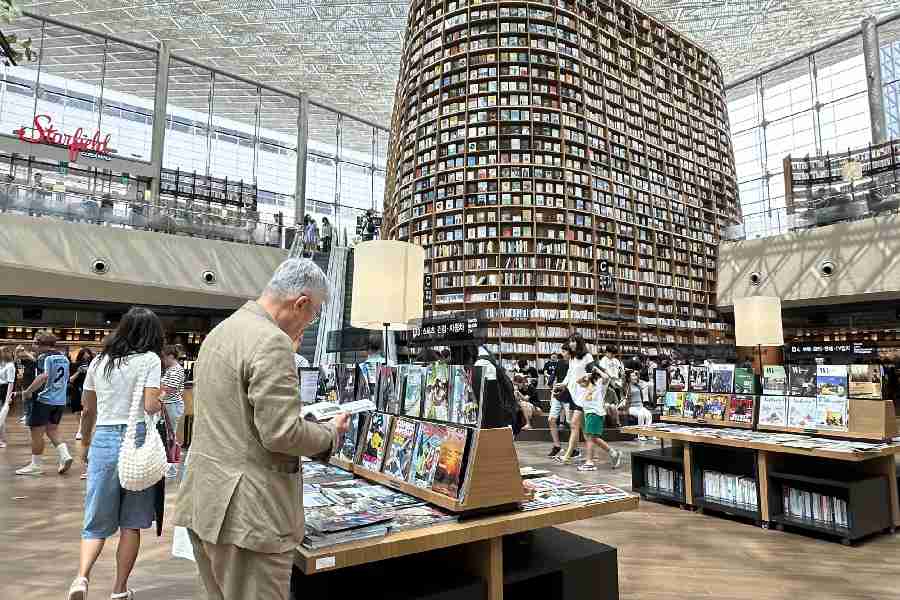

Where the mind is without fear and knowledge is free — public libraries are emblematic of this sort of freedom. Even in the age of the internet, when information is available at the fingertips, accessibility to knowledge may not be egalitarian or affordable. This is because evolving technologies may be expensive for those on the margins; the elderly may also find them difficult to navigate. A free public library, on the other hand, is a space that is open to all regardless of social or economic background. In a country like India, with a long history of gatekeeping knowledge and systemically excluding specific communities from reading and learning because they belong to the ‘wrong’ caste or gender, free public libraries can democratise knowledge in the truest sense. It is in this context that the work being done by the Free Libraries Network, a collective of more than 250 libraries around South Asia, assumes importance. The FLN recently released a policy memo, The People’s National Library Policy 2024, drawn from its years of activism at the grass-roots level, which can be instructive in India where libraries, in spite of their challenges, continue to serve as the gateway to reading and learning.

Public libraries are a state subject in India. Data from the Union government show that of a total of 27,671 government-run libraries in India, only 7,836 exist outside southern states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. The fact that this geographical imbalance echoes state-wise literacy rates is instructive. Most of these public libraries are also not free, even when state laws mandate them to be so. A library cess, derived from state revenue taxes, pays for the upkeep of public libraries: in other words, taxpayers fund them as well as pay to use their services. To achieve equitable access to knowledge as envisaged by the National Policy on Library and Information System in 1986 — this draft, though, was never ratified into policy — public libraries must be free from any kind of fee, be it for membership, penalty, or services like the use of the internet.

But at a time when states face severe fund crunches — is the strain on federalism to blame? — libraries are increasingly experiencing cuts in budgets or, worse, shutting

their doors. The Union government, when it does get involved, is often misguided in its efforts. The National Mission on Libraries came into being in 2014 under the Union ministry of culture to revive and modernise public libraries. But the lion’s share of its budget has been spent on creating digital libraries, including the National Digital Library of India, which barely makes a ripple in a country with embedded digital inequity.

Encouragingly, the void left by public libraries — the result of policy myopia — is often filled by community libraries, started mostly by non-governmental organisations or locals — the FLN is one such network — that are open to all. These are thriving spaces with active membership because the agenda transcends reading: for instance, their library programming and practices envisage adult education initiatives and storytelling sessions for children across caste, class and gender. Sustaining such community initiatives remains the key. The challenge must be answered to. A well-informed citizenry is integral to a healthy democracy.