A question that almost every singer not connected to the film world is asked is this: “Have you sung in the movies?” If your response is in the negative, then “Why? Are you against singing in the movies?” follows. If you say that you have not got the right opportunity, some will advise you on how your art will reach many more people. Artists from the folk tradition probably face more of this line of questioning than others because of the lesser visibility their art receives. If the musicians respond that they are fine with where they are and what they do as artists, then — depending on the kind of music they practise — their attitude is construed as an example of either snootiness or a lack of initiative and imagination.

On the surface, these queries seem to come from curiosity. But at the bottom is that one craving that all of us have: the need to be famous or being associated with fame. Closely linked to this is the common definition of success. In the movie, The Disciple, directed by Chaitanya Tamhane, even the puritanical classical musician has a voyeuristic relationship with reality shows and Bollywood. He hopes for a way by which he can remain ‘pure’ yet receive the same kind of adulation that the playback singer gets. This is an urge that often makes us lose balance and deprives us of the ability to think clearly. The famous and the nobody are not two distinct categories. The fame hierarchy is graded, each segment trying to keep those below just where they are and members of every layer aspiring to reach the one above. There is always someone more important than yourself.

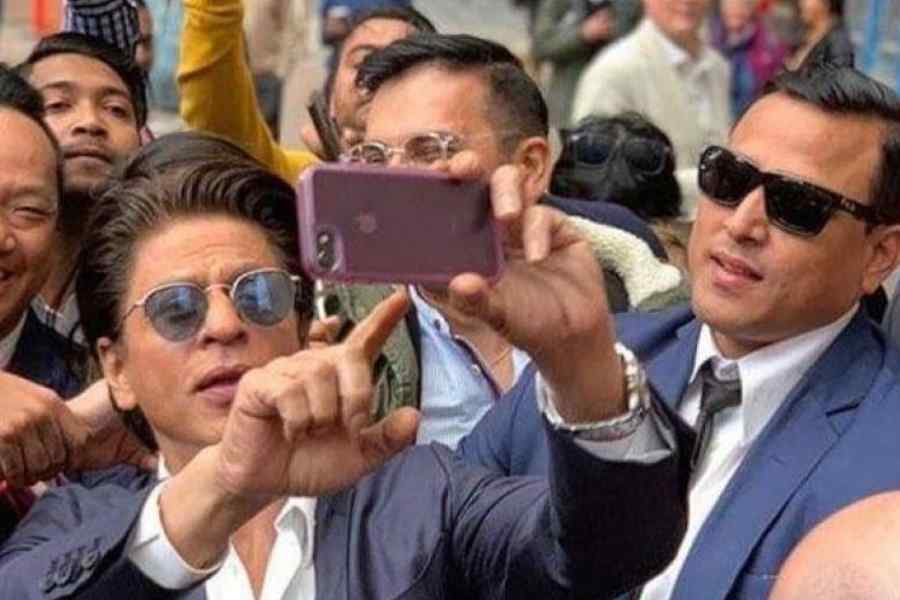

While watching some of the World Cup matches in the stadium, I noticed exactly the same madness at play. Sourav Ganguly peeped out of his special box at the Eden Gardens and those in my stand went wild. Selfies were being taken even though Ganguly was doing his own thing. Spectators constantly called on the cricketers on the boundary lines to wave or smile. The mobile phone is a convenient aid for this purpose, allowing a person who is some distance away to zoom in on selfie mode, take a picture and share the same with friends. These yearnings cut across class. It did not matter whether the person was rich or poor; the fascination for the famous is universal. This is not unique to any specific culture. The various categories of famous-ness differ in each culture, but the urge and the obsession are universal.

But why is this even a problem? Wanting to be known is not necessarily a bad thing. Some will argue that it makes individuals work harder and fulfil their dreams. These are partially true, but we cannot ignore the serious social, economic and psychological problems fame fanaticism creates.

Dominant fame narratives trigger homogeneous yearnings at many levels. In art, for example, there is an aesthetic urge to give all art forms a cinematic feel. The reason is simple: cater to what is popular! The artist, in search for the same stardom that cinema generates, forgets that there is a fine balance that needs to be struck between the aesthetic and the commercial. Also, the commercial that the artist seeks does not come from an artistic depth; it is mindless populism. This means that in the long run, a certain distinctiveness is lost. We see something similar in our social media behaviour. The fame of influencers has captivated all of us and we want to style ourselves like them. The same is true of how we conduct even our weddings today. There is rarely a wedding without the influence of the* Bollywood model. Even within a certain field of functioning, the famous modulate behaviour. Which sub-specialisation becomes attractive depends not only on financial viability but also on the sexiness of visibility.

There is a direct economic impact of such a fame-based chassis. The fame of one profession or a large number of the famous emerging from just a few workspaces results in the over-prioritising of those occupations. Cricket is a great example of that problem. When I told my trainer that I was going to the World Cup matches, she spoke about how athletics is completely ignored. In fact, athletes are not even viewed as sportspersons. As far as society is concerned, ‘they run’. This would be true of so many other sports. The counter-argument would be that of market economics and the inevitable nature of demand and supply. But all of us know that neither demand nor supply is a benign functionality. This vicious cycle can never be broken unless we recognise that we are all intoxicated with attention. As a society, we need to disrupt that compulsive habit. It is so ingrained that one star from a tertiary occupation cannot break the cycle. We need collective, corrective action. Mechanisms of society that control our behaviour, including the political establishment, financial institutions, social networks and media, have to change.

Within a highly discriminative social structure where the mapping among caste, occupation and wealth are correlative, jobs done by those lower in the hierarchy are rarely discussed and the individuals ignored. Caste itself is vertically-structured fame listing. The pride associated with castes clearly demonstrates this phenomenon. A Brahmin, Bania or Rajput will never feel embarrassed about proclaiming his caste, speaking publicly about caste’s greatness and using it as a last name. But as you go down the hierarchy, the need to hide caste identity becomes necessary. So much so that even the famous from an oppressed section will disassociate themselves from their caste once they find place on the higher seats. This means a driver, civic worker, nurse or waiter can never be truly respected in our society. People doing these jobs can never become famous. To become famous, they have to mimic accepted fame-caste prototypes.

The psychological impact of this obsession, especially on younger people, also needs to be considered. Exceptions aside, parents and friends direct the attention of children towards success stories that hit the headlines. Public knowledge of a great deal of wealth is also fame. The social pressure on children to imitate the famous in the choices they make is enormous. In this frantic mode for notability of some sort, we forget to teach our children human values. We want the fame-success combination for them and inculcate in them that ‘win at any cost’ attitude. Our schools are no different. They are places where children learn to vanquish the weak. The weak are told they will be irrelevant. Life is not about receiving from nature, making true friends, taking care of oneself or caring for people. It is about winning that famous trophy.

Some readers may think this entire column is hypocritical because it comes from a person of privilege, who has some degree of wealth and fame. This is entirely true. But even as a successful individual, I need to acknowledge the flaws in my way of living. I am not here to tell the underprivileged that they should not aspire. Much like how we correctly expect developed countries to take more responsibility for the climate change crisis, people like us should reflect on the fame-obsessive framework we create and perpetuate, take responsibility for this ugly model, and be the first to change. We do have a social crisis on our hands.

T.M. Krishna is a leading Indian musician and a prominent public intellectual