To be imbued and attuned to the shabad; to be kind and compassionate; to sing the kirtan — these are the most worthwhile actions in this Dark Age of Kali Yuga

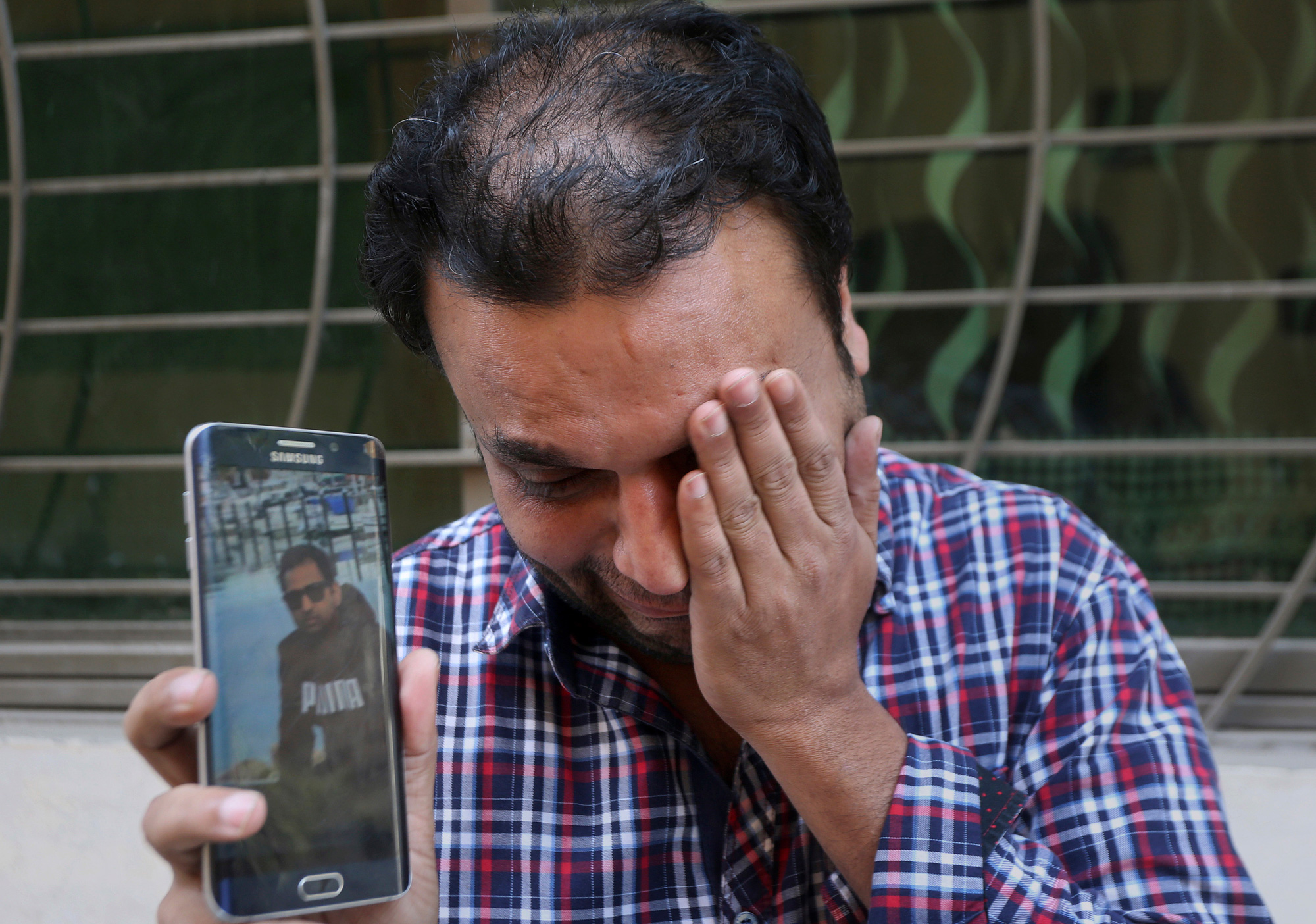

In the darkness of death, New Zealand’s Sikh population has brought this shabad to life. For Christchurch’s tourniquet of pain, balm came from “Guru Nanak’s Free Kitchen, Auckland' and Young Sikh Professionals Network NZ with the speed of light. Not just in the traditional form of opening a langar for those arriving at the venue to help, but in another basic, immediate and most cathartic of needs. The many dead in Christchurch needed obsequies. And all at the same time. In coming forward to move the bodies to the cemetery, washing them and readying them for burial, the Sikh community became to the Muslim slain, next of kin.

The community spokesperson, Daljit Singh, said: “The Sikh community stands strongly and firmly with the Muslims because this act of terrorism happened in a place of worship, and we will spare no effort in supporting them.” Asking gurdwaras to support New Zealand’s Muslim community in the gurdwaras’ respective regions, the Young Sikh Professionals proceeded to issue a statement. It is a model in phrasing for any spokesperson of government anywhere: “This kind of violence and the hate it perpetuates has no place in any country and we have a collective responsibility to stand up and say no — this is not us. We are reminded of the tragedies at Pittsburgh, Oak Creek and Charleston that were driven similarly by racial, religious and ethnic hatred and urge our community, and in particular our elected officials, to denounce this attack in the strongest possible terms.” They would have filled Gandhi and Netaji with hope.

When the Sikhs of New Zealand said of the Christchurch carnage “This is not us”, they were paraphrasing their prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, who said the terrorist was “not us”, immediately after saying of the slain, “They are us.” She spoke not just nobly but transformatively.

