Academics debate what the Bengali bhadralok is like and what his role has been in Bengal’s politics and society. Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee fitted the stereotype more than most politicians of his time — a middle-class background, honest and simple living, love of literature and a passion for liberal values and causes. Generally speaking, the bhadralok could argue endlessly on Marxian theories of capital but would have little idea of how capital worked in real life. It was much the same for the man who felt more comfortable with Marx, Mayakovsky and Marquez than with money matters.

When such a man is seen as the poster boy of capitalism, it is more than a simple transformation — you are tempted to call it some kind of a metamorphosis. In the 1990s, much talk about Bengal’s politics revolved around the question, who after Jyoti Basu? Bhattacharjee was the obvious choice, most people agreed. After all, he was the Number Two man in Basu’s cabinet and enjoyed full support of his party, the Communist Party of India (Marxist), which at that time had Anil Biswas, his lifelong friend and comrade, as the Bengal unit secretary.

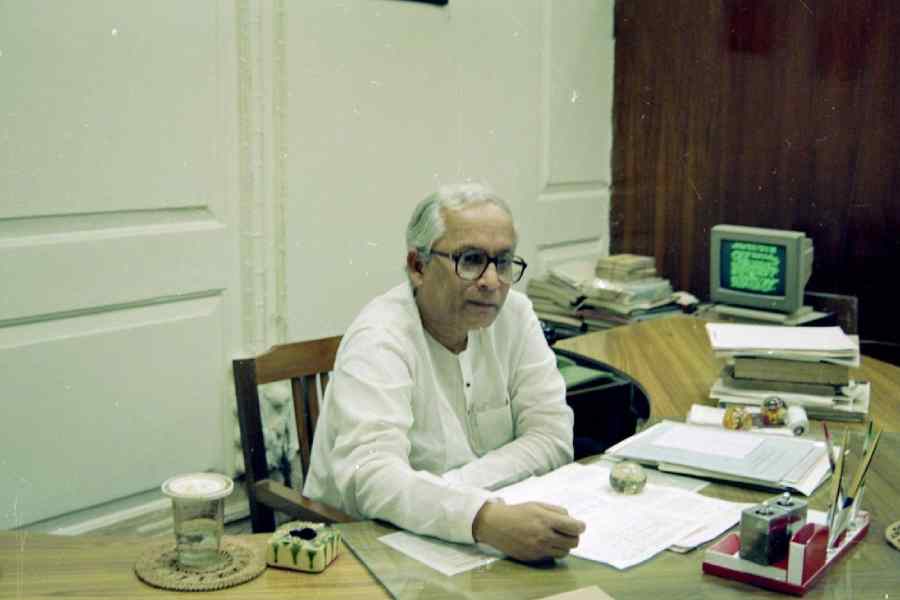

“Who? Me? On that chair?” Bhattacharjee had exclaimed when I met him in his office at Writers’ Buildings, preparing for the story for the Delhi paper with which I then worked. Somnath Chatterjee would be better suited for the job, he hinted. I was surprised to hear that from him — he could not have been unaware that Chatterjee may have been close to Basu but could hardly be accepted by the party for the top job because he was rather ‘aristocratic’ and not likely to take orders from lesser men like Biswas, Biman Bose, and Subhas Chakraborty.

But why wouldn’t he step into Basu’s shoes? What he told me was perhaps half in jest: “Sitting on that chair requires you to make all kinds of compromises. I can’t deal with the business people the way the chief minister’s chair demands.” He wasn’t being just facetious. His party was not only clueless about the ways of commerce and industry but also took great leaps to destroy Bengal’s industrial legacy.

But when he did take over from Basu, he embarked on what seemed to be a mission impossible. He had to change not only himself but, more important, his party and its rabid anti-business image and its policies. True, Basu too made a beginning with the Left Front government’s 1994 New Industrial Policy but he gave in to party hawks far too often and far too easily.

With Bhattacharjee, it was a different game. The man had his weaknesses, but few doubted his passion and sincerity. Sometimes, he would get too carried away by his newfound zeal of attracting business for Bengal to see the complexities involved in the task.

I remember how he beamed with joy when, in Jakarta in 2005, his government signed several MOUs with the Salim Group of Indonesia for some projects in Bengal. “It’s the happiest day of my life,” he told Indian journalists who went there to cover the event. He brushed aside remarks that the communists in India once hated Indonesia for the massacre of hundreds of thousands of comrades of what then was the world’s second-largest communist party.

The same dramatic change marked his meeting with Henry Kissinger and the former US treasury-secretary, Henry Paulson, who came to Calcutta to try and persuade him that the central leaders of the CPI(M) must also change their anti-Americanism. It was a far cry from the time when leftists in Calcutta burnt effigies of Kissinger and Robert McNamara for the American massacre of communists in Vietnam and Cambodia. Leading American and other foreign publications ran cover stories on the reformed communist from Bengal.

At home in Bengal, businessmen gave him the kind of approval that Basu never got. Initial doubts soon gave way to genuine cheers among the sceptics in industry circles. I recall his triumphant smile on the day of the result after the Bengal assembly elections in 2006. A letter from Ratan Tata, promising the small car project in Singur, was the first thing he brandished as a signal for a ‘new Bengal’.

As he reached out to investors, he also waged a battle with his own party and its militant trade union, the CITU. He tried to clean up the mess created by the party and its teachers’ organisations in education. So drastic were some of his actions against party sceptics that they took their complaint to the then-retired Basu, hoping that the latter could rein in Bhattacharjee.

But his two missions — of bringing business back to Bengal and of mending his party’s ways — remained impossible in the end. Not long after he hoped that the Tata project in Singur and a proposed petrochemical hub at Nandigram would be his twin triumphs, they turned out to be the twin towers of the coming collapse. The party’s withdrawal of support from the UPA government at the Centre in 2008 on the issue of the Indo-US civil nuclear deal showed the limits of his struggle with the party.

Yet, his full-blooded campaign for new industry was not without its justification. The Left Front’s earlier programmes of land distribution and empowerment of poor people through the panchayati raj had worn themselves out. Bhattacharjee and his party argued that industry was the only hope for Bengal’s massive army of the unemployed. But he had little viable idea of how to find land for new industries without alienating the peasantry, particularly the marginal farmers. His drive for industry was an attempt to make a virtue of necessity.

But it unleashed political and other forces that Bhattacharjee didn’t quite know how to control or even fight. And the biggest of the forces was none other than Mamata Banerjee, his main challenger. When 14 people were killed in police firing in Nandigram, the endgame for Bhattacharjee began. Neither he nor his party could turn the tide back. Mamata Banerjee managed to turn her Singur-Nandigram agitation into something of a wave, which drew in its fold not just her Trinamool Congress but also people from all walks of life, especially the intellectuals and even leftists of various hues.

However, there is no irony in the fall of a politician who was perhaps one of the cleanest of the tribe in India and who promised a new beginning. The Left rule in Bengal was so old — 34 uninterrupted years — and the Left ideology was such a lost cause in the post-Soviet Union world that Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee had no way of winning the battle. But the man will be remembered for daring to dream.

Ashis Chakrabarti was a senior editor with The Telegraph