Kerala’s Syrian Christians solemnly observe the first week of September as the Eight Day Lent of Mary in remembrance of the birth of St Mary, mother of Jesus. During this week, they involve themselves in only noble activities — fasting, praying, participating in charitable and evangelical activities. But this September, a sermon delivered by the venerable bishop, Joseph Kallarangatt, of the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, concluding the holy week, has led to a virulent communal frenzy in Kerala even as the state is reeling under the coronavirus. At a church in Christian-dominated Kottayam district, the bishop of SMC’s Palai Diocese warned the faithful to be beware of the diabolical “narcotic jihad” indulged in by some Muslims to entrap Christian youth into drug addiction.

A month earlier, on the centenary of the historic Malabar Rebellion (also called the Moplah Revolt) at Kozhikode, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh leader, Ram Madhav, said that the revolt was the first manifestation of the Taliban mindset of Muslims in the country in the 20th century. This has coincided with the Indian Council of Historical Research’s reported move to expunge the names of 387 persons who were killed in the rebellion from its “Dictionary of Martyrs of India’s Freedom Struggle”. Two years ago, a project to make a biopic on a leader of the rebellion was fiercely opposed by the Hindutva camp across the country. The project has since been shelved.

Both these remarks appear to have beleaguered Kerala’s Muslims with Christians and Hindus arrayed on the other side. They have vitiated Kerala’s atmosphere, traditionally known for its communal harmony, with polarizing calls to boycott Muslim establishments or even cabs driven by them. Yet, saner voices are also being heard from all communities opposing them, with even four young nuns walking out of a church mass when a priest repeated the bishop’s charges. Both the ruling Left Democratic Front and the Opposition, the United Democratic Front, have condemned the attempts to divide but dithered on taking a firm position fearing backlash from the communities. The Bharatiya Janata Party, which has been trying to woo Christians, has defended Christians and pleaded the Central government to intervene. Even as it opposed blaming the Muslim community, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) has said there were attempts to woo women by terrorist groups on campuses. It alleged that extremists were trying to grow among minorities by making use of growing Hindu fundamentalism. Leaders of the Congress and the CPI(M) have visited leaders of both communities, ostensibly to pacify. The statement by the chief minister, Pinarayi Vijayan, that the bishop’s remark, though unwarranted, was not ill-intended has kicked up more dust. Following widespread criticism, Vijayan took a firmer stand, slamming the bishop’s use of “narcotic jihad” that puts the blame for social evil on a community.

The bishop’s charge has come on the heels of many anti-Muslim moves made by the SMC, which leads Kerala’s largest Catholic community. It forms 62.6 per cent of Kerala’s Christians who constitute 18.38 per cent of the population. SMC had earlier raised the ‘love jihad’ charge, accusing Muslims of luring Christian girls by feigning love and marrying them, leading to terrorist activities. Although the police and courts later found the charge to be baseless, the SMC kept citing the presence of a Christian and a Hindu woman among those who went to Afghanistan with their spouses to join the Islamic State in 2016. The 2010 incident of chopping off a Christian college professor’s palm by Islamists, who accused him of blasphemy, had gravely ruptured the trust between the two communities. However, Professor T.J. Joseph later said that he was hurt more by the Church as it had him dismissed from college even after the attack, accusing him of causing communal disturbances. The consequent trauma led to his wife committing suicide.

Ironically, the present war between Kerala’s Catholics and Muslims coincided with unprecedented moves by the supremo of Roman Catholics, Pope Francis, to bring them together globally. Reasons for Christians’ ire against Muslims run deeper than what meets the eye. It rises from the way power equations in Kerala society have altered in recent decades. The ongoing Muslim advances spurred by the Gulf migration and remittances have threatened the long-held, preeminent position of Syrian Christians in many fields like business, education, politics and so on. They are most alarmed by the recent demographic shift in Kerala under which Muslims have replaced Christians as Kerala’s second-largest community. During 1951-2011, Hindus’ share in the population fell from 61.6 to 54.9 per cent, Christians from 20.9 per cent to 18.44 per cent, while that of Muslims rose from 17.5 to 26.6 per cent. According to a study by the Centre for Development Studies, Hindus will be below 50 per cent, Muslims will be at 35 per cent, and Christians 16.1 per cent by 2051. Another recent study has shown that Kerala’s Muslim population grew faster than the national average despite its better economic and educational levels. However, the Muslim fertility rate has also been dropping like those of other communities in Kerala, which had the country’s lowest decadal population growth during 2001-2011.

