The birth of the ‘INDIA’ coalition this week marks the first major attempt by the Opposition parties to reclaim the space of nationalism from the Bharatiya Janata Party. Over the last decade, the ruling party has instrumentalised its plank of nationalism to corrode the political culture and the institutions undergirding the country’s democracy. The twenty-six party INDIA coalition has finally screamed out the obvious in one voice: India’s plural democracy is what has shaped the distinctive character of our nation post independence. Thus, to undermine democracy is to violate an essential part of our shared nationhood.

At the time of India’s independence, the country’s political elite faced an almost insuperable dilemma. Few expected India to survive for long as a democratic nation-state. This was because the logic of nation-building and the logic of democratisation seemed to be ranged in opposite directions.

Briefly, India had little elbow-room to follow the classic nation-state model of Europe where cultural homogeneity is imposed from above in order to construct a nation matching the territorial borders of the State. This was partly because of the country’s rich diversity: less than 40% people spoke Hindi, a presumed link-language, and nine Indian languages commanded more than ten million speakers. Furthermore, ethnic/linguistic subnationalism (such as in Tamil Nadu and then Assam) had already become activated prior to the foundation of the State. Thus, India could be seen to be a multi-national State, prone to threats of secession with the onset of competitive politics.

According to an influential work, Crafting State-Nations: India and Other Multinational Democracies, by the scholars, Alfred Stepan, Juan J. Linz and Yogendra Yadav, India represented the only non-Western country to have developed a successful model of multi-national federal democracy. The authors trace the success of Indian democracy to its distinctive approach of fomenting a shared feeling of belonging, of a shared nationhood, among its diverse population. By abjuring the coercive policies of a standard ‘nation-state’ model and embracing the democratising and accommodative policies of a ‘state-nation’ model, the Indian Union built a crucial reservoir of legitimacy. These policies included asymmetrical federalism, the combination of individual and group rights, and a parliamentary system.

The state-nation model proved successful in integrating different ethnic/linguistic minorities precisely because it did not impose any one singular identity; rather it allowed the citizens to hold and express multiple identities. The cross-cutting nature of these identities (such as language, caste and ethnicity) ensured the stability of the federal structure and incentivised regional parties to pursue a moderate agenda.

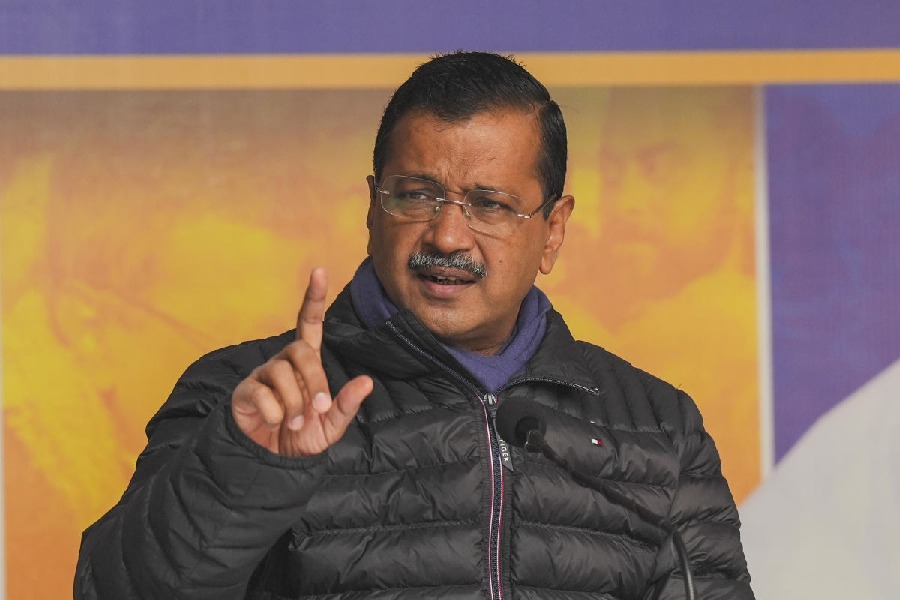

The twenty-six parties assembled in Bengaluru have implicitly presented themselves as the legatees of this pluralistic approach to nation-building. They compete with the ruling party, the BJP, which champions an ethno-majoritarian model of nation-building (Hindu rashtra). At the level of the State, the BJP seeks to construct or remould ethnocracies, typically by excluding certain ethnic/religious minorities.

Can the old pluralist conception of nation-building then match up to the prevailing ethno-majoritarian conception?

