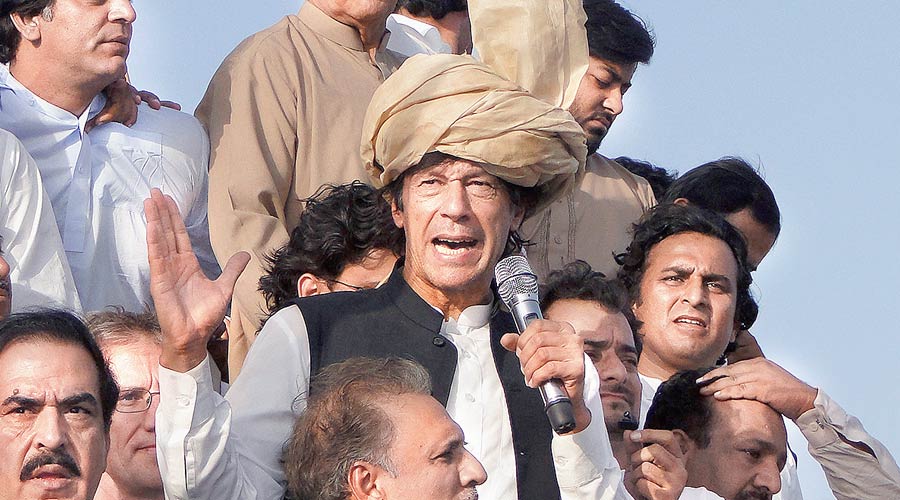

Saturday, April 9, 2022, will go down in sporting annals as the day one of its biggest icons had one of the biggest falls from grace. The ouster of the former cricket superstar, Imran Khan, as prime minister by Pakistan’s Parliament, the National Assembly, in a midnight no-confidence vote after his desperate and feeble attempt to undermine the Constitution and the Supreme Court is a first in a country where volatility comes with any political job. A measure of this volatility can be had from the fact that Liaquat Ali Khan, Pakistan’s first prime minister, remains the person with the longest tenure — a little over four years — in office until his assassination in October 1951.

Before entering politics, Khan had been turned by Pakistan’s people into a cricketing demigod — one of the leading all-rounders of the world, an astute captain with an eye for spotting talent, a leader of men who could hold the fractious dressing room together by the sheer pull of his personality, and the go-getter who led Pakistan to its biggest sporting triumph, the cricket World Cup in 1992. Added to all this were his good looks, charm, Oxford education — even if he passed in the third class — and his reputation as a playboy who mingled with the swish set of London, once even posing for a British newspaper sprawled on a bed clad only in tiny, satin briefs.

But, as he would later admit, he felt empty. Khan began to shun clubs, parties and girlfriends. He went on a mission to build a cancer hospital in Pakistan for the poor in memory of his mother who had died from it. By 1996, the transformation was complete. Khan welcomed the Taliban’s victory in Afghanistan and embraced a conservative brand of Islam. He promised a change from Pakistan’s dynasty-driven politics, monopolized by families such as the Bhuttos and the Sharifs, vowing to fight corruption and usher in reforms. His rhetoric became increasingly anti-American as he sought to portray that the real issue for Pakistan was not extremism but governance.

The image change didn’t always win him supporters — one Pakistani newspaper ridiculed him as ‘Im the Dim’, a tag Khan got during his London days, after his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party drew a blank in the 1997 elections but, as with his cricket, he didn’t give up. By 2010, Khan’s brand of politics gained momentum as his rallies started drawing huge crowds. In the 2013 elections, his party increased its tally in the National Assembly to 35 seats. In 2018, he got the prime minister’s chair after his party won the most number of seats in the elections that followed Nawaz Sharif’s disqualification for the post as he had become enmeshed in a slew of corruption cases. Importantly, Khan was someone the country’s powerful military bosses seemed to think they could work with. Khan shared their worldview, in which Pakistan would be guided less by the United States of America and talk more with the Taliban and other extremist groups.

