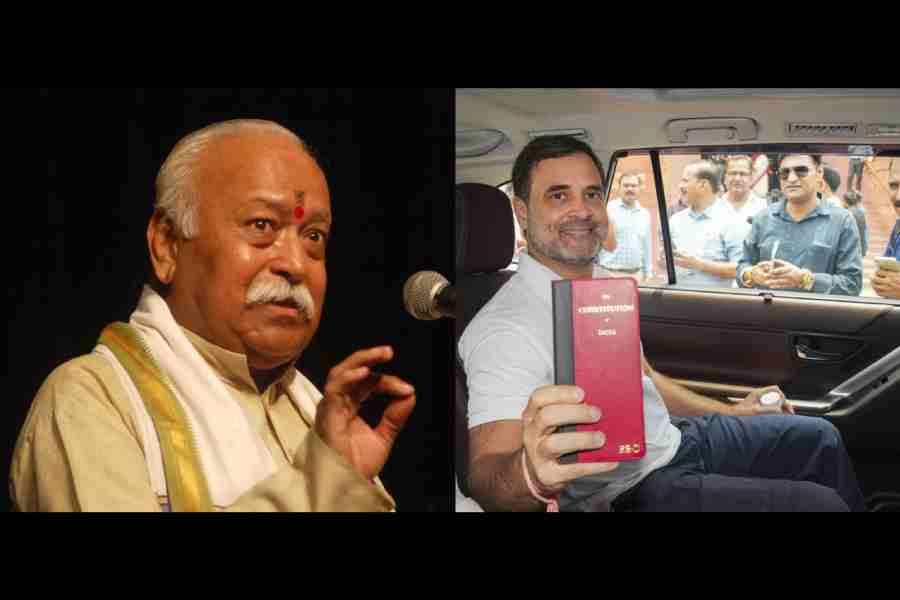

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh chief, Mohan Bhagwat, claimed this week that India achieved its “true independence” on the day of the Ram mandir’s consecration in Ayodhya. Bhagwat was careful not to reject the Constitution but only repudiate its mode of implementation in post-Independence India.

“After India got political independence from the British on August 15, 1947, a written Constitution was made according to the path shown by that specific vision, which comes out of the ‘self’ of the country, but the document was not run according to the spirit of the vision at that time,” said Bhagwat a fortnight before India celebrates its 76th Republic Day.

This was an advance from the RSS’s earlier aversion to the constitutional structure itself, which it derided as a foreign import. That position had been explained by Bhagwat’s predecessor, M.S. Golwalkar, and was explained in Bunch of Thoughts. “Our Constitution too is just a cumbersome and heterogeneous piecing together of various articles from various Constitutions of Western countries. It has absolutely nothing which can be called our own. Is there a single word of reference in its guiding principles as to what our national mission is and what our keynote in life is?”

To understand the RSS’s ambivalent acceptance of the Constitution, we must first ask a basic question. What is the importance of the Indian Constitution? That question can be answered in two ways.

The first answer is that the Constitution is important because it provides the architecture of rules defining the functioning of democratic institutions. In other words, the importance of our written Constitution lies in the checks and balances it mandates, preventing the accumulation of undue authority in any one institution (primarily meant to constrain the executive).

The second answer is that the Constitution is important because it is a set of guiding principles and values, a charter which defines our nationhood. The ‘sacred’ nature of the Constitution, therefore, does not derive from juridical minutiae but from these guiding principles that encapsulate the spirit of our freedom struggle and represent the product of a considered negotiation among our founding leaders hailing from diverse ethnic/caste, religious and linguistic backgrounds.

Our argument regarding the importance of the Constitution derives from its second aspect. The historian, Perry Anderson, wrote that the Indian Constitution “owed the majority of its provisions to Westminster: some 250 out of its 395 articles were taken word for word from the Government of India Act passed by the Baldwin cabinet in 1935”. The colonial inheritance of the Constitution lies in its scheme of dividing powers among the governing institutions, which lent a formidable centralising bias.

