In the third week of January 2020 — exactly a year ago — I was in New Delhi, working in the collections of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. I first discovered the archival riches of the NMML in the early 1980s, and explored them most fully while living in Delhi between 1988 and 1994. In those years I would spend a couple of days a week in the NMML, exploring its repository of private papers of major (and minor) figures in modern Indian history and digging deep into its holdings of old newspapers.

In 1994, I moved to Bangalore. I no longer had daily access to the NMML, and made do with a few trips a year. These were generally in January, April, September and November, thus escaping the brutal heat of summer and the sapping stickiness of the monsoon too. I would book myself for a week or ten days in a boarding house in New Delhi, within walking distance of the NMML. I would reach the Manuscripts Room at 9 am, as soon as it opened, colonize a desk by the window, order my files, and settle in for a concentrated day’s work. Apart from a short break for lunch and two shorter breaks for chai, I would take notes until 5 pm, coming back the next day for more.

I have worked in dozens of archives around the world, but the NMML has always been my favourite place to do research in. The reasons were various — the setting, a tree-laden campus rich in bird life, behind the magnificent Teen Murti House; the range of primary materials on all aspects of our history; the capable and helpful staff; the planned and unplanned meetings with other scholars who came to work there.

For the past quarter-of-a-century, I have made at least four, sometimes five and even six, pilgrimages each year to this shrine for historical researchers. When I was there last January, I had no clue 2020 would be any different. Then the pandemic set in, and for the rest of the year I was marooned in South India. Even if I had somehow got on a flight to New Delhi, I would have found the NMML shut.

Nonetheless, through the course of the year this much-loved archive kept me company anyway. I was finishing a book on foreigners who joined the freedom struggle, based in large part on research previously conducted in the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. And I was reading manuscripts of younger scholars, these likewise drawing on the collections of the NMML. In the summer and autumn of 2020, I read draft chapters of a biography of the socialist leader, George Fernandes, written by Rahul Ramagundam, and of a biography of the Bharatiya Janata Party icon, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, written by Abhishek Choudhary. I also had several long conversations with Akshaya Mukul, who is working on a new biography of Jayaprakash Narayan.

These three book projects have four things in common. First, when published all will be major and perhaps definitive biographies of the individuals concerned. Second, since these books are about important (and controversial) historical figures, they should command a wide readership. Third, the subjects of these books were all opponents (sometimes implacably so) of the Congress and its pre-eminent leader, Jawaharlal Nehru. Fourth, none of these books could have been conceived, researched or written without access to the rare and rich materials pertaining to Fernandes, Vajpayee and JP kept in an archive named after their common political adversary.

This was not an accident. Though named for Nehru, the NMML was never intended to be partisan in its orientation. That is why biographers of JP, Fernandes and Vajpayee have to conduct much of their research there. So must biographers of other celebrated anti-Congress (and anti-Nehru) politicians such as Shyama Prasad Mookerjee and C. Rajagopalachari.

Unlike many other Indian institutions, the NMML was lucky in the people who built it. Its first two directors, B.R. Nanda and Ravinder Kumar, were outstanding as scholars and as administrators. Working with Nanda and Kumar were a team of excellent archivists who sourced manuscripts and newspaper collections from around India, indexed, catalogued and preserved them, and made them accessible to scholars.

Over the decades, thousands of books and dissertations have been written on the basis of the NMML collections. Anyone working with any seriousness on any aspect of modern Indian history had to spend time here. Whether one was desi or videshi, young, old or middle-aged, whether one was a social historian, an economic historian, a cultural historian, a historian of science, a film historian or sports historian, a student of feminism or environmentalism or socialism, one began and often ended one’s research at the NMML.

