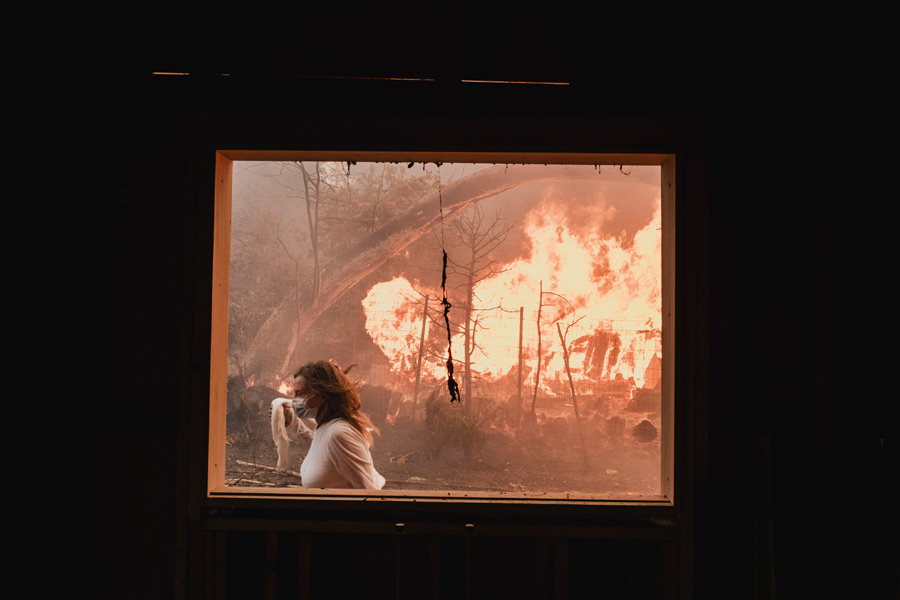

Home is where the heart is, or so goes the adage. But the human heart did not always crave a still hearth. In fact, before the emergence of agrarian societies, the early humans journeyed along the roads taken by their prey — hunter-gatherer societies were mobile and the road was their life. But with the rise of agrarianism, humans learnt to put down their roots and a life of journeys became something to be frowned upon. Yet, vestiges of the wandering spirit persist. In the year, 2000, Herman and Candelaria Zapp set out in a car from Buenos Aires to travel the world. The Zapps’ home is the road — literally and proverbially. They have had four children in different countries, and in an era of strict visa regimes and rising insularity, managed to treat borders as what they truly are — arbitrary and artificial lines on a map. The world was a different place when the Zapps set out — there were no smartphones, the internet was in its infancy, a site of knowledge and hope rather than disinformation and division, the twin towers towered over New York, and Russia was a diminutive shell stripped of its Soviet grandeur. It is tempting to imagine that the Zapps hummed Kishore Kumar’s immortal song, “Musafir hoon yaaron, na ghar hai na thikana”, as they covered great distances across a changing world.

The Zapps, interestingly, are not an anomaly. Latest estimates show that over one million Americans live permanently in recreational vehicles with no permanent address. Many are retired, but many others work part of the year, just long enough to keep them going for a few months or so. It is easy to romanticize the lifestyle and the idea of freedom that it brings. But in most countries, people without a stationary home are subjected to intense legal scrutiny. Law enforcement institutions are even prejudiced against specific communities. For example, in the United States of America, there are legislations that make it illegal to sit on the sidewalk, to camp or sleep anywhere in a downtown area or to hang around in a public place without an apparent purpose. The intent seems to encourage sanitization of space of some kinds of human presences. These laws are not unique to the US. Anti-vagrancy laws have existed for hundreds of years — think of the persecution of gypsies across Europe. In the old United Kingdom, vagrants could be put in jail, sold as slaves, or sometimes even killed for no other reason than wandering. Colonial India, too, had witnessed the purge of nomadic communities, most notably under the guise of the campaign against thuggees.

But the road is retaliating along with the rise of liberalism. There are now movements across Europe and the US fighting for squatters’ rights to be made universal. They claim that housing and shelter — especially abandoned spaces — should be used by those who require it. This is not to suggest that the nomadic lifestyle is a universal choice. Penury, drug abuse, domestic strife, trafficking and so on force people out onto the street. Yet, the attraction for the road — for liberation — proves that the project to idealize domesticity may be resisted by some.