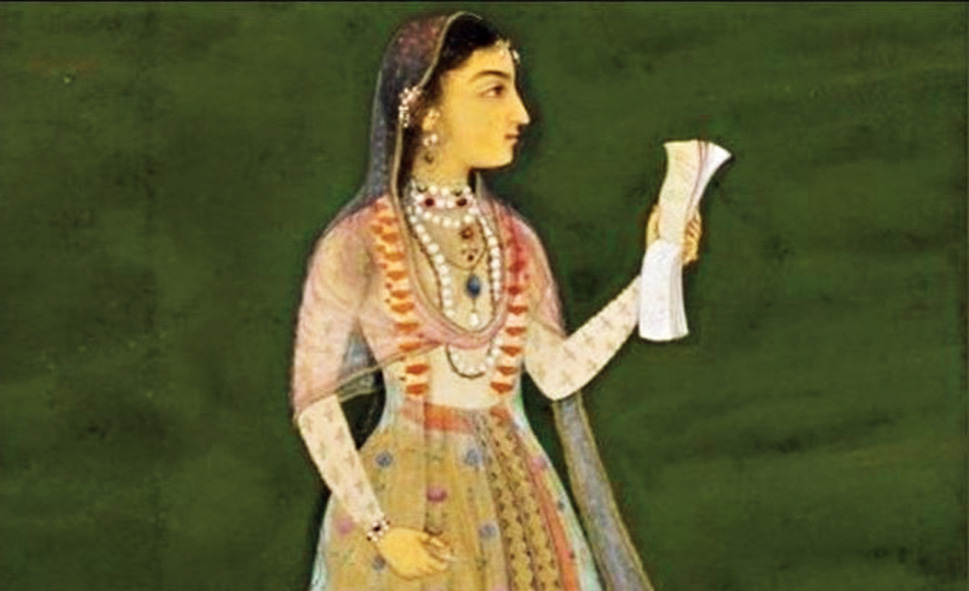

Why is it that no feature film has been made on the dramatic life of Begum Zeenat Mahal, the last ‘Queen of India’? She ruled over what remained of the Mughal Empire during the twilit reign of the last ‘Emperor’, Bahadur Shah Zafar, negotiating life in the reduced circumstances of the Red Fort with a mix of dignity and desolation, pride and panic. A woman of grit but no luck, she did her Queenly and courtly best to secure the throne for her only son, Mirza Jawan Bakht, in preference to Zafar’s two older sons by his previous marriages. But Fate was against her, as was Fate’s living representative — the British raj. In whatever she tried to do, she floundered. She kept her son out of reach of the mutinous rebels in 1857 with a view to secure his future throne. She did her best to protect her husband from the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune but alas. She had to go with her exiled and de-crowned husband to exile in Rangoon, as Yangon was then called. Her departure from the Red Fort has to be the most poignant moment for that site since the capture and humiliation there of Dara Shukoh. Zeenat Mahal lies buried beside her husband who pre-deceased her by four years, in a suburban niche, not far from Yangon’s Shwedagon Pagoda.

There is no film made on another Zeenat-like figure nearer our times — Zuleikha Begum, the wife of Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin, known to history as Maulana Azad. Married at age 13, the deeply thoughtful wife of the scholar-rebel, the secular Divine, whose world was in books and in struggle, Zuleikha lived in Calcutta even as her husband scoured India fighting for freedom and, after the Muslim League declared Pakistan to be its goal, for an un-divided Hindustan. In 1942, as the Congress under Gandhi was entering its most decisive phase in the struggle, Azad was in their Calcutta home. Called for the Quit India Resolution meeting in Bombay, he left home abruptly. Did she protest? Did she say ‘Think of the family...’? All we know is Zuleikha followed him to the outer door and stood there, framed in her silent singularity, and as her husband got into a car, bade him a silent khuda hafiz. Azad probably knew that he would be arrested immediately after the Resolution was passed. Along with Nehru, Patel, Kripalani and other senior leaders of the Congress, he was lodged in the Ahmednagar Fort prison for nearly three years, writing in the genre of epistles with no thought of when, if ever, they would be published. And watched, entranced, the love-life of a pair of sparrows in his cell, describing it in an essay he titled “Chirey-Chiri ki Kahani”. And during that long period of plangent isolation, a human twosome was to be sundered. Her husband a prisoner, Zuleikha died in Calcutta. She lies buried in Calcutta, he in Delhi.

