Gaganendranath Tagore has a fleeting presence in Mohanlal Gangopadhyay’s book, Dakhhiner Baranda. That is perfectly understandable since Gangopadhyay’s primary focus was on Gaganendranath’s equally illustrious brother, Abanindranath. However, Gangopadhyay does not deny his readers occasional glimpses of the older Tagore. There are, for instance, references to delightful exchanges among Gaganendranath and his younger siblings, Samarendranath and Abanindranath, on that second-floor balcony. Gangopadhyay also mentions Gaganendranath’s fascination with toys. But there is not much by way of his artworks, one of which has, in recent times, been resurrected on social media to coincide with the onset of the festive season in Bengal.

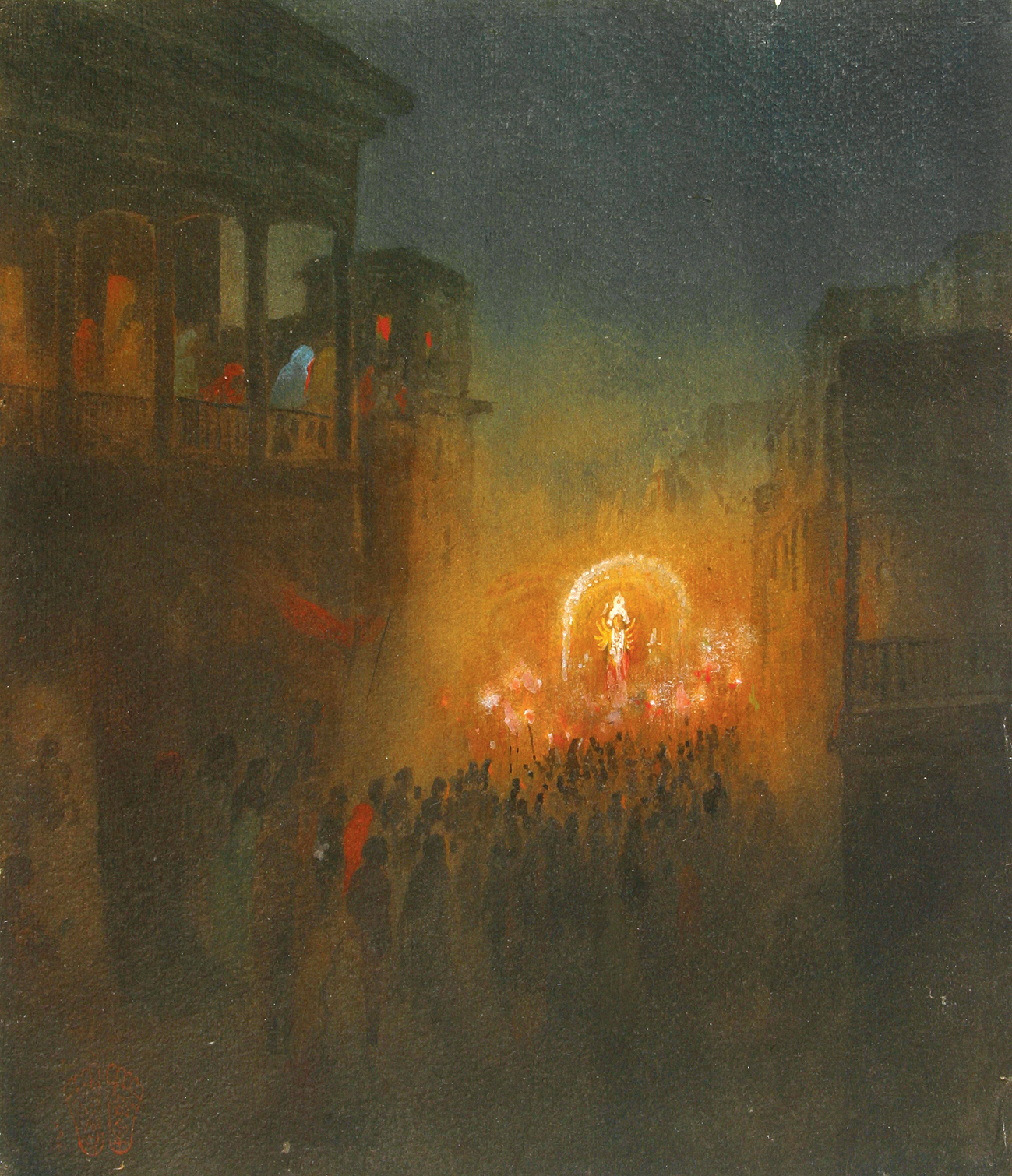

Visarjan, depicting an immersion procession, is said to have been painted between 1915 and 1920. The contrast between darkness and luminescence, characteristic of Gaganendranath’s style during a particular period, is engrossing; the departing goddess is at the centre of an incandescent orb, as it were, while the figures of revellers — men and, possibly, women — remain dimly lit. (The image being circulated on the internet appears to be an embellished version, disturbing this delicate balance between light and dark.)