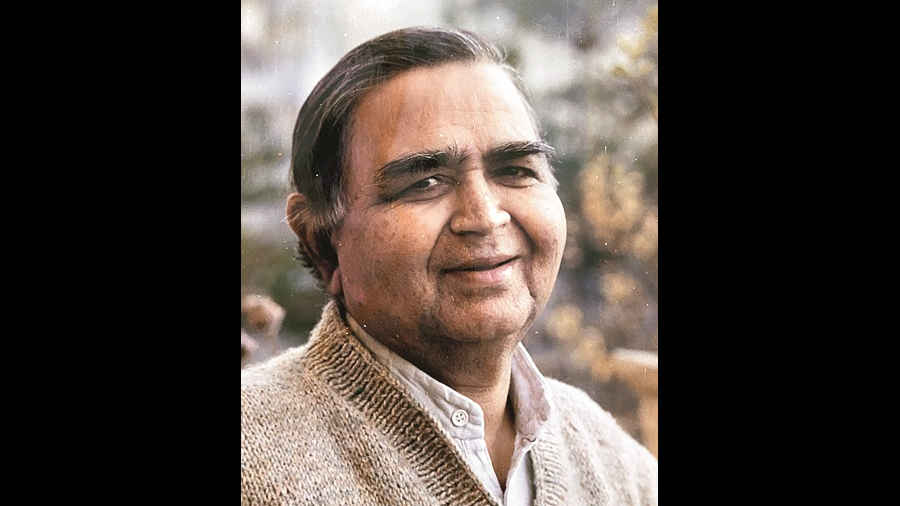

With no disrespect to the other men and women who made the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, perhaps the person who best embodied its spirit and character was a scholar named Dr Hari Dev Sharma (picture). A historian from the Punjab, he joined the place in 1966, shortly after it was established, and worked there for more than three decades. Many of the most important collections at the NMML were acquired through the skill, industry and selflessness of Hari Dev Sharma. These include the Fernandes, JP and Rajagopalachari papers mentioned above, as well as an extensive collection of the papers of Mahatma Gandhi himself. It was also Sharma who oversaw the oral history collections, these often based on interviews with freedom fighters that he had himself conducted.

From February to December 2020, while deprived of physical access to the NMML, I kept in touch with this great institution via the manuscripts I was reading. While discussing Fernandes with Rahul Ramagundam, or Vajpayee with Abhishek Choudhary, or JP with Akshaya Mukul, the figure of Hari Dev Sharma often came into my mind. These scholars are all too young to have met the man, although they know that it was archivists like him who made their scholarship possible. I was myself fortunate both to have known Dr Sharma and be a direct beneficiary of his work and his wisdom.

Short and stocky, Haridevji was clad always in a kurta-pyjama, coloured white and made of khadi. He came to office riding his own scooter, stoutly refusing a sarkari car. As I write this, I can picture us meeting on a wintry January morning, on the steps of the Library building. I have just disembarked from an autorickshaw, and he has just parked his Vespa and taken off his helmet. As we come across one another this sort of conversation ensues:

The Archivist (in Hindi): “Kaho Ram, kaise ho? Bung-lore se kab aaye?”

The Researcher (in Hinglish): “Meri flight kal raat ko pahunchi, Haridevji.”

The Archivist: “Toh is baar kya dekh rahe ho?”

The Researcher: “Main Gandhiji ke disciples par kaam start karna chahta hoon.”

The Archivist: “Tab ao mere saath kamre mein.”

Had I not run into Haridevji on the Library steps, I would have proceeded to the Manuscripts Room, shooting in the dark, beginning my research unguided and unaided. Now, having met him and being taken to his office, my time amidst the NMML’s collections would be more profitably spent. I wished to know what Gandhi’s closest followers did after the Mahatma’s assassination, he asked? In that case I must access the collection of the economist, J.C. Kumarappa, focusing in particular on his correspondence with Vinoba Bhave and Mira Behn. Then I should look at the materials on the Frontier Gandhi, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, contained in the papers of D.G. Tendulkar and Kamalnayan Bajaj. And so the stream of recommendatory advice would flow, making the researcher’s task so much easier.

Hari Dev Sharma retired as deputy director of the NMML in 1999, and passed away the following year. Ever since, whenever I have entered the NMML I have imagined meeting him, helmet in hand, and his taking me to his room for instruction. However, the last eleven months of 2020 passed without my stepping into my favourite archive at all. I don’t know whether I will see it in 2021 either. Perhaps that is just as well, for in recent years the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library has entered into a steady and probably irreversible decline. The fine archivists who retired were not replaced, while important collections donated by well-meaning Indians remain uncatalogued, gathering dust. Meanwhile, the NMML’s administration has been commanded by its political bosses to disregard scholars and scholarship and, instead, devote its attention to the construction of a hideous new building on the lawns. This is ostensibly a museum to honour all of India’s prime ministers but is — like so many other ugly structures under construction in New Delhi — in essence a monument merely to the vanity of the present prime minister.

One doesn’t know in what form or shape the NMML will survive the mayhem of the Modi years. A centre of intellectual excellence, once staffed with archivists like Hari Dev Sharma, once so hospitable and welcoming to scholars of all generations, ideologies and nationalities, has become a sad and forlorn place, bereft of creativity and the capacity for self-renewal. As someone who knew the NMML in its prime, I feel fortunate, in having masses of notes from it that will sustain me for the rest of my life, as well as guilty, since scholars younger or as yet unborn will never be able to draw as deeply from this once great archive as I myself have.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in