There is no feature film on Sarojini Naidu, born to letters, to music in letters, educated in Britain, drawn in an indefinable way to the wholly different and difficult personality of Mohammed Ali Jinnah, married to yet another contrast in ‘type’, Govindarajulu Naidu, a general physician from Hyderabad, with whom she had five children, while also becoming known and hailed as the ‘Nightingale of India’, presiding over the Indian National Congress, travelling to the United States of America at Gandhi’s behest to counter the negative impact of Katherine Mayo’s Mother India, braving police action in the Dandi satyagraha, serving in the Constituent Assembly and becoming the first governor of the United Provinces, only to die very shortly thereafter from a brief illness, asking her nurse to sing to her.

No film on Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, on Aruna Asaf Ali, on Mridula Sarabhai, heroines of our freedom’s great struggle in the twentieth century, the first a socialist, the second a communist and the third an individualist who rescued abducted and abandoned women during the Partition riots in a way no government agency could have and went on to make Sheikh Abdullah’s cause in Kashmir known to the wider world. No feature film has been made on Chandra Narayanaswami Muthulakshmi, later known as Muthulakshmi Reddy, who, born to the Devadasi community in the princely state of Pudukkottai, had to struggle to gain access to education but then went on to become the first female student admitted to a men’s college, the first woman House Surgeon in the government hospital she joined, the first woman legislator in British India moving for the abolition of the Devadasi system.

No film has been made on M.S. Subbulakshmi either, whose childhood in Madurai as the gifted daughter of a Devadasi mother and her later life of iridescent brilliance in music on the silver screen demand an outstanding film.

Why have these films not been made?

For one reason, above all. We have a great sense of mythology in India but on historical terrain we stumble. We are unable to face psychological crises, nuanced character, dilemmas. We are unable to take the tension of true portrayal. Heroics work with us, reality is troublesome.

But there is another reason as well. We have had and have, even in our times, some great actresses. But those who can do a range of character portrayals are hard to find, hard to direct. Our Judi Dench is yet to be found and cast for the roles of India’s historical heroines.

That amazing English stage and screen actress turns 85 tomorrow, December 9, 2019.

Having played Virgin Mary, no less, Ophelia in Hamlet, Juliet in Romeo and Juliet, Lady Macbeth (picture) in Macbeth on stage, Queen Elizabeth I in Shakespeare in Love, the duchess in The Duchess of Malfi, Queen Victoria in the teleplay, Mr Brown, Iris Murdoch in Iris, she is celebrated today as ‘M’ in the reboot of the James Bond series. In those very contemporary, very techno-savvy spy films, Dench’s portrayal is, in a word, astounding. Her voice, rusty, dusty, croaky, has become almost her signature. But it is her searing eyes that do it. In one memorable shot, when a would-be assassin faces her, gun in hand, Dench looks at him, through him, and into his very soul with her onyx eyes and, just as he is about to pull the trigger, is pulled down to safety behind a desk. It goes to her and to her director’s credit that in those micro-seconds the terrorist has the viewer in the barrel of his dare and she in the beam of her glare.

Judi Dench, had she been one of our great actresses, would have portrayed Zeenat Mahal, Zuleikha, Sarojini Naidu, Kamaladevi and all the others I have named as to the manner born. But we need not despair. Perhaps one more generation needs to pass, one more era of vain frivolity to spend itself before we re-discover, in the dust of forgetting and inattention, the lost jewels of our squandered bequest.

As we toast Judi Dench on her birthday tomorrow, we must toast too that future equivalent of hers in India and ask her to glare, glare into our philistinism and neutralize its heedless heroics.