In his essay, “The Painter of Modern Life”, Baudelaire contended that the goal of modern art and its practitioners ought to be to capture all that is at once fleeting — “the passing moment”— and transcendental. Visarjan’s roots, it could be argued, are modern in this sense. For it records a moment in passing: an immersion procession. But what it saves for posterity in the mind’s eye is something sentient that transcends that solitary speck in time: a sense of anxiety evoked by a chaotic — but democratic — phenomenon that remains peculiar to Bengal’s cultural landscape. To segments of the Bengali intelligentsia, the bhashaan and its paraphernalia — dancing and inebriated excesses — are yet to be fully neutered of genteel terror. They are, in this feverish imagination, the signal of a temporary collapse of entrenched segregation, comparable to Rome’s barbarians-at-the-gates moment. Yet it has also been argued that the Pujas and bhashaan are representative in nature, offering a transient glimpse of a broader, inclusive fraternity.

Bengal’s Marxists — especially their bhadralok patrons — in power for over three decades since the late 1970s, found a way out of this dilemma through negotiation. While denouncing the Pujas and describing its ritualistic exuberance as a source of cultural contamination, they were not hesitant to capitalize on the event’s apparently public credentials. What else can explain their logic of setting up stalls selling Marxist literature near pandals, a sight that is yet to be expunged from Calcutta’s public spaces?

Indeed, negotiation among competing motives underpins the history of the Pujas. Tapati Guha-Thakurta’s In the Name of the Goddess, a deeply researched, richly illustrated and informative volume, dissects the layers within this strategy of negotiation with admirable precision. Guha-Thakurta argues that one kind of confrontation — can there be any negotiation without conflict? — pertained to the contest between constituents of the civic apparatus (the police, fire brigade, electricity companies, environmental regulators and law) and Puja organizers who, it is claimed, represent the community. The negotiations are spirited: Guha-Thakurta writes that “... notions of civic rights and obligations, like those of licences and limits, remain highly fraught in this domain of popular festivity. What keeps surfacing are contesting definitions of the ‘public’ and the ‘civic’...”

Another kind of confrontation unfolds within. The commercialization of community Pujas has fuelled a collective yearning for, what Guha-Thakurta terms, “a once-pristine form of the Pujas”. This nostalgia has benefited the Pujas of Calcutta’s banedi baris, the repositories of tradition and aristocratic sensibilities, in particular. What makes this nostalgia ironical and complicated in equal measure is that memory, in this context, serves as a sieve, filtering out inconvenient truths to introduce an element of distortion in this collective reminiscence. For the inception of the sarbojanin (universal) Durgotsav — journeying from banedi to barowari to emerge as sarbojanin — can be traced to a backlash against the exclusivity of the barir pujo, which, till the mid-nineteenth century, was the monopoly of Calcutta’s affluent families.

But has this negotiated freedom from banedi trappings given the Pujas that coveted communitarian edge? Guha-Thakurta’s inference is unambiguous: “While the Barowari Pujas brought a distinct change in the social community of the festival, they left largely undisturbed the involvement of various artisanal castes and service-providers in the conducting of the ritual event, without ever integrating them into the civic life of the celebrations.” Guha-Thakurta writes that there is a paucity of credible research to explore whether the sarbojanin Puja has subtly reinforced or rejected comprehensively these forms of exclusion. Perhaps an inference can be drawn from the following facts. The claim of Calcutta’s Pujas to be sarbojanin is, arguably, borne out by numbers. Over two thousand pandals had been erected in the city this year. Yet, there remains a perceptible inertia to disturb or, more importantly, realign iniquitous equations. It would be interesting to find out how many Puja committees are willing to accept the services of a learned priest who is a Dalit, or, for that matter, a woman, or a member of a sexual minority. How many Muslims — they make up nearly 30 per cent of the state’s population — are invited to partake of the Navami bhog, a feast that supposedly nourishes the idea of the community?

What has been discernible in recent times is the eagerness of Bengal’s liberal constituency to hold up the Durga Puja as a deterrent to the march of majoritarianism across India. Sharod is noticeably the season to churn out examples of Pujas, from the city and the districts, that are participatory: Murshidabad’s Lalgola, Burdwan’s Dharan and Calcutta’s Kidderpore and Beniapukur, among others, have been cited as exemplars of a precious syncretism. What is not examined in the urgency is the potential of such sporadic participation to seriously challenge the embedded lines of differentiation. Durgotsav is apparently a glue that makes the community stick. But can not the glue be an adhesive to preserve status-quo?

It is true that the Pujas have, since its inception, opened up newer kinds of spaces and relationships through negotiation. But political encroachment — be it Mamata Banerjee’s doles to clubs or the Hindu Janajagruti Samiti’s vociferous objection to an advertisement campaign, imaginatively titled ‘Pet Pujo’, showing the cooking of meat during the festival this year — now threatens the potency of such parleys.

One wonders whether Gaganendranath, if he had been alive, would have painted a contemporary scene of visarjan. The sight of the goddess being towed in front of the chief minister in an obedient file is perhaps the final nail on the sarbojanin coffin.