On August 27 this year, Yale-NUS College, a collaboration between Yale University and the National University of Singapore, announced that it will close and be merged into a new interdisciplinary honours college within the NUS called New College. From 2025, Yale will only have an “advisory” role.

The announcement brought a jolt of historical irony. Back in 2015, I’d heard Peter Salovey, the then president of Yale, speak on liberal arts education in Asia. At the time, I was in the process of moving from California to Delhi, to be part of the early cohort of faculty at Ashoka University, and to set up a department of creative writing at the new university. After Salovey’s talk, hosted in Delhi by Ashoka, I asked him why Singapore, a state not particularly known for free thought, was collaborating on the American model of liberal education. His response had struck me as prescient: that the government of Singapore knew that a messy kind of democracy was coming to the country soon and that a liberal arts education was the best way to prepare its citizens for it.

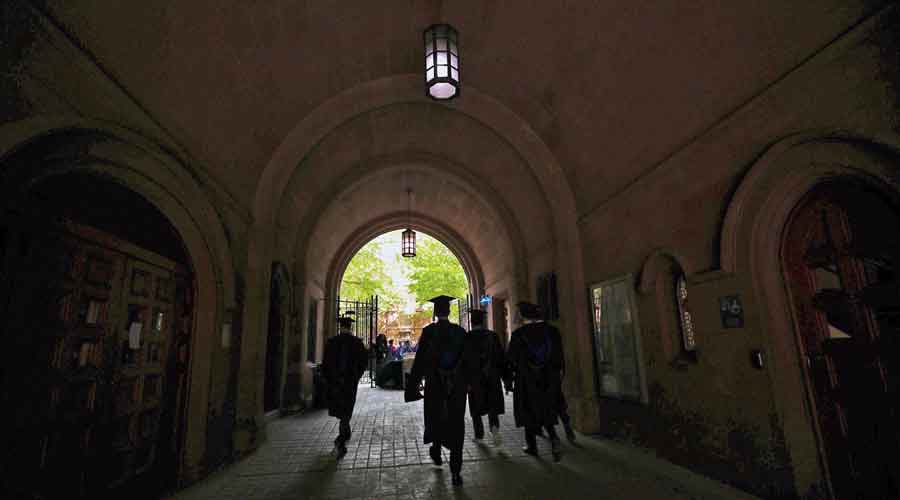

There was a new excitement for innovative liberal arts education across the Pacific, and I felt a part of it myself. More specifically, I recognized a culture of interdisciplinary creativity such as I’d seen in my previous institution, Stanford, translated into a new Asian demand for innovative multidisciplinary education. At the heart of this sharply-felt demand were the professional needs of rapidly evolving knowledge economies. It was the kind of interdisciplinarity that went beyond narrowly technocratic or financial aptitude that was the core mandate of specialized schools of business or technology. This liberal arts model, with obvious corporate enthusiasm behind it, was inevitably elite and expensive. It was generously supported by philanthropic entrepreneurs from the new digital economy. It was fairly clear why an economically ambitious and technologically progressive state such as Singapore was interested in it — and why it also appealed to the forms of private philanthropic higher education emerging around some of the major cities of India.

But soon enough, and rather inconveniently for these early champions, it turned out that the word, ‘liberal’, has many more shades of meaning than can be easily contained within the shiny enthusiasm for multidisciplinary flexibility. Instead of being contained within an apolitically conceived disciplinary framework, liberal education yearns for greater freedom — from hierarchies and bureaucracies of the past, from the burden of colonial traditions, and, most importantly, the freedom to speak truth to power. But the relation between these different imaginations of education — notably between disciplinary innovation and political freedom — was always uneasy in Asia.

The most striking success story came from South Korea, where, as Martha Nussbaum has argued, American liberal arts education has helped modernize and democratize an older tradition of Confucian humanism, opening it up to women and the working classes. The revitalization of the older humanistic model has happened primarily as an act of decolonization following the Japanese domination of Korea, where American missionaries ended up playing a key role in the nation’s recovery of its identity through education. This, however, has been a rare instance of creative synergy; nothing like this has quite happened in the other major Asian countries. The global prominence of traditional Chinese culture and thought in the Confucian tradition has also been the goal behind the Chinese government’s investment in liberal arts education, but the cultivation of active citizens or independent critical thinkers in the Western sense has never been part of this goal.

Hong Kong has been caught in a historical tension — between a shift away from a British colonial model of single-subject degrees and a more broad-based liberal education that has been criticized as dissident by pro-China leaders. While supporters of this education in Hong Kong have lauded its departure from the rote-learning curricula of the mainland, others have blamed it as an instigator of student unrest — especially since the protests of 2014. It’s a familiar sight for us in India where debates about the meaning of free speech and the right to dissent on university campuses have been exploding just at the time when disciplines were opening up to another kind of freedom in elite, private, higher-education spaces.

*******

American liberal arts education developed as humble, local and provincial. While closely linked to the church, it was free from the larger structures of government. Without the cosmopolitan ambitions of the medieval European university, “the American college in the nineteenth century was a hometown entity,” writes the education historian, David Labaree. In a land of competing churches, founding a college was an effective way to “plant the flag and promote the faith”. A college was a solid claim for a sleepy country town to get on the map so that it could demand a railway stop, a county seat, or even the state capital, and in turn, to raise the value of local real estate — which possibly explains the remote and provincial locations of so many liberal arts colleges in the US.

The liberal arts model requires significant freedom and decentralization — institutions and faculty must have the liberty to choose their own curricula and adapt them to local needs. But with freedom comes responsibility, which is often felt as unwelcome. And many Asian governments remain keen to centralize higher education and are unwilling to grant significant liberties to institutions.

It seems that the honeymoon period for liberal arts in Asia is now over. With a rising youth population, significant student talent sharpened by the traditional Asian attention to education, the expanding middle class and its increasingly ambitious vision for higher studies, this new educational model should continue to do well. But it’s also clear that the new liberal arts institutions will dwell as islands in a prickly mix of admiration, suspicion, and hostility in their local communities and experience incendiary relationships with their governments. If the mistrust between these islands and the oceans surrounding them strains beyond a certain point, the compact, whether tacit or explicit, will break, as with the unforeseen disintegration of Yale-NUS.

(Saikat Majumdar is Professor of English and Creative Writing at Ashoka University)