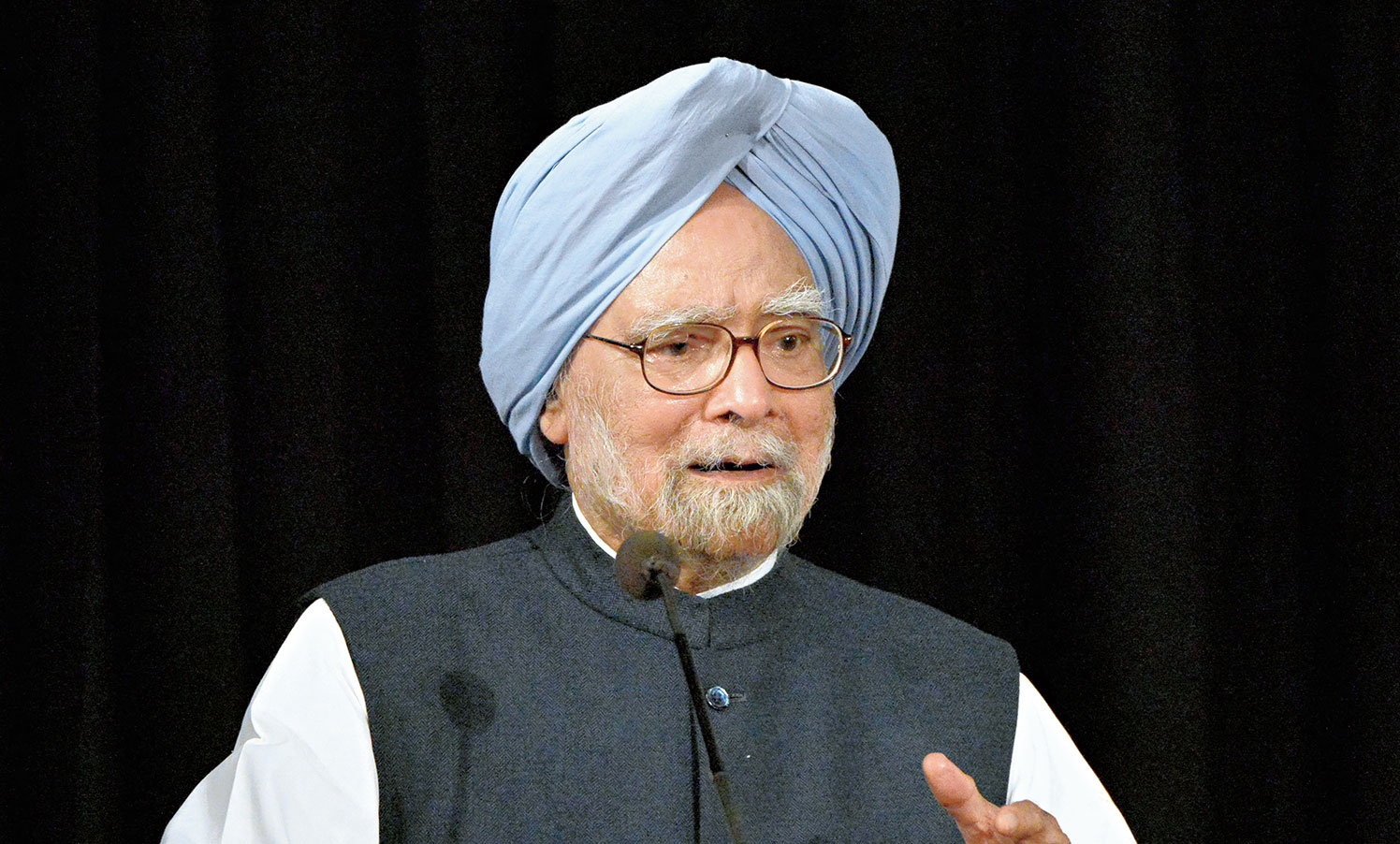

Montek Singh Ahluwalia Telegraph file picture

“I thought about it for a while and said I did not think a resignation on this issue was appropriate. I wondered then whether I was simply saying what I thought he would like to hear but on reflection I am convinced I gave him honest advice,” Ahluwalia says.

“Most of my friends agreed with Sanjeev. They felt the PM had for too long accepted the constraints under which he had to operate and this had tarnished his reputation. The rubbishing of the ordinance was seen as demeaning the office of the PM and justified resigning on principle. I did not agree,” Ahluwalia writes.

He argues that the incident highlighted a fault line in the UPA. “The Congress saw Rahul as the natural leader of the party and wanted him to take a larger role. In this situation, as soon as Rahul expressed his opposition to the ordinance, senior Congress politicians, who had earlier supported the proposed ordinance in the Cabinet and even defended it publicly, promptly changed their position.”

Rahul, who was then the Congress vice-president, had called on Singh when the Prime Minister returned. He also made it clear he was not undermining Singh’s authority in any way.

Ahluwalia calls his book, published by Rupa, a travelogue of India’s journey of economic reforms “in which I had the privilege of being an insider for 30 long years”.

The former bureaucrat, who played a key role in the transformation of India from a state-run to a market-based economy, presents the story behind the country’s economic growth in the first half of the UPA’s tenure. He also discusses the successes and failures of the UPA regime, a period he served as deputy chairman of the Planning Commission.