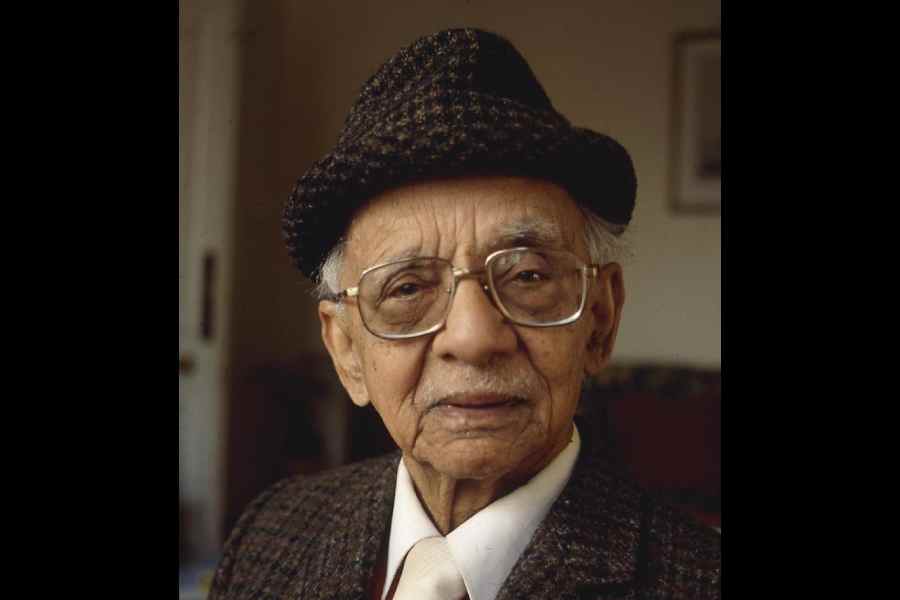

As India hurtles towards a predicted apocalyptic election, the question is not whether the Bharatiya Janata Party will score another resounding victory but how it will use its triumph. That uncertain future recalls my first meeting in 1962 with Nirad C. Chaudhuri. As I wrote in a centenary tribute in Time magazine 35 years later, Chaudhuri sought my opinion on a scattering of tents across the road from the balcony of his flat near Delhi’s Kashmiri Gate. I said they housed construction workers who would go away when their job was done. “No!” he exclaimed vehemently. “They will never go away. That is Hindu India coming into its own!”

He did not have in mind the benignity of Rudyard Kipling’s short story, The Miracle of Purun Bhagat, in which the author rebuts racism accusations by affirming that “so long as there is a morsel to divide in India, neither priest nor beggar starves.” The title of Chaudhuri’s last volume of memoirs, taken from Alexander Pope’s “Thy hand, great Anarch! lets the curtain fall;/ And universal Darkness buries All”, hints at a more sinister conclusion. He may even have come to believe in Churchill’s theory of a conspiracy of “Brahmins who mouth and patter the principles of Western Liberalism, and pose as philosophic and democratic politicians… [but] deny the primary rights of existence to nearly sixty millions of their own fellow countrymen whom they call ‘untouchable’, and whom they have by thousands of years of oppression actually taught to accept this sad position.”

The long overdue provision for fast-track citizenship for beleaguered Hindus from several neighbouring countries gives some indication of Narendra Modi’s threatened “big decisions” during a third term that is almost taken for granted. Many supposedly revolutionary changes are bound to be little more than semantic. For instance, ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ only repackages Jawaharlal Nehru’s familiar ‘import substitution’ mantra while the original of the proudly advertised ‘Amrit Bharat Station Scheme’ must seem even more repetitive since the first passenger train between Bombay and Thane in 1853 obviously needed stations. So did the East Indian Railway’s Calcutta-Delhi link line finalised by 1846. The drive for ‘Akhand Bharat’ may no longer hold central position in the BJP’s thinking just as consolidation of the sad remains of Gulab Singh’s kingdom of Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh may seem more important now than getting back ‘Pakistan-occupied Kashmir’.

