The Indian Space Research Organisation’s successful landing of Chandrayaan-3 on the moon is a tremendous achievement for our space programme. As we celebrate this inspiring success, we must reflect on the historical path that has led to this scientific achievement. We must seriously consider the lessons learnt and chart a carefully thought-out path for the future.

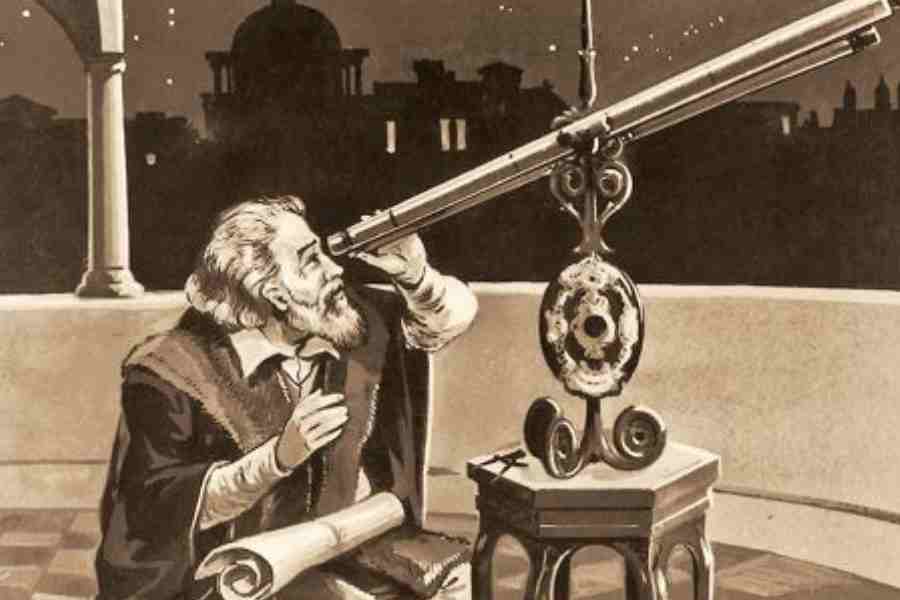

How did we get here? Who took the first important steps to lead us to such ambitious space programmes? For a long time in history, it was believed that the Earth was at the centre of the universe till the Polish astronomer, Nicolaus Copernicus, rejected the geocentric (Earth-centred) theory propounded by Aristotle and Ptolemy and proposed the radical idea that it was actually the sun that is at the centre of the universe. But it was Galileo Galilei, the Italian astronomer, physicist, and engineer, who experimentally validated Copernicus’s theory of heliocentrism and laid the first foundations for modern science and modern astronomy. Giordano Bruno, an Italian astronomer and mathematician, also reaffirmed the heliocentrism of Copernicus, rejecting the traditional geocentric theory accepted by the Roman Catholic Church. Bruno, however, met with a tragic death for maintaining his unorthodox views and challenging the authorities. Modern science, especially the advances in modern astronomy, would have been inconceivable in a geocentric universe. Had Galileo not validated Copernicus’s theory through the telescope, modern-day space programmes would not have existed.

Although Copernicus’s heliocentrism is radical, his personal life remained unaffected. He did not seem to receive any vicious backlash in sharp contrast to Bruno who suffered a torturous death for challenging contemporary beliefs. Galileo’s life seems to fall between Copernicus’s and Bruno’s. While he had his ups and downs, his life was the perfect plot for a play. In fact, Bertolt Brecht does exactly that in his famous play, Life of Galileo, which creatively dramatises this perfect plot. While taking marginal liberties, the German playwright par excellence highlights Galileo’s poverty, his ordeals, and his continuing passion for science despite several personal trials and professional hurdles.

While corroborating Copernicus’s theory, Galileo laid the foundations of modern science. He ruthlessly eliminated anything that he did not believe to be a valid source of knowledge, including belief, faith, and unverifiable scriptures. He stressed the need to inculcate relentless critical thinking when practising science. Galileo undermined the authority of the Church as he did not consider religious authority to be based on valid knowledge. When he refused to relinquish his views, citing that they had been scientifically validated through experiment, the Church — not out of ignorance but with full knowledge, as Galileo’s former pupil headed it at the time — placed him under house arrest. Scene 14 in Brecht’s play depicts the house arrest of Galileo. Brecht wonderfully dramatises this story and lays bare the complexity involving truth, deception, pragmatism, individual ethics, and Galileo’s dogged pursuit of science.

Galileo secretly completed his magnum opus, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems — Ptolemaic and Copernican — during his house arrest. He thus makes a pretence of surrendering to the authorities. With this seemingly morally weak move, he allows himself to transfer his theories into writing, making them independent of him and his life under threat. He finds this pragmatic move to be better than suffering like Bruno for the sake of science.

The differing perspectives of science and religion are well-known and their antagonistic relationship is clear despite some claims to the contrary by Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo. However, what is interesting about Brecht is that in addition to these two perspectives — science and religion — a third perspective forms the underlying architecture of the play that continues to have relevance today. This is the perspective of the traders. Galileo, who is utterly wedded to objectivity, pleads for the autonomy of science. This, interestingly, includes making it independent of money and business. For instance, he bluntly refuses when a group of traders offers to help him fight against the Church in exchange for sharing his knowledge to help them profit in business. Galileo’s clear stand remains at the core of significant scientific discoveries. However, the extensive use of science in modern life is a cause for concern. The application of science and technology is associated with making profits and not enough attention is paid to more significant concerns, such as the exploitation of humans and natural resources.

One reason for recalling the history and the foundation of modern science in the context of Chandrayaan-3 is to remind ourselves of the radical contribution of Copernicus, the sacrifice of Bruno, and the validation by Galileo to ensure that science would be autonomous, free from the constraints of either religion or trade.

The other reason is to look critically at the subtle but significant connection between India’s scientific feat in landing Chandrayaan-3 on the moon and exploring minerals on the lunar surface. While the landing was an impressive achievement for our scientists and a testament to their dedication and teamwork, we should think carefully before using such scientific advances for commercial gains as that can have alarming consequences.

We are already struggling with severe climate change and unprecedented natural disasters caused by reckless exploitation. But we may not have learnt any lesson from this experience. We need to reconsider our approach to mining the moon lest we wreak havoc on the lunar environment, repeating the mistakes of our British colonisers who carelessly exploited India for its natural resources.

A. Raghuramaraju teaches Philosophy at the Indian Institute of Technology, Tirupati