September 10 was World Suicide Prevention Day. On that day this year, according to media reports, a 15-year-old girl in Aligarh set herself alight with kerosene after telling her father that she had been raped by two men when she went outside to the toilet on September 7. Reportedly, the police said later that they had found her walking on the railway tracks on September 7, saying she wanted to end her life. They had dropped her home.

Another report says that in the first week of the month, a 24-year-old woman used poison to kill herself after she was raped by four men on her way back from her class at a beautician’s. Although she told her family what had happened, they chose to keep quiet at the time. Two more news items say that on September 19, a 15-year-old in Delhi, studying in Class X, hanged herself after being stalked and harassed and, two days later, a 14-year-old, studying in Class VII in Zirakpur, Bihar, tried to kill herself with poison because she was being stalked. She survived.

This is just one month, random pickings.

On September 12, The Lancet Public Health published a paper called “Gender differentials and state variations in suicide deaths in India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2016”. Besides underscoring the lack of research on female suicide in the country, experts said that the scale of suicides by Indian men, women and young people comprised a national public health emergency. The findings show — briefly, without tracing changes from 1990 — that, in 2016, India had 17.8 per cent of the global population but recorded 36.6 per cent of suicides of women across the world — 94,380 — and 24.3 per cent of suicides among men globally. Suicide is the first cause of death among Indians of the 15-29 and 15-39 age groups; counted together, 1,45,567 young people below 40 killed themselves in 2016.

When Indians talk of public health programmes, do they include suicide among malaria, tuberculosis and polio? Suicide to the Indian is an embarrassingly private act that must be hidden away, just as the agony of a raped girl, or the terror of a sexually abused child, or the helplessness of a psychologically embattled member of the family is a household disgrace that must be suppressed as far as possible. Family silence seems to have led to the suicide of the 24-year-old in September.

This social attitude was enshrined in a law that made attempted suicide a criminal act until 2017. Concealment was, therefore, doubly important, so vulnerable survivors were denied professional help, while cause of death in suicide was often misreported. Suicide figures may actually be higher, feel some commentators on the Lancet paper. Without an articulate national programme of awareness that relates suicide to individual and social health, little is likely to change. All the situations of silenced pain mentioned in the previous paragraph can lead to suicide. Research has shown that survivors of rape and childhood abuse develop suicidal tendencies in the face of challenges in later life, and are also prone to depression. Depression again, as well as certain other mental illnesses, can lead to suicide.

Silence and imagined shame exacerbate a tragic problem, although these are not the only causes. Many causes are in the public domain. The paper shows that married women, mostly young, form an overwhelmingly large proportion of female suicides. From minor marriage, torture for dowry, domestic violence to sheer powerlessness, the issues that cause this group despair are well-known and bristling with protective laws. Yet public discourse somehow evades mentioning the scale of married women’s suicides. Why do laws fail? How, in spite of them, does society collaborate in perpetuating violence against women? How many suicides are covered-up murders? Each issue generates its own questions: for instance, how should girls in underprivileged families be protected so that their parents are not forced to marry them off for sexual ‘safety’?

India is good at making women invisible in life, work and death. It took a study by the Thomson Reuters Foundation with contributions from international experts to show that India is the most dangerous country for women in the G-20, up from fourth place in 2011. The suicide data match this perfectly. But, like in most countries except China, in India more men are recorded as committing suicide than women. Marriage, conventionally believed to be a protective factor, does not stop Indians from ending their lives. In 2001, when, according to the National Crime Records Bureau, 16,415 farmers committed suicide, nearly 70 per cent of all suicides were by married people, says another report. Of these, 70.6 per cent were men and 67 per cent women. Opponents of the anti-dowry law would argue that married men commit suicide because of lying women; this belittles the tragedy of human beings deciding to end their lives.

