Yogendra Yadav’s two recent articles in The Indian Express have initiated an interesting public discussion on the relevance and the future trajectory of what may be called Indian political theory. Yadav highlights a set of issues — an “… emaciation of our political vision, the shrinkage in the vocabulary of politics, the withering away of our political understanding, the poverty of political judgement and the recession in the agenda for political action” — to conclude that “[t]he river of ideas… has suddenly dried up.” This critical assessment of contemporary political thinking has led to a highly sophisticated and nuanced debate.

A section of scholars, especially political scientists, argues that academic analysis of Indian politics — critical mapping of political phenomena in their entirety, their logical explanations and appraisal, and the exploration of the avenues where new forms of politics get shaped and nurtured — cannot be underestimated. Indian political theory, it is claimed, is a rich subfield of political science, which is flourishing in a variety of ways.

Yadav acknowledges this line of argument in his rejoinder. He also admits the political value of scholarly interventions. However, Yadav further clarifies the fact that his primary purpose is to investigate the reasons that led to the decline of imaginative political thinking in India over the years. More precisely, he emphasises the need to have a “collective deliberation on why we reached this place, and what can be done to reinvigorate this lifeline of our republic.” This is an important question.

While it is true that contemporary Indian politics is being studied and analysed as a serious object of academic research, the relationship between political analysis and political action (at least in the narrower sense of the term) is almost insubstantial. Political parties do not engage with the intellectual class. There are intellectual wings in most national parties which often function in collaboration with affiliated organisations, especially in universities. However, these bodies do not function as independent think tanks; instead, these intellectual wings are used to capture academic institutions for establishing political dominance. The party intellectuals thus behave like official spokespersons simply to disseminate the message of the top leadership. That is one of the reasons why professional academics do not want to be associated with such intellectual wings.

It is important to remember that our democracy has become highly election-centric. Political parties envisage elections as the main arena of competitive politics. The big ideas, such as social transformation, imagination of an egalitarian society, establishment of a just economic system, are, consequentially, reduced to proposed policy initiatives. The election process has been transformed into a political marketplace to address voters as consumers. This framework forces the political elite to look out for ready-to-use, bullet-point responses, which might be used for making electoral packages more appealing and effectual. This, in turn, reduces the possibility of a long term and sustainable political engagement with the intellectual class. At the same time, it provides the political class the confidence to rely on a business-like imagination of actual politics. The success of the idea of winnability in election is a good example in this regard.

There are, however, a set of scholars who try to bridge the gap between intellectual work and political life of the country. A long list of intellectuals — Ashutosh Varshney, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, Suhas Palshikar, Sandeep Shastri, Suraj Yengde, Harish Wankhede, Christophe Jaffrelot, Ramachandra Guha, Sanjay Kumar, Mukul Kesavan, Abhay Dubey, Ashok Pandey, Peter R. deSouza, Zoya Hasan, Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, Nivedita Menon, Nandini Sundar, Rama Lakshmi, Asim Ali, Yogendra Yadav and many others — contributes significantly to shape the nature of public debates in India.

Yogendra Yadav’s intervention, in this sense, is more relevant. It recognises the separation between professional academic research and the actual business of politics; yet, at the same time, he calls upon the observers, analysts, and practitioners of politics to collectively think and produce futuristic imaginations of politics in the Indian context.

There are two important issues, which require serious attention to understand Yadav’s rather provocative observation about the decline of political thinking. First, there is an invitation to discover a deep politics of comprehensive social change. Yadav’s recent writings underline a crucial distinction between shallow politics (which sticks to a particular identity as the ultimate vantage point for political action) and deep politics (a profound, multilayered, nuanced form of politics, which gives due recognition to uncomfortable facts and internal contradictions). The public debate on Muslim identity is a good example to elucidate this distinction.

Hindutva politics relies heavily on a homogeneous and undifferentiated Muslim identity to sustain the Hindu-Muslim divide. This has helped it project every aspect of Muslim social life as a problematic phenomenon. The opponents of Hindutva have questioned this obvious demonisation of Muslims. They evoke secular, democratic values of the Constitution to refute all kinds of communalism. No one can deny the significance of this egalitarian-democratic form of politics. However, the problem arises when the internal contradictions among Muslims — caste-based exclusion of Dalit and Pasmanda Muslims and the marginalisation of Muslim women — are projected as unimportant, troublesome and Hindutva-sponsored issues. From Yadav’s point of view, this strategic silence on internal contradictions may be described as the shallow politics of identity, which would eventually contribute to a totalising framework promoted by the Hindutva groups in the name of nationalism.

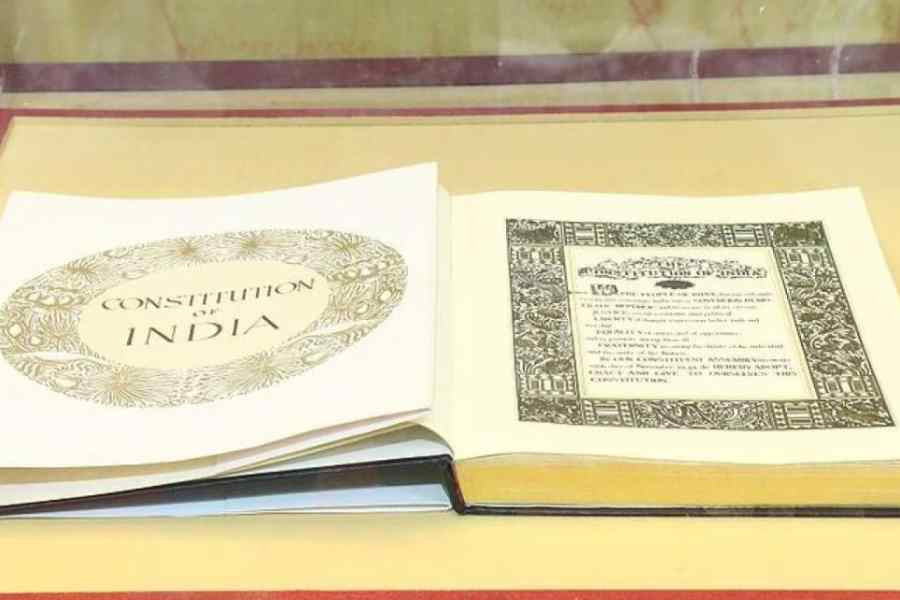

This brings us to the second facet of Yadav’s argument. He claims that the national movement was an intellectual resource, which played a significant role in the making of the Constitution. Postcolonial Indian politics, especially in the early decades after Independence, inherited the values and ideals of the national movement. The Constitution, in this sense, is not merely a legal document; it is a political manifesto, which encourages us to get involved in the egalitarian politics of human emancipation and socio-economic equality. In other words, the Constitution is a legitimate resource for us to produce new and more radical imaginations of social change. This proposal, in my view, goes beyond the two given narratives of our times — the Constitution is a sacred book, which must always be obeyed as a legal directive and the Constitution is under threat and, hence, it must be protected. Yadav’s thesis wants us to have a new kind of political vision, which might help us produce new ideas of India. The present debate, it seems, is certainly contributing in this direction.

Hilal Ahmed is Associate Professor, CSDS, New Delhi