However, Uttarakhand, home to revered Hindu temples, and Himachal Pradesh, with the plainly modern imprint of an outsize pair of feet on Jakhu Hill, might set the ball rolling for an inclusive definition of the loyal Indian. The three new laws overhauling the criminal justice system might make life easier for everyone by simplifying court procedures, reducing demands for extra-legal gratification at every turn and by plugging loopholes. All such advances in bureaucratic procedure, science and technology, transport and infrastructure, even the “astronaut wings” that Modi presented recently to four pilots at the Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre, are indebted to earlier achievements even if few in today’s India are modest or honest enough to admit like the eminent British scientist, Isaac Newton, that “if I have seen further [than others], it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” The VSSC was established a year before he died by Nehru, one such giant, who reminded the Ceylon Association for the Advancement of Science that “politics and religion are obsolete; the time has come for science and spirituality.”

Nothing could have underscored the difference between the two Indias more emphatically than Modi’s announcement after his underwater puja, “I felt connected to an ancient era of spiritual grandeur and timeless devotion.” His benediction, “May Bhagwan Sri Krishna bless us all”, injected a note of piety in a cause that appears to elevate statecraft to the level of the gods. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi knew that the deadly mix of politics and religion is irresistible to South Asians. So must Modi who probably finds it greatly diverting when such unlikely acolytes as Mamata Banerjee and Rahul Gandhi scurry around frantically seeking religious credentials.

The tone of Bharat that is India — no longer of ‘India that is Bharat’ — is bound to be very different now that English is not the primary language of either of the ruling party’s two most powerful politicians. English is the language of understatement. It imposes a particularly unIndian restraint on speech and behaviour and must seem especially alien outside the minuscule urban milieu to which this newspaper caters. No wonder the Supreme Court complained in the Patanjali Ayurved case that “the entire country is being taken for a ride and the government is sitting with its eyes shut” as this newspaper reported last Wednesday. Such a disconnect can mean a major upheaval in a society that has rightly or wrongly identified education, literacy and even civilisation with the English language ever since the British took over from the Mughals.

The new India promises to be a mix of idyll and illusion with remote occurrences reinvented in brilliant colours, the immediate past brushed under a fancy carpet, and history enlivened by liberal doses of magic and mythology. Handles and honorifics with sacrosanct overtones — Acharya and Yogi, Swami and Sant — bestow dignity on obscure operators, especially in the absence of any responsible regulatory authority to protect titles from misuse. No wonder the likes of many who brought discredit to khadi are now said to sport saffron.

To be fair, they were not the first copycats. When the scholarly Dr Karan Singh launched his Virat Hindu Samaj eight months after 700 Tamil Harijans converted to Islam to the anger and anguish of Hindu orthodoxy, an ecstatic Swami Satyamitranand burbled in what seemed like holy ecstasy, “The Lord Almighty has sent Maharaja Karan Singh, the great Suryavanshiya Kshatriya, as a divine blessing.” It seemed as if the Virat Hindu Samaj would knit together hundreds of sects and castes. Not since Kurukshetra, people said, had Hindus assembled in such large numbers in the name of religion. Police estimates reckoned on four lakh people at the Boat Club rally. Dr Singh’s message to them was that untouchability was not a part of the dharma but a social phenomenon that could be abolished. “If a Hindu can see the manifestation of god in a tree, a stone and the sky, why cannot he find god in a fellow human being?” he asked amid cheers. The initiative was short-lived. When he wound up the Samaj, Dr Singh explained that he had hoped to strengthen the position of secular Hindus who found it necessary to apologise for their faith. Instead, his organisation was in danger of being taken over by the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and other fundamentalist organisations.

The no longer Unknown Indian may not have been surprised by this retreat of the moderates. Dayanand Saraswati’s Arya Samaj and the less militant but once influential Brahmo Samaj had already fled the battlefield. So in a more signal defeat had Buddhism. With more places of worship to recover and more minority wings to clip, Chaudhuri had already developed his doomsday thesis: India was a massive piston that the British had dragged out and held in place by brute force. The Indians who had taken over after 1947 were clinging to it with aching arms. They didn’t have a hook or rope to secure the piston and lacked the muscle to hold on. “Inch by inch, it’s slipping in. One day their strength will fail, and the piston will slam back with a tremendous roar, plunging India again into the anarchy and bloodshed of pre-British times!”

Does that Kurukshetra await the third coming?