Not unless the former rediscovers its umbilical connection with progressive democratisation. After all, the democratising promise of the state-nation model has not quite been able to make its presence felt at the level of subnational states. In many such states, the process of democratisation sputtered to a halt by the 1990s as dominant elite groups closed ranks to maintain control of State resources and thwart the upward mobility of newly-mobilising groups. In Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, the near ownership of the Mandal agenda by middle-peasant castes like Yadavs and Kurmis considerably weakened its emancipatory potential.

Let us take the case of Assam. The reason Assamese nationalism allowed itself to be subsumed by ethnic Hindu nationalism flowed from the incentives of the dominant Assamese middle class. The Congress regime of Tarun Gogoi had become overdependent on patronage structures rather than providing substantive representation. Thus, the Congress, operating under the plank of Assamese subnationalism, struggled to accommodate newly-mobilised groups of tea tribes or even to retain the loyalty of the Bengali Muslim minority. For the Assamese middle class, continuing dominance thus required a new legitimating framework, which was readily provided by Hindu majoritarianism, allowing for a grand alliance between Assamese Hindus and Bengali Hindus. A similar ethnocratic solution was provided by the BJP in Manipur, allowing Meitei elites to legitimise their leadership of the state using the discourse of Hindutva.

In both Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh, the BJP has succeeded in incubating a new ‘Hindu’ popular sovereignty, marrying together upper castes and sections of OBCs into a dominant coalition. In both the states, the Opposition parties failed to mobilise the fractious group of non-dominant OBC castes, or to reform the structure of the political economy. The BJP’s Hindu majoritarian model feasts on the decaying structures of elite control, whether based on caste networks or linguistic identity, replacing them with a refurbished system of elite domination. In contrast, the BJP has been unable to penetrate states such as Kerala and Andhra Pradesh where the political economy is structured along more egalitarian lines. Similarly, in Karnataka, the BJP seemed to have lost political space through an over-reliance on the ethno-majoritarian model.

These case studies demonstrate that the most effective check against an ethno-majoritarian Hindu domination is the devolution of power towards previously marginalised social groups, ensuring their stake in the democratic system.

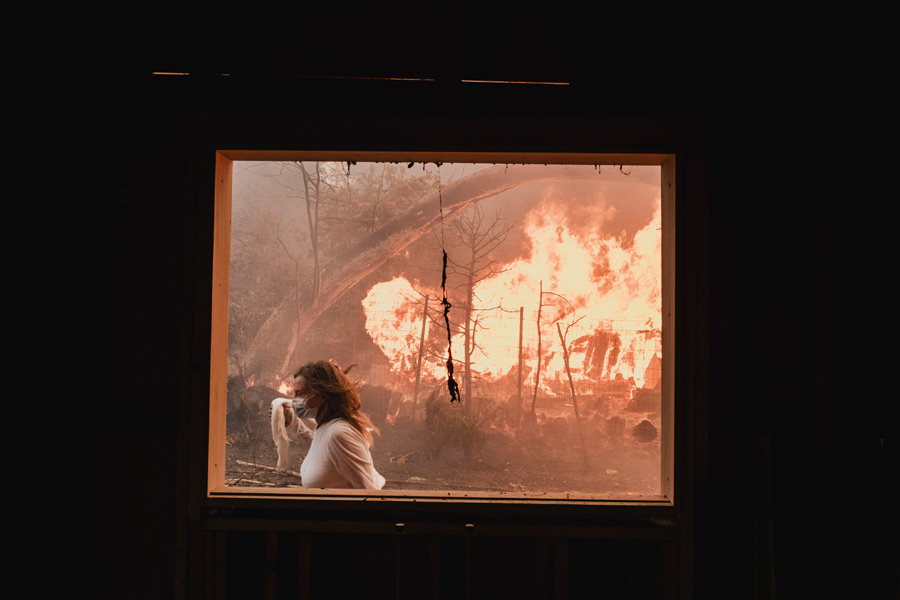

The serious threat facing Indian democracy has manifested quite clearly in the state of Manipur. The ethno-majoritarian approach of the BJP flattens the cross-cutting cleavages of caste, tribe and language that facilitate political balancing and peaceful resolutions. Instead, ethno-majoritarianism reduces socio-economic conflicts to a singular lens of an irreconcilable minority-majority dynamic, thus carrying the potential for explosive violence.

However, an alternative model of nation-building cannot merely appear to be a clever draping over an earlier status-quo. It must go beyond the old ‘state-nation’ paradigm and offer a new model of democratisation that is not only inclusive but also promises substantive material change at the grassroots.

Asim Ali is a political researcher and columnist