The discussion around the new US president’s policy towards human rights concerns in India has been marked by two extreme poles. One is the woozily idealistic idea of an activist Biden administration actively meddling in Indian political affairs. The other is the coldly realist idea that the new administration in the United States of America, guided by material interests, would be as blithely unconcerned with the growing authoritarianism in India as the Trump administration.

In reality, the Biden administration possesses a range of options to gently nudge India towards democracy without risking a diplomatic fall out. A carefully calibrated policy in this regard is not just realistically possible, it would be in America’s own long-term interest.

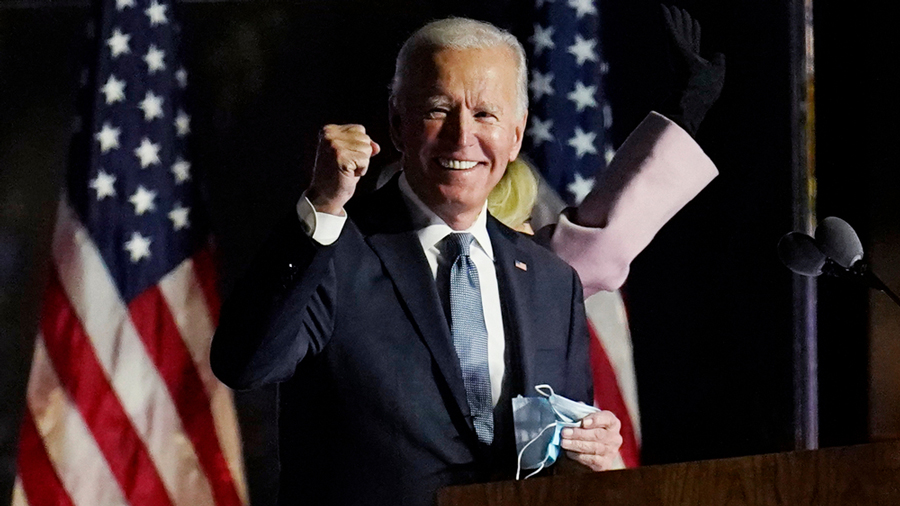

On the campaign trail, Joe Biden had promised to put strengthening global democracy back at the core of American foreign policy agenda. In an article for Foreign Affairs, Biden vowed to organize a Global Summit for Democracy during his first year in office. He stated that the summit would aim to “bring together the world’s democracies to strengthen our democratic institutions” and “honestly confront nations that are backsliding”.

No democracy is backsliding as rapidly, and with as grave consequences, as the world’s largest one. The latest Freedom House report revealed that India had registered the steepest yearly fall in its Freedom Index among 25 large democracies. If India’s democratic institutions keep declining at the present rate, by the end of Biden’s first term, India’s liberal democratic fate may well be sealed.

Ultimately, the burden of protecting India’s democratic institutions lies with Indian Opposition leaders and Indian citizens. They could, however, do with a helpful external environment. In the current form, Indian institutions pose little substantial check to Narendra Modi: a Parliament that has been reduced to a rubber stamp, a media that has been largely muzzled or co-opted, and a Supreme Court that was recently described by the eminent intellectual, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, as “slipping into judicial barbarism”.

A well-thought-out US strategy can help meaningfully constrain Modi’s room for authoritarian manoeuvre without provoking any fractious clashes in public. It would also make Biden’s democratic promotion talk more credible, and not just a convenient cudgel against rivals such as China and Russia. Soft power, after all, depends on credibility.

To understand how, one must try to comprehend Modi’s Jekyll and Hyde persona on the global and domestic stage, respectively, and how that fits into his political calculations. Unlike Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, Modi does not embrace the label of ‘illiberal democracy’. Neither does he clash with Western nations to accentuate his nationalist image, unlike Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte or Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Modi, in contrast, presents himself on the international stage as a responsible global statesman. He never tires of quoting Mahatma Gandhi and evangelizing India’s liberal and secular values. In other words, Modi seamlessly presents himself as the embodiment of India’s democracy on the global stage while constantly threatening it at home.

This well-respected global statesman image is crucial to Modi’s domestic appeal. Unlike many other global strongmen, Modi’s craves international and, in particular, Western acceptance and acclaim. This is the reason why he holds enormously hyped and personalized events with Western leaders such as Donald Trump and David Cameron. He invariably refers to global leaders as his friends — “my friend Donald” or “my friend Barack” — and ostentatiously hugs them in public to highlight their mutual affection and admiration. These moves are meant to pique the nationalistic pride of Indians and increase Modi’s domestic stature.

On the flip side, this makes Modi particularly vulnerable to official statements of disapproval from Western governments. For Modi’s well-crafted illusion to work, Western leaders must go with it. It is likely that Modi gamed the silence of an apathetic Trump administration before carrying out certain contentious moves, such as curtailing the autonomy of Kashmir or passing the Citizenship (Amendment) Act. Biden specifically criticized both these actions in a campaign document along with the implementation of the National Register of Citizens in Assam. In fact, the line expressing “disappointment” at the “restrictions on dissent” and “preventing peaceful protests” in Kashmir follows the line condemning “atrocities against Burma’s Rohingya Muslims”.

It is thus likely that Modi will closely observe Biden in the first year of his presidency and gauge whether Biden’s concern for human rights and democracy was just uplifting campaign rhetoric or part of a serious agenda. Modi’s judgment of Biden’s credibility on this front will probably be part of the calculations that decide whether he goes ahead with his next high profile moves that erode India’s democracy.

Therefore, it is not necessary for Biden to take an activist stance to act as a moderating influence on Modi. He just needs to show that, unlike Trump, he is serious about human rights protection. No one expects a high-pitched condemnation from a president who would vitally need the support of Modi on a variety of foreign-policy fronts — from containing China, to combating climate change, to strengthening global institutions. Moreover, the need to deepen ties with India on defence and trade would likely be prioritized over human rights, as has been the case with every previous president. Yet, given Modi’s sensitivity over his international image, all Biden needs to do is impress upon Modi that he would be willing to, whether subtly or bluntly, call him out.

Biden possesses many points of leverage. He can follow Obama’s lead in “privately” urging Modi that India should not be divided along religious lines. His addresses to Indian delegations must underline the importance of protecting minorities, and how that forms an important part of the “shared values between the two countries”. The state department, whose human rights reports have catalogued serious human rights abuses by the Indian government in recent years, must not shy away from expressing its concern or disappointment at key moments. Biden can even depute his progressive vice-president, Kamala Harris, to occasionally deliver some honest chastisement to the country from where she traces her roots.

The US Congress, which, to its credit, held hearings on the human rights situation in Kashmir last year, must also continue to closely monitor the situation of minorities in India. It can be pushed in this endeavour by the Progressive House Caucus — leaders such as Pramila Jayapal, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib — who hold advancement of human rights as central to their politics.

For decades, US presidents have claimed that the growth of American power is inextricably linked to the global advancement of democracy and liberal values. The reign of Trump, the only notable exception, is over. The sincerity of this conviction, often compromised in practice, will again be put to the test as the democracy representing a sixth of humanity drifts steadily into the grip of authoritarianism. In the coming decades, India will either be seen as a poster boy for ‘illiberal democracy’ or for the survival of liberal democracy in a challenging terrain. It is in America’s own self-interest that the latter vision prevails. Much will depend on whether Biden turns a blind eye as India slips off the democratic guardrails, or prods and coaxes India back towards them.

The author is a political columnist and research associate with the Centre for Policy Research, Delhi