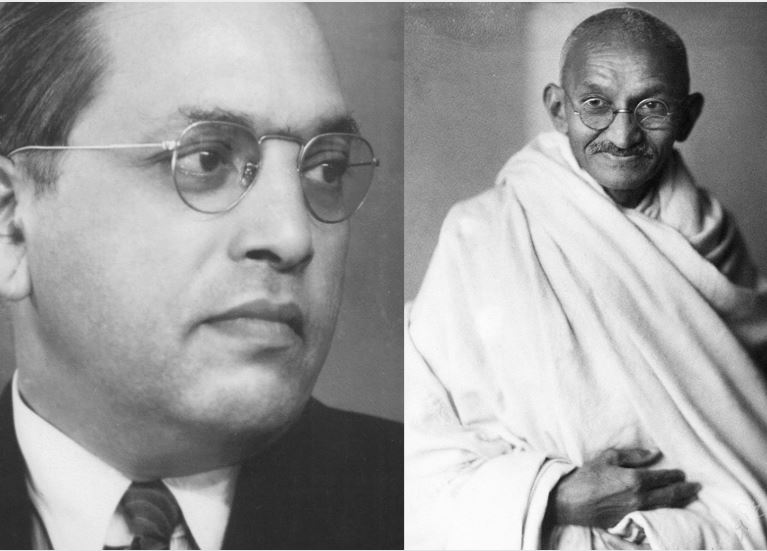

At the time of Independence, more than a quarter of India’s population had been subjected to deprivation, discrimination and degradation on account of the prevalent caste system. In establishing the Republic — a State with the rule of law — it was important to ensure that every citizen is treated equally before the law and was given equality of opportunity. But ensuring equality under those circumstances would have only led to ‘formal’, as opposed to ‘substantive’, equality. In drafting the Constitution, B.R. Ambedkar thus suggested that the State must ensure “the principle of equality of opportunity and at the same time satisfy the demand of communities which have not had so far representation in the State.”

Thereafter, the Constituent Assembly recognized that the State must take positive action to remedy the historical injustices faced by the disadvantaged groups. An advisory committee was tasked to decide the nature of these positive actions. The Poona Pact had already legitimized reservations as one such remedy; the advisory committee returned with a similar suggestion, recommending the inclusion of provisions in the Constitution for reservation of seats in central and provincial legislatures and quotas in public employment for certain castes and tribes based on their backwardness.

Using reservations to ensure an equitable distribution of resources, State power and representation is what we understand as ‘distributive-equality’. This is different from ‘status-equality’ that seeks to ensure that people treat one another as equals. Status-equality involves dismantling the notion of hierarchies in society. It seeks to assure that people treat each other as equals, and that society is not marked by status divisions.

Indian law provides mechanisms — the abolition of untouchability or the Prevention of Atrocities Act are examples — to achieve status-equality. But these mechanisms are not strong enough for two reasons: First, they do not cover every social identity group that requires protection against discrimination and fail to acknowledge the intersectionality of identities; second, these legislations are not comprehensive enough to capture every kind of differential treatment. Moreover, the discourse on equality has remained largely centred around distributive-equality. Successive governments, at the Centre and in the states, have attempted to address the problem of inequality by increasing the scope of reservations. Relying on an approach of distributive-equality for more than 70 years, India has significantly remedied the historical injustices meted out to a sizeable segment of society. However, meaningful equality is still a dream. The depressed classes, in spite of receiving the benefits of reservations, are still treated with contempt.

This is on account of the non-recognition of status-equality as being complementary to distributive-equality. Status-equality is assured through anti-discrimination laws that prohibit differential treatment in terms of caste, gender, age, health conditions and so on. A number of countries have enacted such laws, which adopt a rights-based approach to contain discrimination. The remedies for those who are discriminated against are in the form of compensation or injunctions that restrain such discriminatory conduct.

This is not to suggest that distributive-equality is not important. India’s socio-economic inequality is attributed to its caste system. In 2011-12 upper-caste households had 37 per cent more disposable income than lower-caste households. This translates into better education, nutrition and creation of capital, extending privilege to the upper castes, leading to status inequality. Scrapping distributive-equality is likely to further these cleavages.

Simultaneous recognition of the value of status-equality on a par with distributive-equality is required in India. This would give citizens recourse to a law that provides tangible remedies. A comprehensive anti-discrimination law may well be a necessity.