Excerpted with permission from Bruno Macaes’s Belt and Road published by Penguin India

The truth of the matter is that the Belt and Road poses a number of seemingly intractable challenges for India. Most obviously, it threatens to turn Pakistan’s occupation of part of Kashmir into a fait accompli. If the area becomes an important economic corridor for China, the conflict is no longer capable of being resolved within the limited sphere of relations between Pakistan and its much larger neighbor. Just before the May 2017 summit Beijing made one last effort to convince India to attend. In a speech in Delhi, its ambassador to India floated the idea of renaming the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. The suggestion was that the new name would no longer imply that the economic corridor ran only through the two countries, implicitly denying Indian claims to territory occupied by Pakistan. Left unsaid was what the new name might be and how it might avoid raising objections in Pakistan. Indian authorities never took the suggestion very seriously anyway, convinced as they are that the problems raised by the Belt and Road and its segment in Pakistan have more to do with increased Chinese presence than purely symbolic matters. When I asked Subramanian Swamy, a leading figure in the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, how his infatuation with the project of dividing Pakistan in four was compatible with his warm feelings towards China, he answered that India would be able to convince China that a war between India and Pakistan would not interfere with the Belt and Road. I was not persuaded.

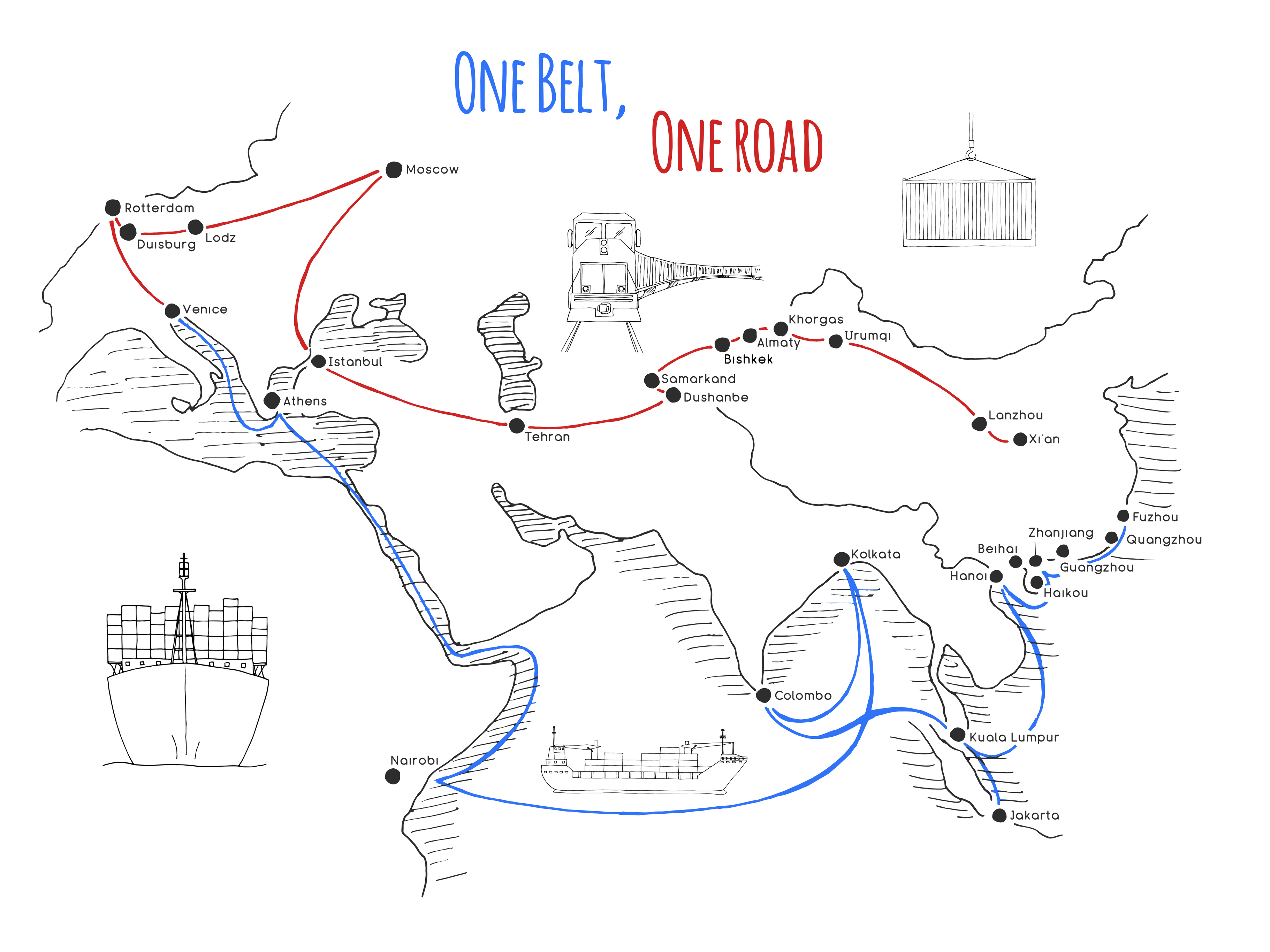

Economically, the challenge is, if anything, even graver. As a major economy hoping to remain on a trajectory of fast economic growth, India needs to develop deep international links and supply chains, most immediately in its neighborhood, but the Belt and Road may well force it into new forms of economic isolation, this time involuntary, as opposed to the years of Indian economic autarchy. New Delhi may even see in the Belt and Road a form of rewriting history by rebuilding trade and economic links between Europe and Asia while ignoring the Indian subcontinent, historically a meeting point for such trade and cultural networks.

The view from Beijing is just as cynical. While India remains for the time being a much weaker economy and state, it seems to have the forces of the future on its side. Chinese commentators have grown comfortable comparing China’s economic vigor with the slow decay of the ruling powers in Europe and North America. This mental framework has made conflict improbable, since China feels time is decisively on its side. With respect to India the power equation is examined in a different way. Perhaps China will be inclined to act against a rival if the relation of forces can only deteriorate in coming decades. Naturally cautious, Chinese state media outlets have not avoided talking openly about the possibility of a war with India. That China and India are growing strong simultaneously is an entirely new fact, one carrying significant risks.

The Doklam standoff ended with a choreographed disengagement on August 28. India agreed to withdraw its troops in a designated two hour period before noon and the Chinese did the same in a similar window that afternoon. The withdrawal was monitored from New Delhi in real time. By agreeing to discontinue construction works on the road, China seems to have met India more than half way, but it also used the occasion to state that it would exercise its sovereign rights in the future. More than a resolution of the crisis, the negotiation was meant to avert the risk of an accidental conflict. Troops from both countries remain in the area, but are now separated by a few hundred meters. Indian Army Chief Bipin Rawat quickly warned, “As far as the Northern adversary is concerned, flexing of muscles has started. Salami slicing, taking over territory in a very gradual manner, testing our limits or threshold is something we have to be wary about. Remain prepared for situations that are emerging gradually into conflict.”

