The passing of Bishan Singh Bedi at a time when Indian fast bowlers are serially flattening the opposition in this World Cup underlined the transformation of Indian cricket in my lifetime. Indian cricket teams were once built around a total lack of fast bowling. Between the English tour of 1964, when I began following international cricket, and Kapil Dev’s debut in Pakistan in 1978, B.S. Chandrasekhar, a quickish wrist spinner, had a reasonable claim to being the fastest bowler in the side. India’s demon quick through the Sixties was Ramakant Desai, a 5’ 4” seamer from Bombay.

The Nawab of Pataudi’s masterstroke as a captain was to reconcile himself to this reality. Instead of wasting his time trying to build a balanced bowling attack, he gave himself up entirely to spin. My earliest memories of Test cricket are of Bapu Nadkarni bowling interminable spells only to be replaced by another left-arm spinner, Salim Durani.

In 1962, on a tour of the West Indies, Pataudi’s bowling attack in Port of Spain consisted of the two left-arm spinners mentioned above, a part-time off-spinner, Polly Umrigar, and a leg-spinner who was mainly a batsman, Chandu Borde. India’s opening bowlers were Rusi Surti, a very medium paced all-rounder, the lineal ancestor of India’s bits-and-pieces players, from Eknath Solkar to Shardul Thakur, and M.L. Jaisimha, an opening batsman with no real claim to being a bowler at all. Jaisimha was an early example of a specialist Indian opening batsman pressed into service to take the shine off the new ball. He had distinguished successors, Budhi Kunderan and Sunil Gavaskar amongst them. The main function of India’s seamers in this era was to bat (and field) while the spinners did the bowling.

But it wasn’t till E.A.S. Prasanna was joined by B.S. Chandrasekhar, S. Venkataraghavan and, finally, B.S.Bedi that this redundancy of spinners became a feature of Indian cricket, not a bug. This quartet (with Venkat on drums) were our Beatles. This subtle re-making of a redundancy of spinners into a slow-bowling vanguard was led by Bedi, often literally. It was normal for Bedi to bowl the third or fourth over of the innings after the cricketing gods had been appeased with token overs of seam. His ability to bowl with godlike control with a brand-new ball was the cornerstone of India’s wins abroad between 1971 and 1974. Bedi wasn’t always the bowler who won us the match; that distinction sometimes went to one of the other spinners like Chandrasekhar, who ran through England’s second innings at the Oval in 1971, but he was the rock on which we built our church.

It was the only non-violent bowling attack the world had ever seen. This was not out of choice — we didn’t have the weapons to be violent with —but at its best it created a strange magic not seen before or since. The madness of leading with spinners

in all conditions, on every type of pitch, from Perth to Port of Spain, was a natural experiment that tested the limits of slow bowling. It couldn’t last; it needed the unlikely coincidence of three exceptional spinners at the top of their form at roughly the same time. The end came in that ice-breaking tour of Pakistan when Father Time, flat pitches and Zaheer Abbas conspired to end the career of this coven of spinners as a force in cricket.

But before that happened, Bedi & Co built a new silsila, one in which all the ustads were spinners, where the default jawaab to every cricketing savaal was spin. One part of this tradition still exists and comes to life when India plays a Test series at home. The fast men become optional, the early overs of seam become an opening set for the main act, where Ravichandran Ashwin, Ravindra Jadeja, Axar Patel and Kuldeep Yadav do the real, slow-bowling thing.

But not abroad. When India tours outside South Asia, normal service is resumed and the team defaults to the global template of three or four seamers and a solitary spinner. Given the seamers we have, this is both understandable and effective, but for fans of my generation, schooled in the idea that spinners are bowlers for all seasons, it leads to atrocities like Shardul Thakur playing ahead of Ashwin, the greatest spinner we have produced since Bedi called it a day. In our time-warped minds, this is like dropping Jasprit Bumrah for a part-time spinner.

Going by their figures, Ashwin and Jadeja are the greatest spinners India has ever produced. Whether one uses strike rate or average runs per wicket or total wickets taken, they are way ahead of, say, Prasanna or Bedi. My cricket fantasy is to see an Indian touring side with Ashwin, Jadeja, Yadav and Patel picked as the principal bowlers with Hardik Pandya and Shardul Thakur standing in for Abid Ali and Solkar: shine removers who bat a bit. It’ll be magical to see what these contemporary slow men make of the challenge of doing everything, from making the initial breakthrough to wrapping up the tail.

