Like ‘semi-final’ election, the term ‘wake-up call’ is much overused in Indian political discourse. Last Tuesday, as the painfully slow counting process yielded the outcome of the five assembly elections and left the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party shell-shocked, the more cautious among analysts were inclined to limit the fallout of the BJP’s setback and the Congress’ spectacular recovery. It was, they felt, a jolt to the Narendra Modi government but not necessarily one that would definitely ensure a change of government at the Centre in May 2019. In short, it was the proverbial wake-up call.

The more optimistic in the BJP saw a silver lining in the unexpected defeats. Another round of victories, they rationalised, would have infected the party with insufferable arrogance and complacency in the few months before the general election got under way. They pointed to the smugness that had gripped the organisation after the three victories in Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh in December 2003, an over-confidence that propelled the leadership to advance the date of the general election by six months. The expectation of inevitable victory against a shambolic Opposition led to major tactical miscalculations, indifferent campaigning and even a lower turnout of the committed voters in 2004 and cost Atal Bihari Vajpayee a second term. The belief is that after Tuesday’s defeats, the party leadership will be more circumspect, more sensitive to stirrings on the ground and leave nothing to chance.

To some extent, the wake-up call theory is not pure wishful thinking. Ever since the mahagathbandhan of the Rashtriya Janata Dal, Janata Dal (United) and Congress trounced the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance in the Bihar assembly election of 2015, the BJP has become more alert to the possibility that banking on the vagaries of the first-past-the-post system was insufficient. The party had to expand its support base to survive the likely unity of all forces that perceived Modi’s rise as a threat to their very existence. The percolation of the BJP down the social ladder was in evidence during the Uttar Pradesh election in early-2017 and yielded handsome returns. Even in the recently-concluded assembly election, the BJP did make a concerted bid to reach voters outside the saffron fold. The outreach was based on bringing together beneficiaries of state and Central government welfare schemes.

Why did this approach falter?

It is now sufficiently clear that the BJP seriously underestimated the political consequences of the fall in agricultural incomes. It is not that the problem bypassed the attention of the decision makers. The state governments in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh were quite prompt in raising the minimum support price for agricultural produce. However, the increase in Chhattisgarh was perceived to be grossly inadequate and the payment of differential in Madhya Pradesh could not include all the produce farmers had to sell. In such a situation, the unrelenting focus of the Congress president, Rahul Gandhi, on the diminishing real income of farmers had a marked impact.

The most dramatic effect was felt in Chhattisgarh. Gandhi’s announcement at a campaign rally in the state shortly before the second phase of polling of a hike in the MSP to Rs 2,500 per quintal and a complete loan waiver within 10 days of the Congress forming the state government had an electrifying effect. At one stroke it nullified the appeal of all the welfare schemes of the Raman Singh government and led to the decimation of the BJP in the rural areas. The BJP vote fell dramatically from 41.04 per cent in 2013 to 32.9 per cent.

The rural swing in Chhattisgarh had a knock-on effect in the urban clusters. The demonetisation of November 2016 and the subsequent introduction of the goods and services tax had unsettled the BJP’s core support base of small traders, accustomed to operating in a twilight zone between the formal and informal economy. The resentment had been in evidence during the UP and Gujarat assembly elections but the party had somehow managed the disquiet. In Chhattisgarh, however, the Congress managed to tap the anger and cream off enough of the BJP’s core vote to make a visible difference. Survey reports from Rajasthan also suggest that the BJP’s solid vote among the upper castes was affected, also presumably by the GST.

It was significant that ‘small shopkeepers’ were among the people Rahul Gandhi thanked profusely at his press conference in Delhi on Tuesday evening after the declaration of results.