India’s rejection of the Belt and Road may have triggered the confrontation that developed later in the summer. One month before the Doklam standoff, China had gathered about thirty national leaders at its first summit devoted to provide guidance for the Belt and Road. India announced just one day before the event that it would not be participating, explaining that in its current form the Belt and Road will create unsustainable burdens of debt, while one of its segments, the economic corridor linking China and Pakistan, goes through the disputed areas of Gilgit and Baltistan in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and therefore ignores Indian core concerns on sovereignty and territorial integrity. A statement released on May 13, 2017 by India’s Ministry of External Affairs explained: “We are of firm belief that connectivity initiatives must be based on universally recognized international norms, good governance, rule of law, openness, transparency and equality. Connectivity initiatives must follow principles of financial responsibility to avoid projects that would create unsustainable debt burden for communities; balanced ecological and environmental protection and preservation standards; transparent assessment of project costs; and skill and technology transfer to help long term running and maintenance of the assets created by local communities.” The journalist Ashok Malik from the Times of India called the boycott the third most significant decision in the history of Indian foreign policy, after the 1971 decision to back the independence of Bangladesh and the 1998 nuclear tests. “China would never force any country to participate in the Belt and Road initiative if it was too skeptical and nervous to do so,” an article in the Chinese state-run Global Times quickly responded. “It is regrettable but not a problem that India still maintains its strong opposition to the Belt and Road, even though China has repeatedly said its position on the Kashmir dispute would not change because of the CPEC.”

In June 2017 Chinese troops were spotted extending a road through a strip of land disputed between China and Bhutan. India perceived this as an unacceptable change to the status quo and crossed its own border—in this case a perfectly settled one—to block those works. The Doklam plateau slopes down to the Siliguri Corridor, a narrow strip of Indian territory dividing the Indian mainland from its North Eastern states. Were China able to block off the corridor it would isolate India’s North Eastern region from the rest of the country, a devastating scenario in the event of war.

Colonel Vinayak Bhat served in the Indian Army for over thirty years. He was a satellite imagery analyst, stationed in high altitude areas, where he also attended border personnel meetings as a Mandarin interpreter. I asked him why he thought Beijing was so determined to establish control over the Doklam plateau. After all, these border areas are far removed from any population center, and in many cases the actual border is difficult to determine —the demarcation goes back to old treaties between the Qing Empire and the British Raj and outdated, hand-drawn maps. Does it matter who gains an advantage here? “It matters,” Bhat told me emphatically. “If the Chinese control Doklam, especially South Doklam, they will be able to threaten the Siliguri Corridor. After the Doklam plateau it will all be downhill. You need anything from nine to sixteen battalions in these high altitude mountains for each defensive battalion. So that changes the calculations.”