The fall in Christian population was seen for long as the fruit of its modern views, economic and educational advances (especially those by women) from the 19th century, and also large-scale migration to the United States of America and Europe. Kerala’s Syrian Christians provided India’s first women in many fields — the Indian Administrative Service (Anna Malhotra), the judiciary (the high court judge, Anna Chandy), surgery (Surgeon-General Mary Poonen Lukose), meteorology (Anna Mani), engineering (Chief Engineer P.K. Thresia) and politics (Annie Mascarene, Kerala’s first parliamentarian). They also gave India the largest number of nurses and nuns.

But today, the community’s demographic drop and rapid aging have spooked the Church, which is openly encouraging families to have more children by offering financial incentives. According to SMC, one lakh Christian grooms over 30 years are unable to find life-partners. Christians are also distressed by the recent decline faced by sectors in which they were dominant, like plantations, money-lending, liquor, while those where Muslims dominate, like hotels, tourism, bakeries, have thrived. Muslims from Kerala are among the richest Indians in the Gulf now. In fields like education, media, arts, where they had lagged behind for long, Muslims have recently advanced phenomenally.

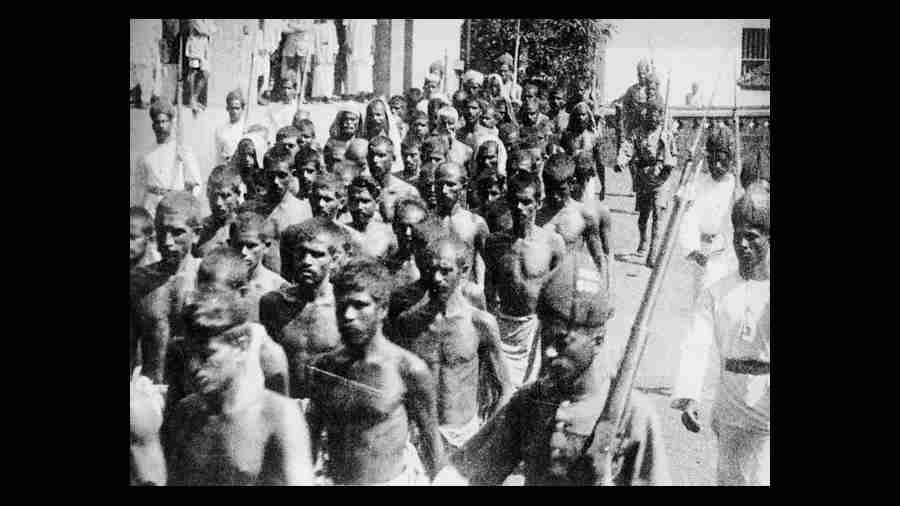

The shrill debate over the Moplah Rebellion of 1921, which left almost 2,400 dead and scarred Kerala forever, has raged right from its aftermath and continues even after 100 years. Besides British officials, prominent leaders like M.K. Gandhi, B.R. Ambedkar, Annie Besant, V.D. Savarkar and many Indian and foreign historians have written on the topic. Apart from Besant and Ambedkar, supporters of the British and of Hindutva — like Savarkar — have condemned it as a Muslim carnage against Hindus, Gandhiji criticized its violence and communal aspects but desisted from outright condemnation as it was part of the Khilafat movement. Left leaders and historians, starting from Soumyendranath Tagore — Rabindranath’s Trotskyist grand-nephew — had glorified it as a peasant revolt against the British and exploitative landlords. Left leaders like E.M.S. Namboodiripad, later on, took a holistic view, interpreting the rebellion as having contained both positive as well as negative elements, including Muslim extremism although its thrust was against imperialism and feudalism. Today, there is near-consensus among historians that the rebellion was a complex mass uprising with both positive and negative sides defying simplified interpretations. Yet, the debate never dies in Kerala.

M.G. Radhakrishnan, a senior journalist based in Thiruvananthapuram, has worked with various print and electronic media organizations