The chairman of Larsen & Toubro, S. N. Subrahmanyan, wants a 90-hour workweek. In a statement that has led to outrage on the internet and memes, he also added, “How long can you stare at your wife?” He is justly being taken apart by netizens but he isn’t the outlier in a society that knows better. Constructing a woman’s identity and purpose in opposition to good, honest work is offensive enough but I wonder whether women who work are also not supposed to stare at their partners beyond a stipulated time. But Subrahmanyan’s statement identifies the man as the default ‘worker’ in the relationship, while the woman as the ‘wife’ is relegated to domestic spaces where she distracts her husband from the serious business of ‘work’. While this reveals a great deal of embedded misogyny and patriarchal smugness in one of the more influential people in the country, what is perhaps more interesting is what makes such a statement possible. And why Subrahmanyan is a symptom of a far older disease.

Subrahmanyan is not the first person to ask for (or be trolled for) extra work-hour weeks. India’s economy has been neoliberal since 1991. This meant freeing the market from most governmental restrictions and exponentially increasing the potential for profit-making. After all, the neoliberal claim is rather simple — the State has created a level playing field and, so, anyone willing to put in the hard work is bound to succeed; those who don’t are either lazy or simply don’t have the ‘right stuff’ in them. This may be a simplification, but enshrining the need to work as the central tenet of the economy chimes nicely with Subrahmanyan’s words which imply that the more you work, the better it is for you and your country. That and a seemingly unconnected bit of misogyny.

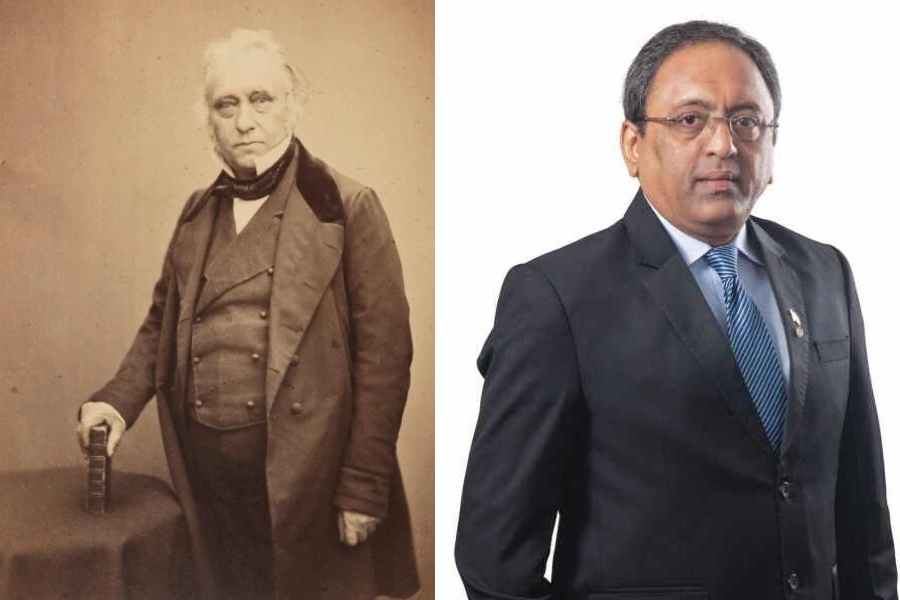

As it turns out, they are connected in ways that have nothing to do with neoliberalism. The history of Western education in India can be traced back to the infamous Macaulay’s Minute in 1835. Far from an altruistic move by our colonial overlords, its sole purpose was to create a race of loyal and beholden clerks to help with the smooth running of the empire. As Macaulay pointed out, this wouldn’t be accomplished by simply teaching the natives English but by turning them “English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect.” Even though we have come a long way, our continuing dependence on Western education has ensured that the colonial legacy lives on in the most insidious of ways. Something of how 19th-century British culture constructed the ideas of Englishness is part of some of the most cherished ideals of our so-called middle class.

In his seminal, early-twentieth-century work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Max Weber outlines the connection between the rise of capitalism and Protestant theology in Britain and the Germanic states. His argument can be reduced to this: in a fallen, irredeemable world, where you can’t do anything to determine your own salvation, your capacity of work is a sign that you are among god’s “Elect”. From this it naturally follows that prosperity arising from work is also a sign of divine favour. This apotheosis of labour made the earning of money almost an act of worship and when the time came, it gave capitalism (whose purpose is to maximise profit) an aura of celestial legitimacy. On the one hand were extraordinary feats of daring that led to an empire of riches beyond the dreams of avarice. But this was possible because of culturally sanctioned qualities of industry, thrift, and common sense, the very foundational tenets of the identity of the British middle class. This was more than convenient because it allowed a reconciliation between a religion whose founder stated that it is easier for a camel to pass through a needle’s eye than for a rich man to get to heaven and naked imperial greed. However, dominant ideologies of cultures do not exist independently of each other. The rise of capitalism also marked the hardening of gender roles at the time.

In the 18th century, burgeoning imperialism created for the first time a clear demarcation between public and private spaces in Europe. The world was growing smaller, but it was also now full of strange, alien spaces from the Western point of view. The public space was where unimaginable money could be made, but it was also rife with dangers, both physical and spiritual, and, therefore, required masculine intervention. The private space back home was thus constructed in opposition as an unpolluted shrine to cherished ideals central to how the British saw themselves. By the 19th century, women became firmly identified with this private domestic space and eventually became custodians of goodness, purity, and charity. The ideal woman was not supposed to sully her high-mindedness with dross work. Rather, she should be the embodiment of Western civilisation’s best ideals — a haven for the weary man tired after dealing with the cut-throat ruthlessness of the world of money. It wouldn’t be too much to say that the highest ideals of Western civilisation were maintained by this fine balance between man’s aggressive activity and woman’s transcendent passivity. Deprived of opportunities in public life, a woman’s primary role was to be beautiful, like a breathing ornament of great spiritual worth, to be stared at!

It was inevitable that most of this would make its way into our normative ideas via an educational system still tied to a distinctly colonial legacy. Subrahmanyan’s statements are made possible by certain assumptions that have become part of our country’s cultural fabric. These assumptions determine not only how we approach the importance and the role of ‘work’ in our lives but are also interlinked with ideas of gender roles and social and moral worth. What is perhaps more dangerous is that Subrahmanyan is entirely oblivious to the implications of his statement since they appear to him to be simply about ‘how the world works’.

It’s been 34 years since liberalisation, and 78 years since Independence, but it seems that Macaulay’s plan is still producing, in very unexpected ways, “a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect.”