Ira Mukhoty’s second book promises to be timely, topical and trendy, but fails to deliver on several counts. Catering to the current penchant for popular history, the book is a hybrid of the scholarly and the literary. In this book, unlike in her debut Heroines: Powerful Indian Women of Myth and History, Mukhoty aspires to create a revisionist history of the Mughal empire through the use of less-popular texts by and about women. These are augmented by the crumbs of data on women’s lives, possessions and enterprises that are picked up by a quick authorial scan of canonical texts (mostly biographies, autobiographies and contemporary histories) and architectural monuments. The book seeks to cover the 200-odd years of empire building of “the most magnificent dynasty the world has ever known”, and reconstruct the lives of the women who were part of its everyday life. This includes the women of the harem, or as Mukhoty calls it, the zenana. She asserts that the idea of the ‘Oriental harem’ was a European construct, a fantasy of white male visitors suffering from a mix of libidinous envy and cultural mistranslation: “They could not understand the reason for a Mughal woman’s influence and power, attributing it to an emperor’s weakness, or worse, to incest.”

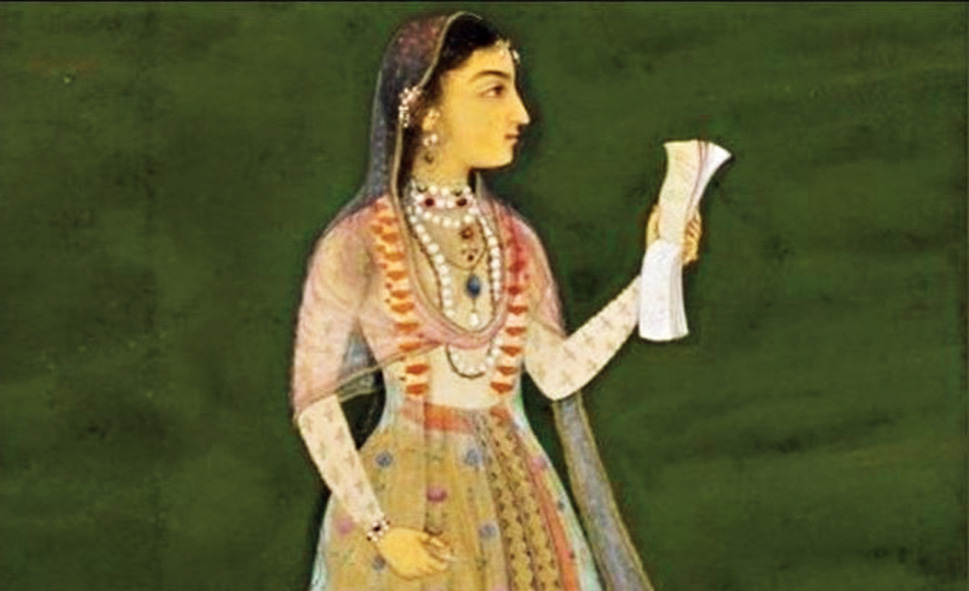

By recounting the story of the princess who was sacrificed to rival chieftains but was welcomed back to court after a decade (Khanzada, Babur’s sister, among the most powerful and best recorded of the women in the book), the political games played by the milk mother of a 13-year-old Akbar (Jiji Anaga), the tale of the girl who wielded the imperial seal (Jahanara Begum, picture), the girl who wrote the history of her foremothers and aunts (Gulbadan Begum, author of the Humayun-nama) and several others, Mukhoty seeks to debunk stereotypes about the nature of the space and the inhabitants of the Mughal haraman. We are assured that Mughal women had a great deal of personal liberty, were sophisticated patrons of literature, art and architecture, owned property, ran businesses, drank alcohol and smoked hookahs. Another concern for the author seems to be to establish that Hindustan was never an exclusively Hindu Brahminical space and Hindu and Muslim blood and philosophy mixed freely (for example, Jahangir’s mother was the Rajput princess, Harkha Bai). This anxiety to establish India’s multicultural past becomes overpowering at times.

Mukhoty cannot be unaware that sex and progeny are some of the oldest currencies available to women to be used in power negotiations. Yet she continually seems to be surprised by the influence the women of the family of the Mughal Padshah exercised on their menfolk. Although her politics is impeccable, in establishing it she elides a crucial problem in the treatment of sources. If Europeans are to be criticized for mistranslating Mughal culture, how can the same texts be used to dismantle the stereotypes they helped generate? The book tells us that Mughal women had some freedom while the dynasty was still nomadic, but as the empire solidified (from Akbar onwards), their role grew less flexible, although no less powerful. This is not very novel since this phenomenon has been noted in the lives of early European women too.

Mukhoty writes with imaginative vigour and evocativeness, although the unrelenting present tense does not help. The chosen material is too slight to justify the book’s length and without substantial archival work the commentary begins to sound repetitive. For all its tall claims, Daughters of the Sun fails to scintillate.

Daughters of the sun: empresses, queens & begums of the Mughal empire By Ira Mukhoty, Aleph, Rs 699