The sudden reorganization of Jammu and Kashmir has begun to adversely impact the process of Sino-Indian rapprochement that was picking up after last year’s informal summit between Narendra Modi and Xi Jinping at Wuhan. The two leaders were able to douse the tensions over the Chinese military intrusion in Doklam and they promised to come up with a road map for improvement in bilateral ties. Many expected China to be an achievement area for Modi’s foreign policy after Wuhan. That has now taken a hit.

The Wuhan spirit did bring some immediate gains for India. China finally agreed to a UN resolution to declare Masood Azhar, the Jaish-e-Mohammed chief, as a global terrorist. While this may have been more symbolic than substantial, it was seen as a message to Pakistan to act against Islamist terror, a source of worry for Beijing in view of Xinjiang’s proximity to the Af-Pak region. But the more substantial gain was in trade with China opening its markets to additional Indian products. As a result, in the 2018-19 fiscal year, India managed to cut its trade deficit with China by $10 billion. Its exports to China jumped 31 per cent year on year to reach the $17 billion mark. The trade deficit came down to $53 billion from $63 billion in the previous fiscal. The Indian pharmaceutical industry was particularly optimistic because China seemed convinced that cheaper Indian generic medicines could drive down its healthcare expenses.

But after the developments in Kashmir — they were opposed by China — Beijing seems to have turned edgy. It is said to have warned India that if Huawei’s proposal for developing India’s 5G network were not considered, Beijing may deny market access to important Indian products. The Chinese are masters of the ‘multiple pressure points’ approach: they could thus hit out with curbs on export of essential ingredients of pharmaceutical products. India’s pharma industry imports 80 per cent of its key ingredients from China. If this were to happen, the trade war between the United States of America and China would suck India in. That may please Donald Trump and lead to some US concessions for New Delhi, but the prospect of accessing the vast Chinese market would suffer.

Before the reorganization of Jammu and Kashmir, the Chinese were also sending positive signals on the long-festering border dispute. With the two sides close to a consensus on the ‘Central sector’ (Himachal-Sikkim), a return to Zhou Enlai’s proposals of the 1960s seemed on the cards. Zhou had offered Jawaharlal Nehru a swap: if India accepted China’s position on Aksai Chin, China would accept the McMahon line in the East and seal the deal. In hindsight, it seems to have been the most pragmatic offer for solving the border dispute and many have blamed Nehru for refusing it. But with Ladakh now a Union territory and leaders like Amit Shah clamouring to take back Pakistan-administered Kashmir as well as Aksai Chin, the Chinese position on the border will stiffen.

The Chinese know for a fact that India will not try to militarily take back Aksai Chin or the parts of Kashmir ceded to it by Pakistan but the unpredictability of the Modi administration worries them. The Chinese don’t like surprises unless they spring them. The real Chinese worry is over possible Indian efforts to promote unrest in Gilgit-Baltistan (among the local Shias), the North-West Frontier Province (through the Pashtun Tahafuz movement) and Balochistan (through the Baloch Raji Ajoi Sangar) in response to Pakistan’s support for militants in Kashmir.

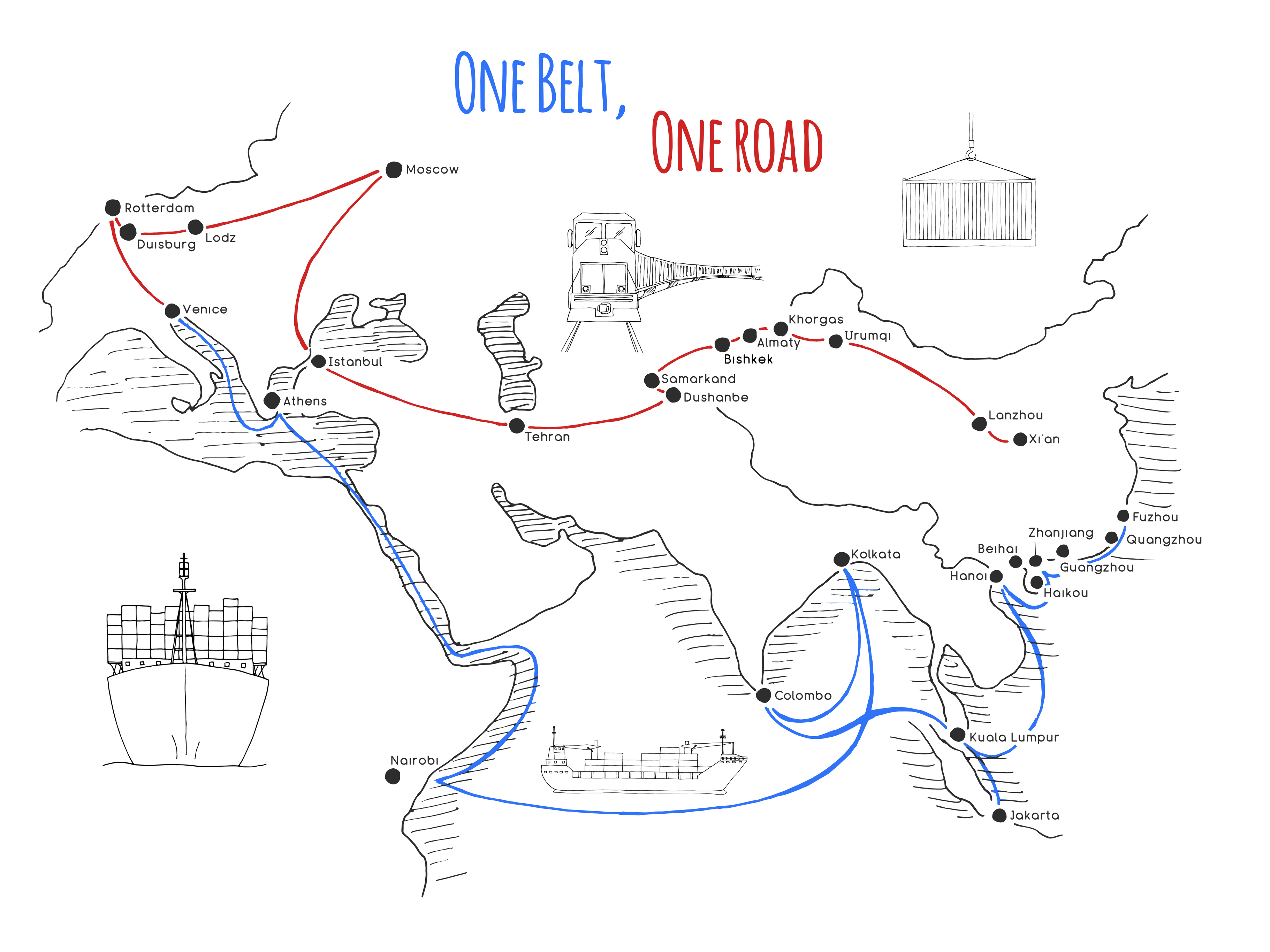

At Wuhan, Modi had pledged to take forward the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor that the Chinese are keen on. The corridor was expected to pass through the Northeast on the Calcutta-Kunming axis. With fresh strains in ties with China, India may pitch for an alternative route — Calcutta-Dhaka-Chittagong-Teknaf-Rakhine-Kunming — that would avoid the Northeast when Modi meets Xi. India can argue that roads on this alternative route are well-developed and they would make overland trade cheaper, but the real purpose would be to keep the Chinese out of the Northeast. With tensions rising, India cannot undermine its security concerns, but if the BCIM EC bypasses the Northeast, it would dilute efforts to situate it at the heart of India’s engagement with its eastern neighbours.