After a four-year delay, when India’s decadal census gets underway, the exercise will be keenly watched by experts for reasons not prioritised by politicians — an enormously widening gender gap and a declining sex ratio at birth.

The two issues are intertwined, impacting each other, and, therefore, need to be understood together. The global gender gap index, introduced by the World Economic Forum in 2006, measures any significant improvement in man-woman parity in terms of economic opportunities, education, health and political leadership. According to a WEF report in 2024, India performs miserably, ranking 129 among 146 countries, with its GGI value at 0.641. This boils down to the stark narrative of a patriarchal view denying women their share of opportunities and disinheriting them of their rightful civilisational space.

But the downside of the social distortion has a direct bearing on India’s global ambition of becoming an economic superpower and an important geopolitical force. Depending on the steps it takes in the years ahead, the WEF predicts with cautious optimism that India is seductively close to becoming the world’s third-largest economy in the next five years and a developed nation by 2047.

The steps are a seeming pointer to correcting India’s immense gender gap. A closer look will make the picture clearer. India has achieved just about 36% gender equality in economic participation. Bridging the gender gap in employment would lead to an impressive GDP growth by another 30%. In other words, by ending discrimination against women, India could expand its GDP by a whopping $700 billion. The most deplorable side of the picture, however, is that most women work without getting paid.

The disturbing spin-off of the unrelenting gender gap has been brought out by a United Nations Population Fund report. India’s sex ratio at birth, it says, declined to an all-time low of 880 girls for every 1000 boys born in 2003-05. From that point onward, the SRB turned upward reaching 906-908 between 2007-2013. However, as NITI Aayog, a government policy think tank, disconcertingly admitted, the SRB declined further to 900 around 2015. Now, the chilling figure of nine million female births going missing between 2000 and 2019 as an outcome of sex-selective abortions, as unravelled by the Pew Research Center, exposes a horrid picture.

Despite a strong societal bias, female literacy has surged to a reassuring 92% now. This tremendous advancement in early schooling should have been a springboard of opportunities for women, paving the way for their economic empowerment and a larger share in politics. However, no significant rise in women’s status across the perimeter has been noticed. Currently, 13% of the Lok Sabha and 15% of the Rajya Sabha members are women. Though quite an improvement — women had a meagre 5% representation in the first Lok Sabha — the figures pale into insignificance before countries like Sweden, Norway, and South Africa where women’s share of the national legislatures is more than 45%. Of the total 11,569 officers who successfully entered the Indian Administrative Service between 1951 and 2020, just 13% were women.

Indian women of childbearing age also suffer from malnutrition. Exactly 53% of them (15-49 years) are anaemic, according to the Global Nutrition Report. But the trail of deprivation begins much earlier. Malnutrition is a major reason for below-five child mortality. Predictably the rate is significantly higher for girls. A baby girl, surveys confirm, is breastfed for a lesser duration than a male child.

The challenges get enormously tougher when she gets into the ways of the world.

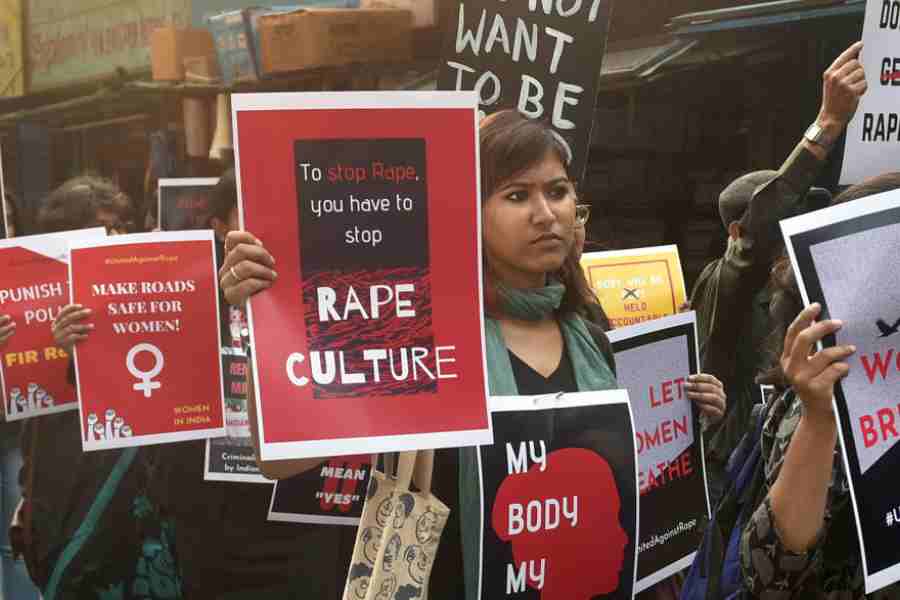

Between the brutal rape and subsequent death of Nirbhaya in Delhi in 2012 and a similar crime against a woman doctor in Calcutta in 2024, average rape cases registered by the police marked a surge. The trend peaked in 2018 when four cases were reported every hour. Now think of the thousands of sexual violence cases that go unreported.

The situation is bleak when it comes to the financial sector, an area that could have determined women’s economic resurgence resulting in their empowerment. In the buoyant corporate world, just about 5% of CEOs are women. The extent of economic loss and social discrimination caused by the gender gap could be accurately measured by a set of other facts. India’s female population, according to the 2011 census, was 58,75,84,719, out of which those in the age group of 15-69 were 38,70,70,504. However, just a little over 8.5 crore are actually engaged in the paid-work sector. The rest, understandably, run the household and work on the domestic front without remuneration. The issue that gets maximum criticality as far as the gender gap is concerned is sexual violence. "Violence against women and girls remains the most pervasive human rights violation in the world, affecting more than 1 in 3 women — a figure that has remained largely unchanged over the last decade,’’ the UN warned grimly in 2022. Even earlier, in 2019, it pointed to the disquieting reality of women being assaulted more often by their husbands or those close to them. “One in five women globally has experienced sexual and/or physical violence at the hands of an intimate partner in the past year,’’ revealed the document titled Women and Girls — Closing the Gender Gap.

The UN acknowledged the role of feminist activism in sensitising society against the horror of sexual violence and compelling national governments to enact laws to prevent domestic violence and sexual assault against women. Though mere legislation is no guarantee against rape, the heightened awareness and the fear of harsh law have worked as a deterrent.

Narrowing the gender gap also requires sensitising boys and men. The media and the entertainment industry can play a crucial role as social influencers in breaking gender stereotypes. Educational institutions, too, can raise the level of awareness about accepting women’s space in different areas.

Higher education, economic independence, equity in the professional space, and a larger share in politics for women can ultimately lead to gender parity. There is an urgency to give women more economic opportunities, unshackle their entrepreneurial talent, and free them from the stranglehold of the patriarchal straitjacket. This is how India can close its frightening gender gap and gain an excellent rank on the global index.

Manimala Roy is a Delhi-based economist. She works on gender and migration