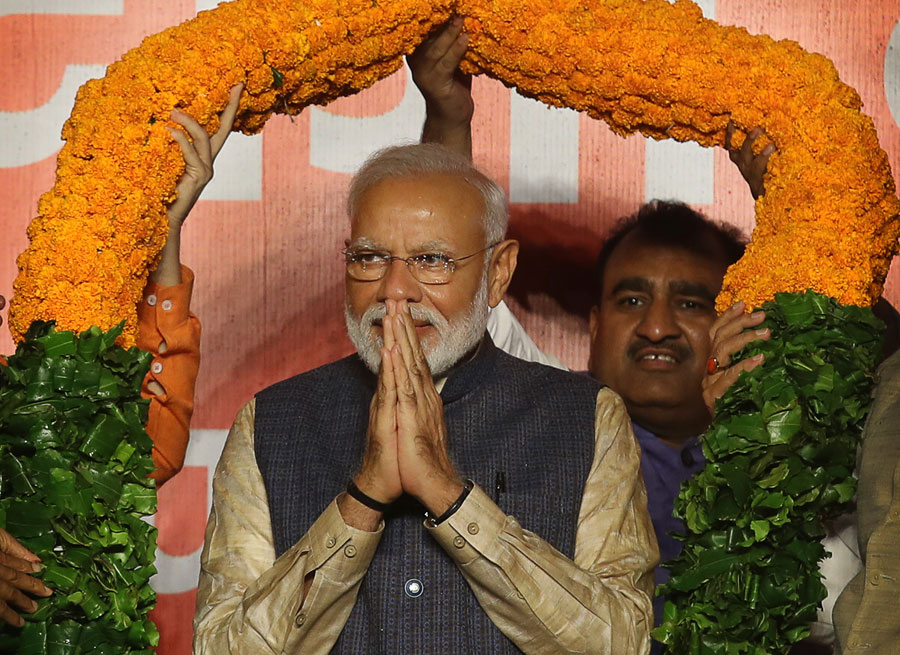

Cometh the hour — a general election — cometh the man — Narendra Modi. There can be no doubt about the fact that the spectacular mandate delivered in favour of the Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance — it has come to power with an improved tally — is, in reality, proof of India’s unshakeable faith in the leadership of Mr Modi. Of course, this stunning endorsement of the prime minister cannot be explained by a single factor in a political economy as heterogenous as India’s. In West Bengal, for example, the BJP’s ascendancy — it must have taken the party by surprise — can be attributed to such causes as disaffection with the Trinamul Congress as well as the switch of the vote from left to right. Odisha, along with Kerala and Tamil Nadu, has not been swept away by the saffron surge. But in nearly every other state, most notably in western India, the Hindi heartland and Uttar Pradesh — the state that still holds the key to power in Delhi — Mr Modi continues to stride the political landscape like a colossus. Even the coming together of influential regional parties in UP was not strong enough to resist Mr Modi’s advance. It must be conceded that the agrarian crisis, economic stagnation, unemployment or the fraying pluralism — the issues that were central to the Opposition’s campaign — have been rejected comprehensively by the voters. The reasons are not far to seek. Mr Modi’s assurance of a strong government, the anxieties regarding the fragility of a non-BJP dispensation, the BJP’s barely-concealed attempts to polarize the electorate and its milking of the bogey of terror, combined with the might of its electoral machinery, found many more takers than expected. The India of old and its politics, unknown to the BJP’s opponents, seem to have changed in fundamental ways. The BJP has succeeded in transforming the national election into a kind of presidential contest. Consequently, in New India, the prime minister towers above all parties, including his own.

Power is invested with stupendous responsibilities. The prime minister thus has his task cut out in specific areas. Fixing the economy must be one of the prerogatives of the new government. New strategic developments — the deterioration in the Middle East — and such old concerns as Pakistan must be addressed. Another test lies in Mr Modi’s ability to allay concerns about his commitment to pluralism and inclusive welfare. The choice to make or unmake the nation lies with him.