The Zone is normally quiet. It's only when you return from visiting a metropolis do you realise how quiet it is. When you enter the Zone, vast fields stretch away on both sides of the main road — the ‘Expressway’ — that runs like a spine through the entire length of the territory. Soon, the factories begin to appear, escorting the road for a bit, one after the other. Every now and then, there are roundabouts, with roads branching out to the sides leading to other factories and housing complexes. The plant buildings are all modern, most of them spanking new, as though the things being produced inside leave no marks on anything, as though the products float through the sheds accruing components and make themselves, before lining up in orderly rows outside the buildings to wait for the big transport trucks to take them away. The low, sprawling buildings are adorned by names, both well-known international brands and obscure, serious-sounding ones, automobiles, air-conditioners, electrical parts, biscuits, engineering equipment, all make their presence felt with low-profile, unshowy authority; there are no neon signs and no billboards — everything that needs to be sold has already been sold elsewhere, a lot of it even before it is manufactured, and there is no need for any noise, aural or visual.

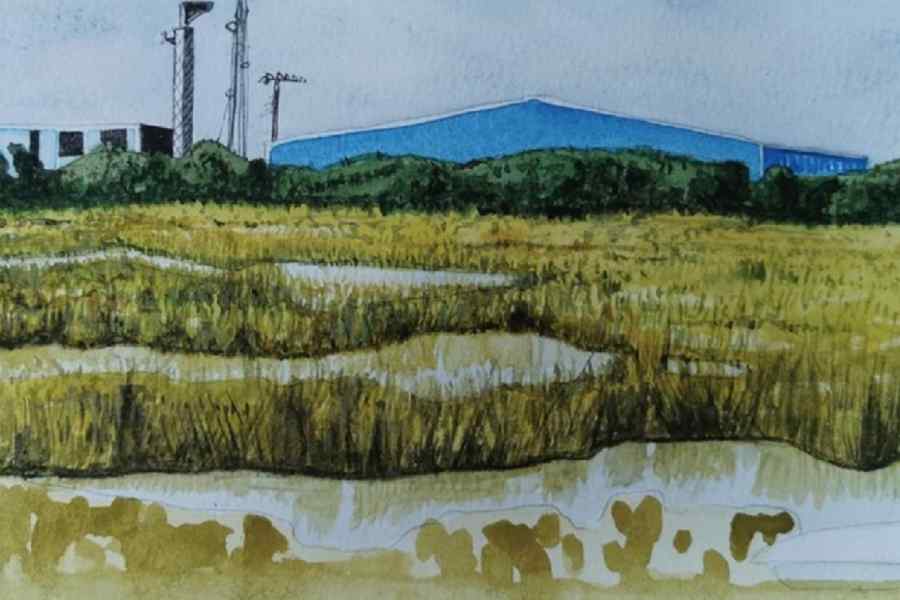

The industry stands in single factory islands and clusters, surrounded by fields and water bodies. Cows wander the scrubland, goats eat grass, cranes put white punctuation marks on sheets of water, other birds flit between the trees, and if you switch off your engine you can hear many different bird calls. Here and there you see a few farmers tending crops but most of the land is uncultivated, waiting for yet another factory to sprout. A few kilometres to the east of the Zone, at the edge of the sea, space rockets blast off from time to time, terrifying the birdlife settled on the big coastal lake, perhaps messing up the avian radar for days.

In the Zone, there is no temple. You take the bus, or the scooter, or one of the company’s people carriers to your daily shrine and you pray all day to the levers and buttons you are being paid to operate. At the end of the day, you go back home, to your local village, to the small flat in the tiny highway town which you share with two others, to your anonymous hotel room with its TV screen or to the manager-level room reserved for you in the 3-star resort in the middle of nowhere, and you enjoy, briefly, the fruits of your daily prayer: you eat, you watch TV, you call your family who live far away, you try and sleep. The next morning, you are back to doing the repetitive aarti with your computer mouse, the looped puja with the gear levers of your forklift. You understand that in the Zone there can be no other temple to compete with that to which you must actually pray — the efficiently running production line.

There is a temple just outside the Zone — you can see it in the distance, poking over the tree line, a fantastical space-age replica of some exotic Far Pavilion as imagined by the cover designer of a best-selling popular novel, shallow stalactites of white poking into the dirty, light blue sky. So near yet actually quite far, so near yet actually not accessible to just anyone, just over there, but only open to members of the Swami's cult. Inside the Zone, there are other exclusive spaces, restaurants serving exotic food of the countries from where the top foreign executives come. Some are closed clubs, others are multi-cuisine and customer-agnostic, where people of all races can mix. There are very few restaurants at the moment but more will come up shortly.

From the chocolate factory comes the smell of industrial milk chocolate, strictly untouched by human hands. From the factory owned by an internationally famous brand comes the smell of roasting coffee. One factory has several hundred brand new cars parked in the lot outside its building. Outside another factory, there is a small forest of newly birthed earth-movers, bright green ones, made to compete with the ubiquitous yellow ones you see everywhere. To what new and innovatively cruel uses will these be put? You can see these machines as an orderly grove of metal or as ranks of rookie soldiers parading at their training camp, about to be unleashed on a defenceless population.

You can’t imagine a labour union in the Zone — there is no place to gather outside the factory gates. There is no place where a small car or tempo could circle outside the factory walls, sending exhortations to the workers through a loudspeaker. Forget the factory perimeters, union organisers wouldn’t even get into the Zone past the security guards and the police in their patrol cars.

The Zone is neat and tidy, quiet and orderly. Once you spend some time inside it, you realise that this is about the unquestioned notion of ‘growth’; this is the ideal India that every major political party wants, except each wants to put its own imprimatur on this industrial paradise, this brand-nursery; this is the collective fantasy of the entire political class of the country, regardless of ideology or ethnic or cultural loyalties.

In the Zone, there is no temple. Perhaps the Zone itself is the temple. Or perhaps all the new temples coming up outside are actually worship-stations for the Zone.