It'll never happen, of course, because it would be a crime to rest fast bowlers as exceptional as Bumrah, Mohammed Shami and Mohammed Siraj on helpful wickets. But I can see Ashwin rising to the challenge of bowling in the first hour at Old Trafford and Jadeja relishing the opportunity of doing more than giving his captain control on the first day in some foreign field.

What we can’t replicate is the vulnerability of that time. Indian cricket in the 60s and 70s was a shamateur sport. There was no money to be made from the game; players were paid to play by institutional patrons. Those that didn’t have honorary, white-collar employment led precarious lives. Bedi used to frequently tell a story about India’s Test players being daily wagers. They were paid by the day and once, Bedi said, when India beat the opposition in four days, they weren’t paid for the fifth.

Their vulnerability wasn’t just economic, it was physical too. This was a time before helmets and while this absence endangered all batsmen, it endangered Indian batsmen more than others for a couple of reasons. First, we didn’t produce fast bowlers in domestic cricket and, therefore, had little experience of playing them. Second, unlike the great Pakistani cricketers of that time, several of whom played seam bowling routinely in England, very few Indian cricketers played county cricket.

As a result, many first-rate Indian batsmen had difficulties with the short ball. Brijesh Patel comes to mind as does Mohinder Amarnath, before the helmet transformed him into one of the best players of fast bowling in the world. Indian batsmen and Indian fans were weaned on the cautionary tale of Nari Contractor having his skull broken by the wicked Charlie Griffith, who figured as a kind of Ravana in India’s cricketing folklore. The threat of mortal injury loomed over Indian lower-order batsmen simply because their cricketing environment left them unequipped to deal with short-pitched bowling. When Bedi declared the innings closed at five wickets down in Sabina Park, it was less a statement than just basic concern for the well-being of his team.

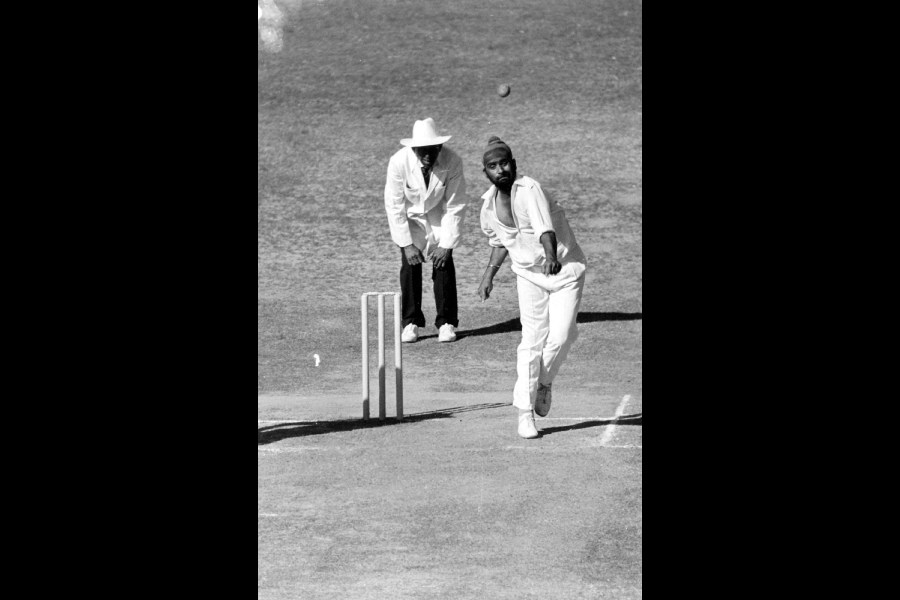

It was in this precarious world that Bedi and his teammates won their unlikely victories. No one should be nostalgic for that straitened time but the wins that those teams, the poor relations of world cricket, pulled off against the odds were peculiarly precious for the fans who followed them. Nothing will quite compare with their memory of a pear-shaped, patka-wearing genius, pivoting weightlessly on a barely earthbound toe, looping the ball skywards, with peaceful yet perilous intent.

mukulkesavan@hotmail.com