Legend has it that the pride of Lucknow — Hazratganj — was inspired by Calcutta’s Chowringhee. Saadat Ali Khan, who was the half-brother of the nawab of Awadh, had fled to the city on the banks of the Hooghly in 1775 to avoid a murder charge, and been welcomed there by the conniving East India Company. During his 20-year stay in Calcutta, Saadat, apart from acquiring a western lifestyle, developed a love for its architecture, much of it inspired by Greek and Roman styles.

So, when in 1798, the Company succeeded in anointing Saadat as the fifth nawab of Awadh, he was horrified by the narrow and filthy roads of its capital, Lucknow. He decided immediately to build a road as grand as Calcutta’s Chowringhee. And so a wide promenade, named Hazratganj in later years, was constructed to join Dilkhusha — a European-style building with stables and a deer park — to the Residency where Englishmen lived.

The new, handsome road was compared with high streets in England by contemporary Englishmen. It had impressive gates at either end and sprawling estates, with stucco white mansions, fronting it. Saadat’s pride found resonance with his subjects; and, down the centuries, Lucknowis have been proud of this legacy, even though it has witnessed many a historical upheaval, not the least being the spiteful demolition of many of its buildings after the 1857 rebellion.

Over the years, Hazratganj changed character with residential estates giving way to stylish commercial establishments. During the British Raj, it became a hub of entertainment and upmarket shopping — ballrooms and tea-places, libraries and plush cinema halls, smart tailoring outlets and Chinese shoe shops sprang up where estates once stood. In the pre and post-Independence era, coffee houses appeared where politics and poetry were discussed in equal measure. In keeping with the city’s academic credentials, bookshops mushroomed as well.

Some of my memorable years as a teenager, in the late 1960s, were spent in this city of erstwhile nawabs, with “Ganjing” being the weekend pleasure that my cousins and I indulged in. “Ganjing” meant dressing up modishly to take a stroll down Hazratganj with other stylishly-attired youngsters and smart, young army officers in their civilian best. Life moved at a lei-surely pace and Hazratganj epitomised it.

Saadat Ali Khan’s road turned 200 in 2011. To celebrate its glorious history, its occupants joined hands with the authorities to give the road a facelift. Among other things, ugly hoardings were removed, a uniformity of shop frontage was put in place, and street lights and furniture in wrought iron and wood were installed.

In recent years, when the rest of Lucknow got lacerated with Metro lines, the skyline of Hazratganj was spared. City planners dug deep and took the line underground through the major stretch of their stylish road, to preserve the beauty.

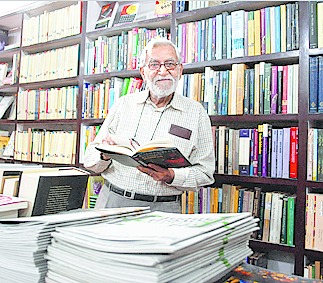

Unfortunately, several of Hazratganj’s iconic institutions have died quiet deaths, unable to keep pace with changing times. Cinema halls closed down one after the other, including the 1939-built Mayfair, which screened Hollywood films. The Mayfair building also housed the British Council library, Kwality’s, where we lingered over cold coffee and almond biscuits, and a bookshop run by a prominent citizen of this road, Ram Advani. Mayfair building today stands silent and forlorn.

Though “Ganjing” is no longer what it was, one thing I have found constant is the syncretic culture of the avenue. Symbols of Islamic, Hindu and Catholic religions co-exist here harmoniously, unaffected by the cacophony of political troublemakers. Also, though hooliganism may be increasing in other parts of the state, tehzeeb continues to be the leitmotif here. Shopping here is, therefore, still a pleasant pastime. For instance, the helpful proprietors of

Universal Booksellers make you feel very special by pretending to recall you from earlier visits, while their staff spoils you for choice by digging out half a dozen titles of the author you are looking for. And coffee shops let you spend hours catching up with old friends and traffic police help you cross the road without being run over by speeding vehicles.

So, when on a chilly January 26 this year, I stood on the sidewalk of Hazratganj with other citizens to watch the Republic Day parade go by, I couldn’t help my heart swelling with pride, not dissimilar to that of the fifth nawab of Awadh, and my eyes getting moist with patriotic fervour.