The reflexive activation of the core of their faith as enunciated by Guru Nanak in the Guru Granth Sahib had another feature: the offering of votive space to Muslims to undertake namaz in gurdwaras. For sheer originality and sublimity, this gesture was unique, redemptive. And there it holds, quite unintendedly but unquestionably, a great lesson for India locked in the mandir-masjid issue around Ayodhya.

No greater example in creative mediation can be found than in this for the three eminent gentlemen who are now tasked with mediating in the Ayodhya matter.

But to return to Sikhs and Sikhism.

Social media redeemed its abysmal image and reputation in the ensuing flow of tweets. One from a Sikh lady said: “The Sikh community’s response is moving me to tears.” Another from a Sikh gentleman: “This is what it means to be a Sikh.” A Maharashtrian gentleman tweeted: “Salute to you and to all Sikhs!” And crowning all tweets, from a sensitive soul by the name of Emily Cragg: “Will Sikhs civilize the rest of the world? Possibly... Hugs to you all.”

Reading these tweets, two images came to mind. The first was of a tall Sikh, Colonel Niranjan Singh Gill of the Indian National Army, and of Colonel Jivan Singh, also of the INA, who volunteered with other INA soldiers to go to Noakhali, in 1946, to help quell communal riots. The Sikh-led INA group was not large but it was right there, beside Gandhi, during the most intense crisis. Pyarelal writes in his biography of Gandhi (The Last Phase, Part II): “The I.N.A. had built up a fine tradition of bravery and patriotism under the leadership of Netaji Subhas Bose. They had banished communalism wholly from their midst whilst they were under colours. ‘We had worked in the Indian National Army,’ ran one of their manifestos, ‘and we are happy to be able to say that we had forgotten all distinctions of caste, creed or Province. It was Jai Hind for all of us. The memory of those days still persists.’ Before their final surrender, Netaji had told them by way of parting advice that on their return to India, they would have to convert themselves into soldiers of non-violence and take their orders from Gandhiji.”

This cameo was of Sikhs at the line of fire, quelling it. The second was of Sikhs again at the line of fire but receiving it. It comes from New Delhi, November 1, 1984 and is of five Sikhs, including two famed for their heroism in war — the country’s only Marshal of the Indian air force, Arjan Singh, and Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora, the hero of 1971. The other three were the writer, Patwant Singh, the distinguished diplomat, Gurbachan Singh, and Brigadier (retired) Sukhjit Singh. Shocked into disbelief by the carnage and rapine let loose on Delhi’s Sikh population after the assassination of Indira Gandhi, the benumbed but determined group first called on the then president, Giani Zail Singh, who was agonized but immobile. Then on the then home minister, P.V. Narasimha Rao. “The Army will be called this evening,” the home minister told the group. Lt Gen Aurora asked, “How will it be deployed?” The minister said, “The Area commander will meet the Lt Governor for this purpose.” Aurora responded grimly, “You have called the Army 30 hours too late.” A wound of incalculable pain was inflicted on Sikh India.

Not until the former prime minister, Manmohan Singh, in an act as courageous as it was conscientious, apologized from the floor of Parliament for 1984 was the wound suffered by Sikhs in 1984 addressed. Real healing would have come if, overcoming his personal bereavement, the just-inducted prime minister then, Rajiv Gandhi, had stepped out, gone to Trilokpuri, Jahangirpuri and other affected sites, embraced and addressed the victims as Jacinda Ardern did in Christchurch and, putting the fear of god in the murderers and rapists, assuaged the Sikh community. He must have wanted to do that, but was held back by political advisers.

Sikhs, in a place as far from home as Christchurch is from Chandigarh, have brought, with reflexive, imaginative, sublimity, the great shabad on compassion to light and life. Becoming, in Pyarelal’s memorable phrase, ‘soldiers of non-violence’, the Sikhs of New Zealand have created a history of sorts and we must salute them.

Historical veracity requires any narrative on the Sikhs to acknowledge that in the record of communal violence during the partitioning of India, in 1947, Sikh India is not unstained. Likewise, the world’s annals of terrorist violence include acts in the 1970s and 1980s, of those Sikhs who did not scruple to assassinate political adversaries, including security forces on duty and innocents. Caste discrimination has not been purged by Sikh India.

And yet, there is that ‘something’ in the Sikh persona, illumined by the shabad and by its ten Gurus that, these painful and self-condemning transgressions notwithstanding, it continues to stand tall.

In a letter to Mahadev Desai written on January 4, 1936, Rabindranath Tagore said: “Sikhism has a brave message to the people and it has a noble record. How great would be its effect, if this religion is to get out of its geographical provincialism, shed its exclusiveness inevitable in a small community...”

Away from all geographical provincialism, New Zealand’s 20,000 Sikhs and their 13 gurdwaras would have made Tagore proud.

But, though reported in Indian media, this example of humanity, of courageous steadfast compassion, has been lost on us.

Why?

No deep introspection is required to answer that question.

We are practising the opposite of “They are us”. We are getting used to “They are they, we are we”. We are getting drilled, slowly but steadily, into ever wanting victory, triumph. Success is seen only in the Other’s defeat, accomplishment in the Other’s failure. Peace is pious, victory exciting. Reconciliation is found in dead texts, revenge in living media. Three Vs drive us now: Vengeance, Vanquishing, Victory. Manava rasa guided human help to victims of the massacre. But the rasa of our times in India is vira rasa.

And yet, somewhere, a vein of hope keeps a feeble pulse going — a miracle. And for that, again, we have Guru Nanak to thank. Pulwama terror and Balakot notwithstanding, India and Pakistan have kept bilateral talks on the Kartarpur corridor on track.

Lifelines can be slender. But they retrieve life from death. In this Kali Yuga, the light of the shabad referred to at the head of this article, working at Christchurch and Kartarpur, must do that.

Waheguru Ji ka Khalsa

Waheguru Ji ki Fateh.