But what makes the Constitution distinctive from the Government of India Act were the chapters on Fundamental Rights and the Directive Principles of State Policy. The commitment to a ‘bill of rights’ goes back to the Nehru Report of 1928. The inclusion of Fundamental Rights was later supported by B.R. Ambedkar, much like the inclusion of the Directive Principles was pushed by the Gandhian and the socialist members of the assembly. Therefore, these parts embody the egalitarian and anti-colonial philosophy of the Constitution, articulating the guiding principles of liberty, equality and fraternity.

Now let us come to the aforementioned comments of Bhagwat and Golwalkar. Unlike the impression conveyed in Bhagwat’s statement, the RSS embraces the Constitution only as a technocratic framework of governance (the first aspect), as it now controls the commanding levers of governance, but rejects its distinctive spirit (the second aspect). And unlike the statement of Golwalkar, the Constitution does provide ‘guiding principles’ which define the ‘national mission’ in the form of Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles, as we have just noted.

It is this superimposing framework which makes the Constitution a charter that defines our nationhood. The RSS defines Indian nationhood in terms of a (Hindu) civilisational legacy. This is, in fact, now the position of the Central government whose leaders (such as Narendra Modi and S. Jaishankar) routinely present India as a ‘civilisational State’.

Why do we say that ‘India as a constitutional State’ and ‘India as a civilisational State’ represent two competing modes of defining Indian nationhood?

One of the leading scholars of nationalism, Craig Calhoun, defined nationalism as a discourse containing a framework for making and evaluating claims as well as for mobilising people around collective projects. “[N]ations are constituted largely by the claims [they make for] themselves, by the way of talking and thinking and acting that relies on these sorts of claims to produce collective identity, to mobilize people for collective projects, and to evaluate peoples and practices.”

Using this definition, let us delineate the contradictions between constitutional nationalism and civilisational nationalism.

In the former framework, people make claims based on their citizenship rights guaranteed by the Constitution. In the latter framework, claims are made based on the ‘desire’ and ‘feelings’ of Hindu subjects, as formulated by Hindu religious/political groups, and their interpretation of the ethos of Hindu civilisation.

From the former springs the claim of Muslims or Dalits or women to eat, pray, dress, and marry whomever they want. And from the latter springs the claim of right-wing vigilantes to restrict their freedoms because, in their subjective evaluation, it violates the ethos of Indian civilisation. In a civilisational State, the legitimacy and the ethical value of these competing claims would be judged altogether differently than in the case of a constitutional State, as we have seen over the last decade.

Every nationalism is a cultural construct based on a quest for justice around which elites mobilise the population and strive to create a cohesive sense of national identity and solidarity. Indeed, this quest for justice lies at the heart of the idea of India as a constitutional State as well as a civilisational State. But the meaning of justice is starkly different, even opposed. The former defines justice as ‘social, economic and political’ (as mentioned in the Preamble) while the latter defines justice in terms of the redemption of the Hindu civilisation and the reclamation of its ‘lost glory’. While the former speaks of guaranteeing the citizens ‘equality of status and opportunity’, the latter speaks of exalting the ‘native’ community to its rightful place after avenging the humiliations of the past.

The present ‘civilisational State’ is paring back the State in terms of economic protections for the working class and the farmers (the new labour codes and proposed farm laws) and social protections for the marginalised (the massive backlogs in filling reserved positions in government). At the same time, it is strengthening the coercive powers of the State (as with the new legal codes, the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita) while inducting vigilante networks as quasi para-State bodies in the functioning of the State, in what Christophe Jaffrelot has termed the Hindutva “deep state”.

In the novel, The Grapes of Wrath, set against the ravages of Depression-era America, John Steinbeck describes the condition of ordinary people: “... and in the eyes of the people there is the failure; and in the eyes of the hungry there is a growing wrath. In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy, growing heavy for the vintage.” This can also be an appropriate descriptor of our national condition where the majority of our people, ravaged by the pandemic, chafe under the yoke of the high cost of living and peak inequality.

Last year, the Supreme Court pronounced that the Constitution intended to bring about a “sense of social transformation” while interpreting the constitutional mandate to distribute the “material resources” of the country in the manner which “subserves the common good” as also inclusive of some forms of “private property”. The challenge to the Hindutva national project would only succeed if it is based on this impulse towards social transformation represented by the Constitution.

Asim Ali is a political researcher and columnist