His first few months were a period of relative stability and Khan did manage to steer the country through the Covid-19 pandemic but his lacklustre response to rapid inflation in recent months fanned public resentment. The once-divided Opposition parties joined forces to instigate a vote of no-confidence and remove Khan’s slender parliamentary majority — a chain of events Khan has insisted, without evidence, as being fomented by a foreign conspiracy. And when Khan realized he was losing the support of key military commanders, he launched a bitter battle for political survival. He got thousands of his supporters to hit the streets and paralyse the capital. And, in a desperate attempt to cling to power, he defied the Constitution to dissolve Parliament and block the no-confidence vote — a move Pakistan’s Supreme Court later overturned in a judgment widely hailed for giving a fillip to democracy. As per several reports in the Pakistani and Western media, he made a botched attempt to replace the army chief, General Qamar Javed Bajwa, in a midnight coup with someone more pliant.

Of course, since 1947, the military has been an all-pervading influence on Pakistan’s polity — it has seized power thrice and dictated the country’s political norms. But Khan’s bid to remain in office was breathtaking in its audacity in that it was the first time a civilian leader had openly violated Pakistan’s Constitution for his own political gain. All through his tenure, there were allegations that Khan had manipulated the country’s institutions to harass his opponents and silence his critics — especially journalists. For a former sporting hero revered by the people, elites and masses alike, this was a remarkable comedown as he proved to be no better or worse than the other elites who gamed the system to clutch on to power.

Time and again, sporting superstars have been given the status of demigods, only to be found out as stars with feet of clay like the statue in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream. When the much-respected South Africa captain, Hansie Cronje, seen as a symbol of probity, confessed to having “been dishonest” and taking money from Indian bookies, cricket cried. Michel Platini, one of the greatest footballers of all time who led France to the 1984 Euro championship, is facing trial in a corruption and fraud case. He is accused of defrauding FIFA, world football’s governing body, of $2 million along with the former FIFA president, Sepp Blatter. The cycling champion, Lance Armstrong, became one of the world’s most revered athletes and the poster boy of endurance when, after beating cancer, he won seven Tour de France titles. This was arguably the toughest sporting event in the world; some even compared it to the 12 labours of the demigod, Hercules. But his whole career had been a cycle of lies which he himself revealed to Oprah Winfrey: he had doped in every competition he took part in and won. When the golfing legend, Tiger Woods, was detained for ‘driving under the influence’ that triggered a chain of events which revealed him to be a serial wife-cheater and sex-addict or when the boxing heavyweight champion, Mike Tyson, was imprisoned for rape or the football star, O.J. Simpson, went on trial for murder or, back home, when the steeplechase athlete, Paan Singh Tomar, was marauding the ravines of Chambal and the Olympic medal-winning wrestler, Sushil Kumar, was accused of murder or when the South African Paralympian, Oscar Pistorius, shot dead his girlfriend — the reaction, always, was more of disbelief than anger. Disbelief, because lesser mortals have turned these sportspersons into objects to be deified and worshipped, the human personification of all that is good.

Sachin Tendulkar, arguably India’s greatest sporting icon, has opted for silence during every controversy India has grappled with. Except for a “Mumbai is for all” statement, the Bharat Ratna has chosen not to comment on issues that are seen to be divisive in nature. Last year, he did, and found himself under attack from many after he reacted to the remarks on the farmer protests made by the Barbados-born pop star, Rihanna, and the climate change activist, Greta Thunberg. Tendulkar took to Twitter to say that India’s sovereignty cannot be compromised and that “external forces can be spectators but not participants”, a line that parroted the Narendra Modi government’s stand.

One can argue that at the end of the day sportspersons are human, that they didn’t ask to be turned into role models, let alone demigods. That their success comes with human frailties. But do we expect Cronje to take money to throw a cricket match? Or Platini, that midfield wizard, to stand trial like some slimy crook facing allegations of the kind that he is? As Tiger Woods putted his way to golfing glory, he became a role model for those desperately seeking one — his character, substance and virtue were above reproach, children were told, ‘Be like that man.’ Most of it was, of course, a lie as it became apparent that Woods, aided by a complicit golf media which depended on him for their jobs, had hidden this dark side of the “model man”. In Woods’s defence, it can be said that he never asked to be called the “model man”, but the image was a cleverly cultivated one. It helped him bag lucrative endorsements worth millions of dollars, the best corporate brands queued up at Woods’s doorstep with offers to become their ambassador, he basked in worldwide fame and glory.

It’s time that we stopped worshipping our sporting heroes and saw them just as that. Don’t deify them. Don’t deify anybody.