Even a brief visit to Goa is a revelation. Most striking of all is just how much of a destination it has become for the upper middle class and the wealthy from across the country, especially those from Delhi and the National Capital Region.

Through the 1950s, the residual decolonisation of Pondicherry and Goa had a primacy in public and political narratives that is difficult to imagine today. The French were pragmatic with regard to Pondicherry and the other smaller enclaves in their possession — even out of character, given the violence that took place in Algeria and Indo-China through the 1950s as the French resisted any effort to evict them with surprising military intensity. But by 1955, the merger of the French possessions with India had been satisfactorily settled.

Goa was a different case, however, in large part because of the ruling regime in Portugal and, in particular, António de Oliveira Salazar, its long-serving prime minister but, in effect, its dictator. Negotiations were attempted in the early 1950s — the Indian expectation quite reasonably being that the Portuguese would see the writing on the wall and the absurdity of maintaining an enclave in a nationalistically-charged India. This was not to be. To Salazar, Goa was not a colony but a province of Portugal so the question of leaving or of decolonisation did not arise.

In an article in the prestigious American journal, Foreign Affairs, he was to write in 1956, “No qualified traveller passing into Goa from the Indian Union can fail to gain the impression that he is entering an entirely different land. The way people think, feel and act is European.” Goa, therefore, was to Salazar, although he had never visited it, “[T]he transplantation of the West onto Eastern lands, the expression of Portugal in India.”

Incidentally, in what is an interesting aside on the current India versus Bharat debate, to Salazar, the fact that the Congress chose to name the new country ‘India’ rather than ‘Hindustan’ was a diabolical move because of its ambition to be “considered as the legal inheritor of the contractual obligations of undivided India.” Salazar argued further that with the partition of British India in 1947 and the earlier transition to sovereignty in Ceylon and Burma, there could be no basis to the Union of India claiming, after 1947, to represent pre-1947 India as a “geographical expression”. Thus, he argued, to cede to its claim to Goa would be to “undermine the very basis of the independent existence of Pakistan, if not of Ceylon and Burma.”

In the face of such obduracy, progress clearly was not possible. When other pressures, including an economic blockade, did not work, the stage was set for a military intervention to evict the Portuguese in December 1961. To many, the question now is why did the entire process take so long? Jawaharlal Nehru’s procrastination is usually faulted these days. There were, however, real pressures, not least from the Western bloc as a whole and from the United States of America, in particular. It can also be reasonably argued that Goa was a relatively small matter given the scale then of India’s vast challenges. Finally, there was the argument against military means given India’s own non-violent struggle against British imperialism.

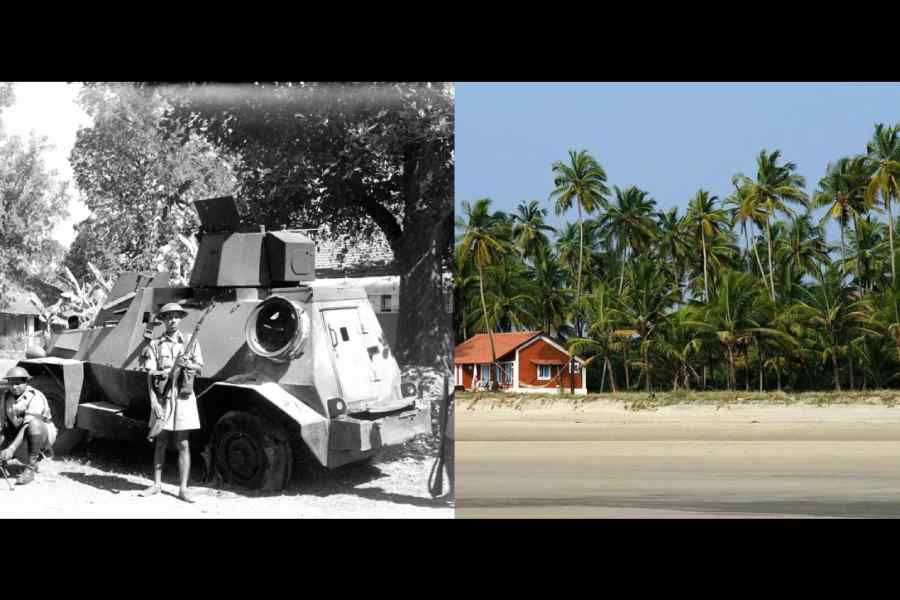

So what tilted the balance? There were pressures on the government from its political Left and Right fuelling public impatience that matters had dragged on for too long. There was also mounting criticism of and a great deal of expectation from leaders of liberation movements in the Portuguese colonies in Africa. Perhaps political calculations of a different order were also at play — the next general elections were a few months away and V.K. Krishna Menon, the then defence minister, faced a difficult contest in Bombay. In the event the military action was a quick success — if for no other reason than the fact that the Portuguese never had readied a military option to defend Goa.

As the Portuguese in Goa surrendered, the reactions across the world were divided, as was to be expected. The West was disapproving, even condemnatory; the newly-independent colonies were supportive and the Soviet Union vetoed a UNSC resolution that India withdraw its forces. The adverse reactions could be managed relatively easily in part because there was no great sympathy for Portugal’s obduracy even in the Western camp. The domestic reactions were — again to be expected — triumphal and euphoric.

The military operation also did reduce domestic pressure on the government, which was facing real difficulties with China on the border from 1959 onwards as well as criticism from the public and the political classes for being too soft and always on the defensive. If putting down a lesser foe effectively deflected such criticism and inflated our self-esteem, hubris would inevitably strike back and within a year there was a massive Chinese aggression in NEFA and in Ladakh. If there is a lesson to be drawn from times past that certainly is one: excessive pride and triumphalism always take a fall.

But to return to the influx of the wealthy into Goa today, what is evident is that this is more than tourism. Apartment complexes, stylish bungalows and luxurious villas are as, if not more, prominent as resorts or hotels and suggest much more than short-term visitors seeking the sand and beaches of the Arabian sea. Perhaps it is the sharp deterioration in North India’s air quality and the acceptance that it is now going to be a structural feature of daily life. Perhaps another reason were the long lockdowns of 2020-22 that left as their legacy the knowledge that you can work from just about anywhere as long as connectivity is good and there is a good airport nearby. But most of all, it could just be the more cosmopolitan environment, its salubrious climate, and a flavour of something different that beckons. It is, of course, also ironic that Goa’s Mediterranean character — Salazar’s “the expression of Portugal in India” — should now make it such an attractive location to live in for so many from across the country.

T.C.A. Raghavan is a former High Commissioner to Singapore and Pakistan