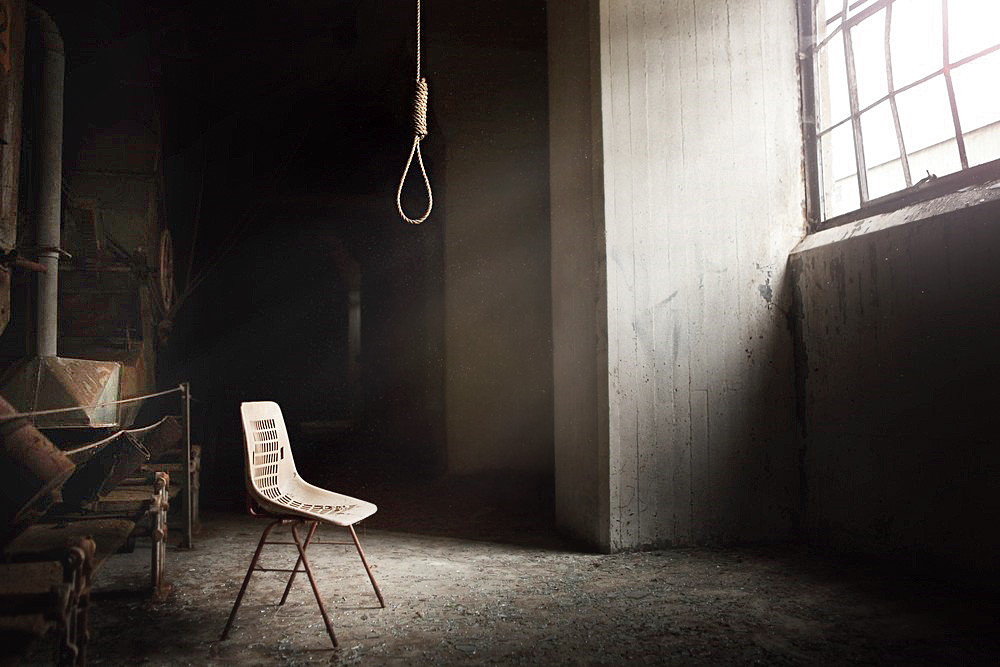

Triggers are different for men and women, and it is the task of a nuanced public health policy to work these out, together with regional differences, so that timely intervention and psychosocial therapy become possible, and treatment for mental illness and substance abuse accessible. China has succeeded in reducing the suicide rate among rural young women with a public health programme that included the banning of pesticides. Analysing the commonest methods in India — hanging, poison, burning with kerosene — can lead to constructive conclusions too.

What must first be fought, though, are shame, repression, the devaluing of women, and silence. In India, three times more women attempt suicide than men. The failed female suicide is dismissed as attention-seeking and her fragility ignored. In the July 2015 number of The Indian Journal of Psychiatry, Lakshmi Vijaykumar argues that although men’s mortality outstrips that of women, women’s attempts at suicide, or morbidity, added to their mortality, make the burden of women’s suicidal behaviour greater. This fact must be confronted, not glossed over.

The September suicides I mentioned are all of young unmarried girls. Their stories demonstrate, nakedly, how shame kills. Shaming is based on women-repressive ideas of bodily purity and family honour. One girl reportedly killed herself after being raped by two men, the crime made possible by the lack of security in an underprivileged environment. Self-harm was her first, instinctive response. The report reveals the need to sensitize the police, for they rescued her from the railway tracks but apparently did not warn her family or arrange for support. Two others wanted to die because they were being stalked. Yet the amended law after the Delhi gang rape of December 2012 criminalizes stalking. The older girl died possibly because her family chose silence over her need for justice.

The humiliation of forced sex affects both boys and girls. The same values that condemn raped girls force silence and ‘manliness’ on little boys in similar crises. They are ‘invisible’ too, although a 2007 investigation by the women and child ministry uncovered a shockingly huge number of them. In July 2017, a 13-year-old boy killed himself with rat poison after being raped by a man in a neighbourhood close to Mumbai. It is not just society that enforces silence, the law may help too. A terrible silence laced with the fear of criminal action overlay the world outside heteronormative society until this month. How many young people have killed themselves, unable to adjust to society’s expectations of ‘normal’ sexual preferences or prevented from living with the one they love?

Formulating a public health programme for suicide prevention in this country has to begin with determined honesty as well as the ditching of received wisdom. Just as marriage is not a protective factor in India, so education is not always a rescue route for young people. Three of the four girls mentioned earlier were stalked or raped on their way to or from classes — this is common — while aspirants to the country’s best professional institutions being trained in a city like Kota, or students in the best schools or in the most highly developed states are seen to be particularly vulnerable to depression, guilt and fatal self-harm. Is the Indian government ready to take stock?