In Mahender Chawla versus Union of India, the Supreme Court had asked the Union government to present a draft witness protection scheme in recognition of the need for a witness protection regime in India. The ministry of home affairs promptly filed a scheme prepared by the National Legal Services Authority. It was later ordered to be enforced in its entirety throughout India by the apex court under Articles 141 and 142. A crucial bill was thus approved by circumventing the legislative process, which ensures discussions among various stakeholders and interest groups.

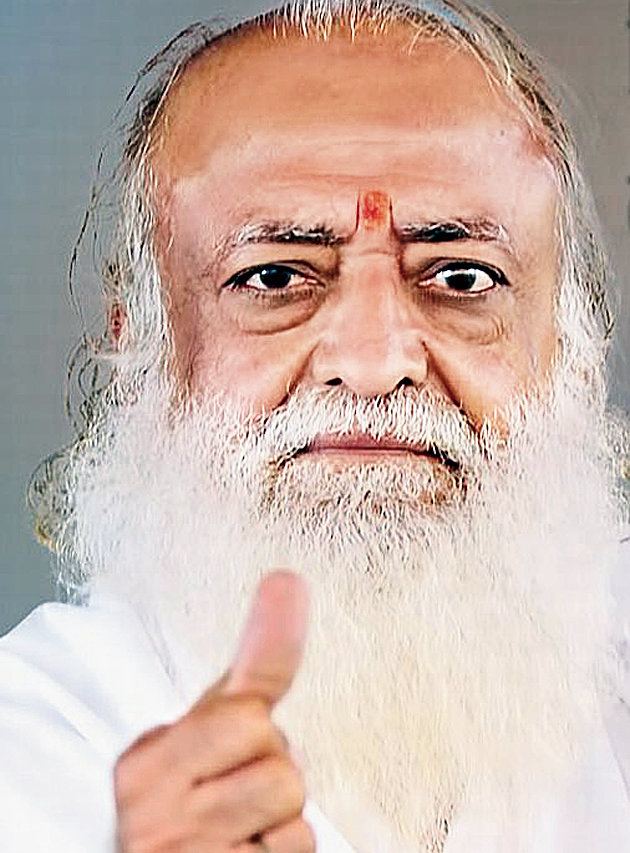

Complainants, investigative agencies, the prosecution and other State agencies work hard to find witnesses to provide evidence in criminal trials to establish the guilt of the accused. Witnesses are also provided security. However, in spite of these arrangements, witnesses turn hostile. Each such instance — the Jessica Lal murder case and the Asaram Bapu rape case can be cited as examples — has subverted the process of justice. Worse, the scale of the problem has been increasing in recent years. In the Sohrabuddin Sheikh case, the Central investigating agency examined 135 witnesses, out of which 85 turned hostile.

The only remedy, as suggested by courts, victims and the prosecution, is to have an effective witness protection regime. In the United States of America, the Federal Witness Security Program, an independent agency, not only helps relocate witnesses who are under threat but also issues new identities to them. It works under the authority of the attorney general. The Witsec has successfully protected approximately 18,865 participants from intimidation and retribution since the programme began in 1971.

The witness protection scheme is the first attempt in India to protect witnesses. But it suffers from serious limitations. The foremost problem is the time frame of protection. The scheme has limited the scope of protection for three months at a time. This renders it redundant as the possibility of threat from the accused cannot be eliminated once protection is terminated. Putting a cap on the duration of protection is akin to providing temporary protection at a premium. Witness protection should be provided until the threat has ceased to exist.

The second drawback pertains to the categorization of witnesses according to threat perception. No scheme can succeed if a corrupt administration or police department is invested with the authority to assuage the threat perception and then categorize witnesses on the basis of its assessment.

Lastly, even though the scheme is committed to protecting the identity of witnesses by maintaining the confidentiality of personal information, it does not penalize any violation of the said provision, reducing the potency of the provision. An effective deterrent must be put in place to prevent the disclosure of such sensitive information.

Owing to its major loopholes, the witness protection scheme is unlikely to instil confidence in witnesses. Neither can it resolve the problem of witnesses turning hostile.

In the Best Bakery case, the Supreme Court had recognized that political patronage and corrupt practices have a role to play in witnesses turning hostile. Witness protection requires foolproof mechanisms. It is possible that the existing scheme would have addressed the problems embedded in it if the provisions were deliberated upon by the stakeholders. Such a procedure, however, was surpassed. In its current form, the scheme is a disservice to the cause of witness protection.