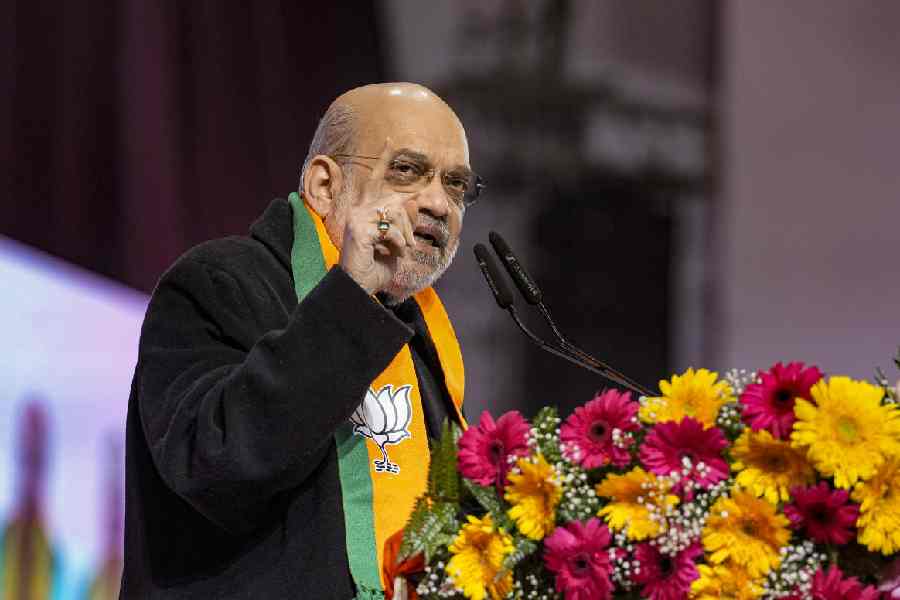

That there would be a political price to pay for GST was known by the BJP top brass since its introduction in 2017. However, after Amit Shah inveigled the party out of a difficult situation in places such as Surat during the assembly elections, there was a belief that the crisis had been averted. It obviously hadn’t. The question is: was this a one time protest vote by disaffected traders who will now return to the parent fold for the general election?

My feeling is that the BJP will have to travel the extra mile to address the grievances of both farmers and traders. As of now, the Modi government has shied away from populist sops such as loan waivers and tried to address the question of farm incomes with a long-term, systemic approach. However, the instant appeal of Rahul Gandhi’s fiscally imprudent but politically rewarding sops has put inordinate pressure on the Modi government to do something similar. So far the prime minister — always impatient with patchwork solutions that skirt the roots of the problem — has resisted pressures. But with the Congress’s populism striking a responsive chord, he may have to compromise. Martyrdom for the sake of principles is never popular in democratic politics.

The issue is not merely centred on the quality of governance. Fiscal responsibility is undoubtedly a lofty ideal that has earned the Modi government praise from investors and other custodians of global capital. Unfortunately, it is not a very popular approach and very difficult to sell politically — and not merely in India. Being tough and steadfast has its own attractions but there is also a real danger that the tough-guy image may get to be equated with a lack of caring and compassion. Modi could perhaps do with some fine-tuning of his image.

The latest round of assembly elections have undermined the BJP’s self-confidence, but only partially. The belief that Modi’s personal appeal is still firmly intact continues to drive the BJP, just as it rallies his opponents to cling together for self-preservation. There is, for example, a general consensus that had it not been for Modi’s spirited rallies, the outcome in Rajasthan would have been far worse for the BJP. Modi couldn’t prevent a defeat but he warded off a rout. In all the three states, the BJP will live to fight hard and reclaim lost ground in 2019.

Yet, these election results have shown that in invoking agricultural distress and limited opportunities for organised employment, Rahul Gandhi has managed an unexpected response. Some would argue that the experience has even turned an entitled dynast into a real political leader, capable of exercising informed decisions. Unless Modi responds, as people expect him, he may end up nullifying the possibility of the 2019 general election being fought as a quasi-presidential contest. If, instead of stability and leadership, local grievances occupy centre-stage, the anti-BJP forces will have the upper hand. In that case, the 2014 promise of achchhe din may come to haunt the BJP next year.