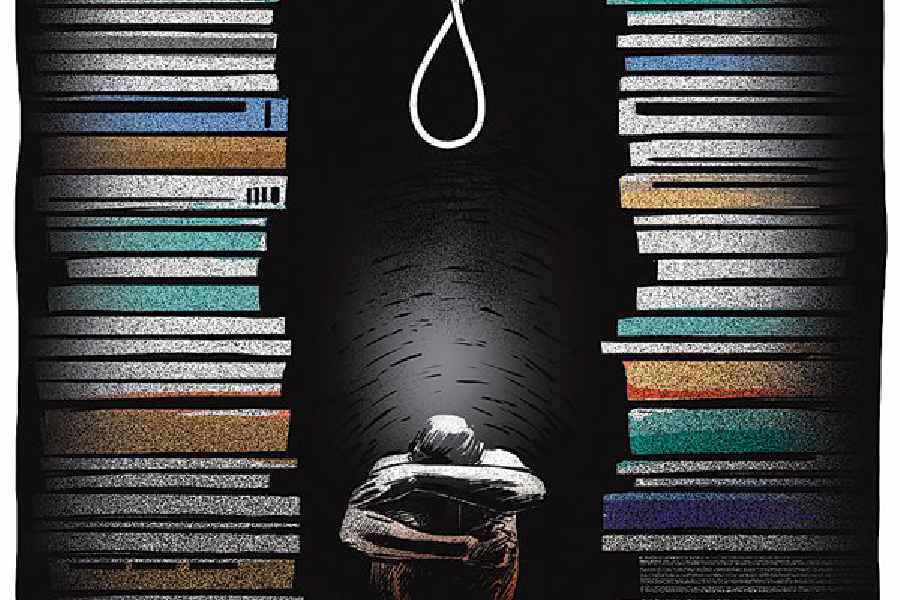

“Onno kothao giye morlei toh paare,” a woman muttered as she tried to shove her way into a bus that was already bursting at the seams. Many on that congested street — office-goers, children returning from school and their mothers, tourists out to enjoy Calcutta’s fleeting winter — may have shared her irritation. The ‘offender’ in question was a man who had died by jumping in front of an oncoming train, paralysing the Metro Railway services. His suicide had brought the Metro services and, consequently, the city to a grinding halt, resulting in the aforementioned woman’s ire. But should there be a place for a person who has decided to take his own life? Where is ‘onno kothao’?

A Swiss citizen would perhaps walk into one of the many assisted suicide clinics in that country, where thorough counselling may actually help him change his/her mind about ending life. Research by the American legal scholar, Richard Posner, suggests that having the option of assisted suicide causes people considering the extreme step to reflect on their decision. Consequently, assisted suicide has the potential to reduce the total number of suicides. Following this, some states in the United States of America went on to legalise assisted suicide. In fact, the number of countries where physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia are permissible in a medical context is on the rise. In the Netherlands, even mental illness is grounds to seek assisted suicide. Twenty-two people under the age of 30 died by euthanasia in 2023 because they found their mental illnesses impossible to live with. But should the right to end life remain contingent upon the legitimacy accorded by health institutions only?

The word, ‘euthanasia’, signifies a ‘good death’ in Greek. However, the notion of a good death seems to have been lost amidst shrill debates where the emphasis is typically on the rights of a person with a terminal disease to die: the choice to end life, thus, is not so much about a ‘good death’ as an escape from suffering.

An elderly couple in Pune is challenging this stance on euthanasia. Iravati and Narayan Lavate have been seeking physician-assisted suicide for nearly a decade now. They have petitioned both the courts and the president but to no avail since neither Iravati nor Narayan is sick; they are just sick of living. The Lavates are not alone in challenging the collective outlook towards a cherished, fundamental ideal — that of a long life. There appears to be an expanding community of people globally — many of them are not yet in their 30s — who would prefer to end their lives at a time and place of their choosing rather than wait for an untoward event, such as climate change, to kill them. On one such community group on Reddit, Maya Akello from Uganda — it is one of the countries that may become uninhabitable due to global warming by 2050 — writes, “I’m not afraid of death, but I’m terrified of the suffering that’s coming.”

Is there then a case to liberate the discussion on euthanasia from its standard medical context and argue that many other possibilities exist when it comes to humans choosing death over life? There is, for instance, the concept of liebestod — ‘love death’ — wherein couples who do not want to live without each other opt for ‘duo euthanasia’. In 2020, 26 couples chose it; the number rose to 32 in 2021 and 58 in 2022. In 2024, the former Dutch prime minister, Dries van Agt, and his wife, Eugenie van Agt-Krekelberg, died by duo euthanasia.

The ideal of individual liberty is also receptive to the right to die. Little wonder then that the English philosopher, John Stuart Mill, in his essay, “On Liberty”, had argued that individual liberty has to include the right to do as one likes with one’s own self — even harm it.