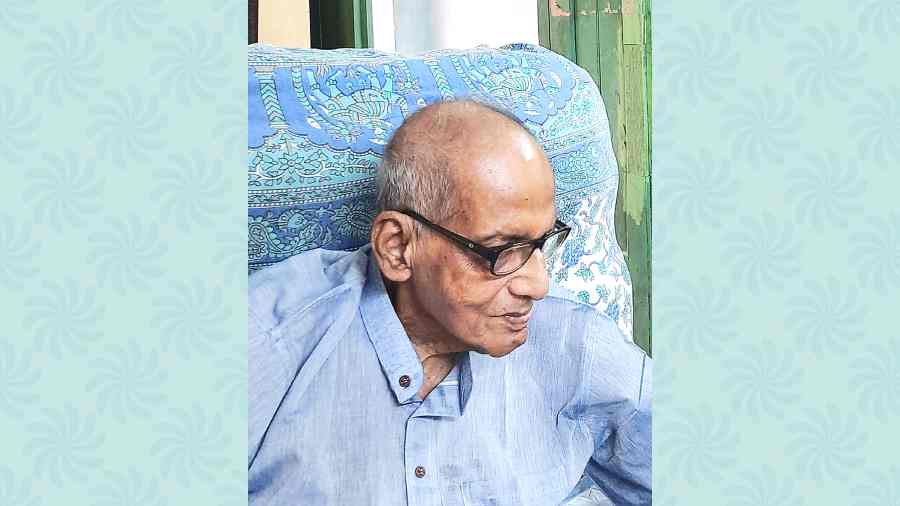

My old teacher Arun Kumar Das Gupta turned ninety last month. I went to see him on the occasion. There were several celebrated teachers of English at Calcutta’s Presidency College in the 1960s. ‘AKDG’ had the rarest turn of intellect among them all. It was largely from him that a generation of future academics acquired not only a factual but a conceptual grasp of some crucial developments in human thought. At that time, such matters were not commonly studied in English departments anywhere in the world. However inadequately, some of us have tried to convey those ideas through our own teaching and writing. Always reclusive and now housebound, this scholar of the shadows has left an unsuspected legacy to generations of students and researchers.

In good part, such scholars remained in the shadows because they chose to stay there. If there is one charge we can fitly lay at their door, it is that they wrote little to perpetuate their scholarship. They set themselves dauntingly high standards that a lifetime would hardly suffice to reach. When Amal Bhattacharji finally felt he could write ‘as a convinced man’, cancer claimed him within a year. Also, they combined a genuine indifference to praise or recognition with a fastidious shrinking from the outer world. This made (at least in the finest minds) for an admirably unworldly commitment to pure scholarship, unmoved by any thought of acclaim or reward. I am mortified when I compare the external compulsions driving my own generation and the next. But it also meant that those elders left little direct impact on later generations or on the wider academic community.

There is another factor. As a government institution, Presidency College remained a colonial entity into the twenty-first century. (It may have changed in its new avatar as a university: let others tell that story.) Like H.M. Percival and Praphullachandra Ghosh in British times, Taraknath Sen and Arun Das Gupta in independent India could not consolidate their classroom teaching in a full-fledged research department addressing the discipline in its totality. Taraknath Sen did try, but despaired after exhausting tussles with officialdom.

This is the story of virtually all Arts and many Science departments at Presidency. The college was propelled towards implosion by the bureaucracy entrusted with nurturing it. The Naxalite movement and the Left Front’s belligerence (the latter operating through the bureaucracy) were incidental factors.

Hence ironically, the college failed to profit from a new, post-independence educational bureaucracy. For all its failings, the University Grants Commission supported a nationwide network of public universities on inclusive lines.

In Bengal too, institutions with greater freedom of operation seized the opportunity. Incredibly, the state government’s education department never engaged sustainedly with the UGC to benefit either Presidency or the college network generally. At most it forwarded self-motivated proposals from individual departments. Nor did it allow academics to function on their own.

Disempowerment is the price extracted by society for the (often notional and exploitative) respect it affords its teachers and scholars. They suffer from a crippling lack of agency. As a novice teacher at Presidency, I found my seniors either fighting the system or, more commonly, in surrender to it. Some, like Arunbabu himself, had to leave the college to ensure dignity and security in their own lives.

Nineteen years on the Presidency faculty make me view the college differently from those who passed through it as students. Their nostalgia can be unclouded: the first flush of intellectual excitement, inseparable from their first encounter with the world outside school and home, the first taste of growing up. My memories relate to a sadder and wiser adulthood. There was stimulation in plenty, from colleagues like Arunbabu or the wise textual scholar Sailendrakumar Sen; also from pupils like the late Swapan Chakravorty. But for all that enrichment, my legacy from Presidency is weighed down with too much emptiness — the baggage of the unfulfilled, of what the institution might have been.

It may be premature to say the same of the entire public university system. But the Indian government is perceptibly disinvesting in the nation’s higher education. The market-led system willy-nilly replacing it sees education as a personal rather than a social good. Most Indians can neither buy nor sell in that market.

The old State-run degree factories had the merit of being cheap. They made room for everyone, including the talented, from all across society. Being undemanding, they could harbour innovative, even idiosyncratic, scholars within their ecosystem. If by luck or good management, a university housed many such intellects (who in turn attracted more), it could bring the curriculum to life and foster adventures in research.

Most private institutions confine their teaching to a few standard lucrative courses undemandingly taught and effectively shun research. (There are notable exceptions.) The phrase ‘knowledge economy’ has been infantilised to mean running schools and universities for profit. In such an economy, persons ‘merely’ advancing learning might starve. Yet so might many products of this pragmatic system: contrary to naïve calculations, no economy can flourish on a drip-fed diet of ‘practical’ knowledge.

That is why humanist scholars like Arun Das Gupta must be viewed with something more than empty piety and nostalgia. Education has its own ecosystem, hence its own economy even in financial terms. In that economy, the freewheeling pursuit of knowledge cannot be divorced from its material returns, nor the latter from broader human welfare. The United States of America, that consummate knowledge economy, amply admits the first point while struggling with the second. It is commonly granted that technology cannot be divorced from the basic sciences. But we would still shrug off the lessons of the social and human sciences that inequality, thought control and narrow self-interest cannot be to anybody’s benefit. I say nothing of more abstruse theoretical inputs organic to all knowledge.

When I visited my old teacher, his eyes lit up with the familiar sparkle when we talked about books. Had he asked after the state of education, I could not have looked him in the eye.

Sukanta Chaudhuri is Professor Emeritus, Jadavpur University