Consider the following two socio-economic trends in India over the past few decades. First, income inequality has worsened significantly since the early 1990s. According to the estimates of the International Monetary Fund, India’s income Gini index (a common measure of inequality ranging between 0 and 1 where 0 indicates complete equality and 1 indicates complete inequality) rose to 0.51 in 2013 from 0.45 in 1990. An Oxfam report finds that 73 per cent of the wealth generated in 2017 went to the richest 1 per cent, while 67 crore Indians who comprise the poorest half of the population saw 1 per cent increase in their wealth. The economists, Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty, note in a recent study that current inequality in India is at its highest level in 96 years.

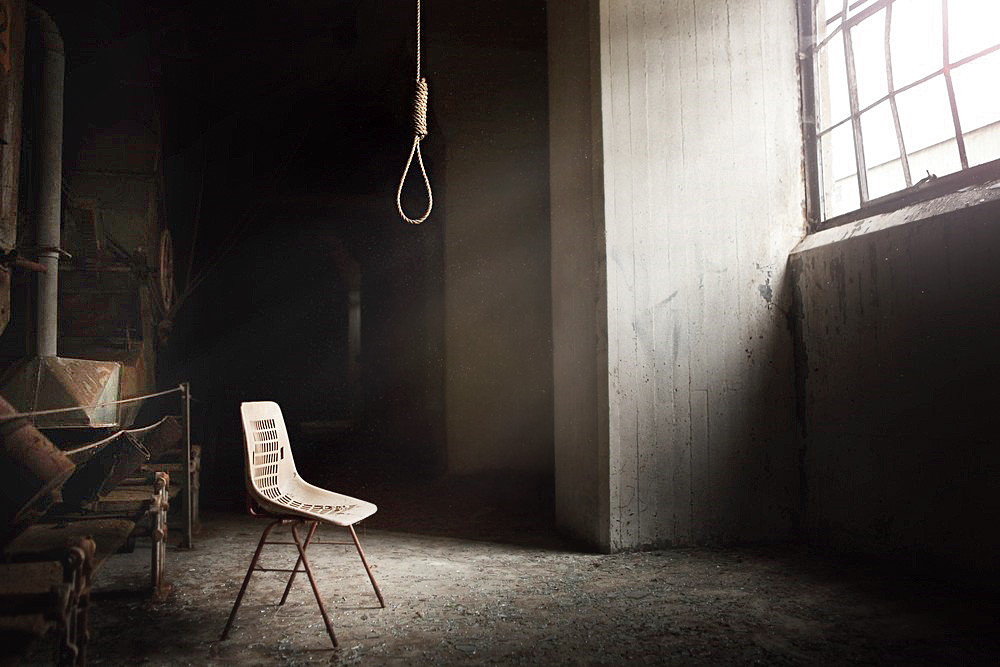

The second trend has to do with population mental health and well-being. According to a recent report of the Lancet commission, mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders and schizophrenia are on the rise in India. Present estimates show people with mental illnesses account for nearly 6.5 per cent of India’s population, and is projected to increase to 20 per cent by the end of this decade. Without factoring in suicide, mental health issues are projected to reduce economic growth in India by more than nine trillion dollars in the next 12 years. A World Health Organization report shows that India is the most depressed country in the world, followed by China and the United States of America.

What if the above two trends are interlinked? That growing inequality is one of the primary factors responsible for the rise in mental diseases in India? No matter how surprising it appears to be, a substantial body of research in social epidemiology and public health over the past few years has found evidence that rates of mental illness are higher in societies with large income differences.

The effect of income inequality on mental health, first documented by the epidemiologists Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson, and the psychologist, Oliver James, in a 2006 article published in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, seems to run primarily through psychosocial mechanisms. It is posited that growing income disparities and polarized societies increase social anxieties, such as worries about how we are ‘seen’, narcissistic personality disorders such as delusions of grandeur, all of which erode our social life. The worst affected might withdraw completely and engage in health compromising behaviours like substance abuse.

Relaxing and spending time with family and friends are essential for mental well-being — and yet, as per the psychosocial explanation, this is where inequality hits. As Pickett and Wilkinson note in their new book, The Inner Level: “The reality is that inequality causes real suffering, regardless of how we choose to label such distress. Greater inequality heightens social threat and status anxiety, evoking feelings of shame which feed into our instincts for withdrawal, submission and subordination: when the social pyramid gets higher and steeper and status insecurity increases, there are widespread psychological costs.”

According to a recent study in Social Science & Medicine, the psychosocial explanation of the effect of income inequality on mental health is consistent with the biology of chronic stress, new studies of the neuroscience of social sensitivity, and concepts from evolutionary biology. Income inequality is linked to lower levels of social capital and generalized trust, suggesting that inequality acts as a social stressor. Chronic stress impairs memory and mobilizes hormones (glucocorticoids, for example) that increase the risk of depression. Since in highly unequal societies, people have to deal with unstable relationships, workplace stress and lack of social connectedness, they tend to fall prey to maladies of the mind.

Psychosocial mechanisms are not the only pathways through which inequality harms mental health. An alternative explanation is based on what is called the neo-material mechanism. It has been suggested that more generous welfare regimes, public spending, more comprehensive social security and investment in human capital development are all characteristics of more equal societies. The relation between income inequality and mental health may therefore be mediated by these neo-material factors. But tests of neo-material versus psychosocial pathways from income inequality to mental health conclude that psychosocial factors, such as social capital and trust, mediate the relationship, whereas neo-material factors, such as public expenditure on health or social services, have relatively little explanatory role.

How can the issue of rising mental health distress owing to growing income inequality be tackled? A recent article in The Economist notes that reversing the cycle of widening inequality and mental distress requires a broad civic awakening. There are many examples of civic awakenings in history that have yielded economic, social and political reforms. Such movements could build a more equal world which might be free of maladies of the mind.