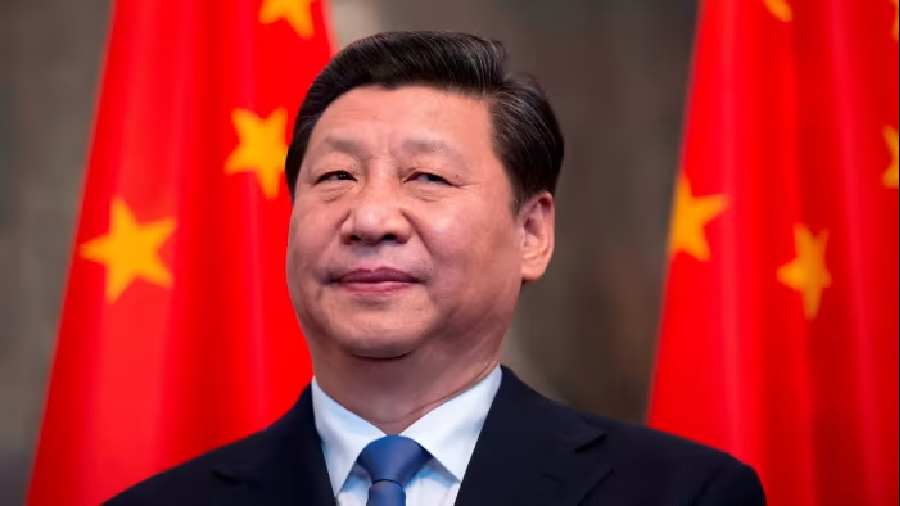

Every five years, the Chinese Communist Party assembles delegates from across the country for its marquee political event — the Party Congress. But the 20th CCP Congress, which starts today, will be different from the previous iterations in ways that speak to fundamental shifts in Chinese politics, which will, in turn, impact the entire world. The party’s general-secretary and China’s president, Xi Jinping, is expected to win a third term at the Congress. Already China’s most powerful leader since Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s, Mr Xi is likely to further cement his authority by elevating more loyalists into the party’s two top bodies, the Politburo and its Standing Committee. For the past three decades, the CCP has followed an informal age rule under which leaders needed to be younger than 68 at the start of a Congress to be on the top-two party bodies. But in September, new rules were released, with age no longer a priority. Mr Xi himself is 69; so this change, in addition to facilitating his stay in power, will give him more flexibility in personnel choices.

Still, for all the power that he has accumulated, Mr Xi faces challenges and the CCP a looming leadership struggle. Since the 1980s, the party has been careful to promote a concept of collective leadership that has helped guard against personality cults and has served as a check against policy excesses. This collective leadership has been reflected in the make-up of the Politburo and its Standing Committee, with members of different political factions represented, and in the anointment of the next generation of leaders. Mr Xi has broken with that model decisively. While the party’s top bodies will still have elders who do not owe their political careers to Mr Xi, no one is being groomed to lead the country after him. The resulting succession void could set the stage for a contest among different power groups within the party in subsequent years.

All of this will carry implications beyond China. Mr Xi’s crackdown on multiple sectors of the Chinese economy and his zero-Covid policy have slowed down the world’s second-largest economy. There are no signs that he will change course, especially if he feels he has been given even greater authority after the Party Congress. A slowing Chinese economy affects almost every country that counts on that nation for goods or as a market. A stronger Mr Xi might also feel he has the mandate to take bolder decisions on foreign policy. India, Taiwan, Vietnam and other nations locked in territorial or existential contests with China will need to watch out. Tensions between the United States of America and China are almost certain to sharpen as they compete everywhere, from the Pacific Islands to Africa. As history shows, and the present confirms, a leader with more centralised power does not translate into a stronger country. It does, however, usually mean a more unsafe world.