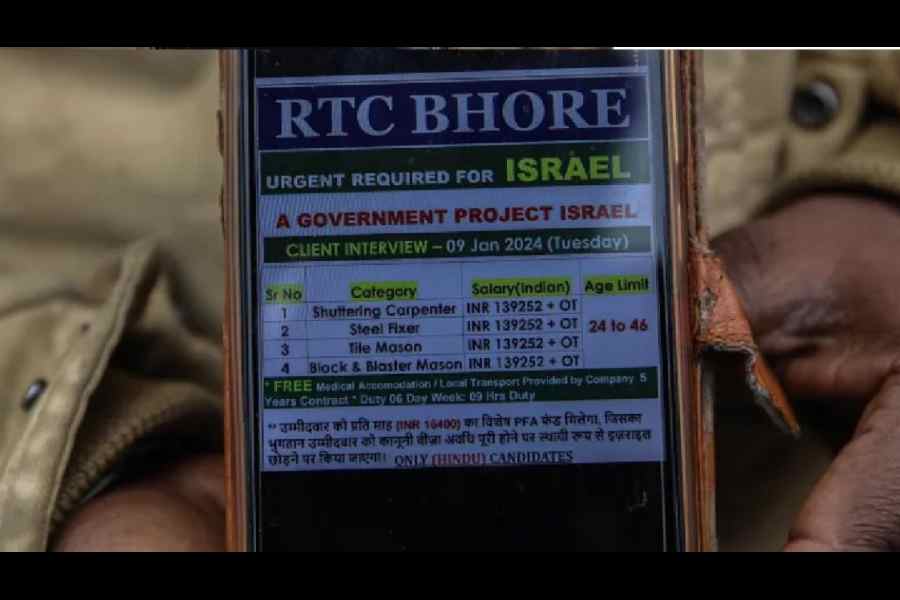

In January, just days after Israel’s war on Palestine had reached its 100-day mark, officials from Uttar Pradesh and Haryana hosted a delegation of 15 Israeli businessmen seeking workers from the two states. Around 10,000 hopeful applicants arrived to gain work in Israel, many waiting for hours in the cold.

In April, the first batch of 64 Indian workers were sent to Israel as part of a bilateral plan to bring more workers to the country facing a dire worker shortage. Following Iranian missile strikes on Israel on April 13, the Indian foreign ministry released a travel advisory for Indian citizens in Israel, urging them to register themselves at the Indian embassy and to “restrict their movements to the minimum.” But such options have not been possible for many of the nearly 18,000 Indian workers currently in Israel.

Agreements to send 42,000 workers from India began a year ago in 2023. In December, the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, personally requested in a call to Narendra Modi to send more than double that number two months after the war began. Attracted by high salaries, Indian workers from some of the country’s poorest regions signed up to leave in droves. But what they find when they arrive is the safety and the security promised to them when they left home is often broken.

Israel is not the only country where Indian workers face dire working situations. Exploitation of Indian workers under conditions akin to slavery in Singapore and the Gulf states has been a long-standing issue. In Serbia, Indian workers have protested over unpaid wages. In Italy, a young Punjabi worker committed suicide after drowning in debts from predatory employment agencies and exploitative employers. Similar stories can be found in Spain and Portugal — of precarious working conditions and Indian workers receiving little to no salary.

But India is particularly ill-equipped to protect migrant Indian workers in places of conflict. In 2014, to cite one example, 40 Indian construction workers were kidnapped in Iraq. But there are reports, some as recent as the last several months, indicating that Indian migrants promised jobs in Russia ended up being sent to fight in the war against Ukraine. India’s Central Bureau of Investigation acknowledges awareness of at least 35 Indian nationals who had been trained for combat and sent to fight in Ukraine. Last year, in Armenia, two Indian nationals were wounded by shelling near the Azerbaijani border during the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

In the case of Israel, workers are being sent as part of bilateral agreements that began last year between Netanyahu and Modi. But such recruitments have intensified since the beginning of the war as Israel’s agriculture and construction economies have long depended on Palestinian labour. After Hamas’s attacks on Israel on October 7, some 150,000 Palestinian workers from the West Bank and another 18,500 from the Gaza Strip lost their work permits overnight when the Israeli defence minister, Yoav Gallant, and Herzi Halevi, the chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces, froze them for

security reasons.

When working abroad in countries in conflict, Indian migrant workers are theoretically required to register with India’s ‘e-Migrate’ system to better account for workers’ safety. Israel is not included in that scheme, nor is Russia or Armenia, leaving Indian workers in those conflict zones at risk. Even more unusual is the fact that while Indian workers in Israel must sign contracts that commit them to work for no less than one year, their work and residency are capped at 63 months.

Israel’s population, immigration and border authority has “consistently assured that no Indian worker will be placed in or near the conflict zone,” an anonymous source told The Times of India. But on March 5, a 31-year-old worker named Pat Nibin Maxwell was killed instantly in a Hezbollah missile attack while working on a farm close to the Lebanon border. Maxwell had arrived in Israel in January, along with thousands of other workers, and now leaves behind his pregnant wife and their five-year-old daughter. Two other Indian nationals working on the farm were also severely injured, while five others sustained milder injuries.

Indian workers are eager to go to Israel and other regions of conflict despite the state of war due to the high salaries offered. A worker in Israel can earn more than 10 times of what he would make at home in India, if he can find work at all at home. Salaries for Indian workers in Israel, on an average, are Rs 1.5 lakh per month. Many workers report spending their families’ entire savings on predatory employment brokers to help secure these contracts.

But on arriving, some workers realise their employers have little incentive to honour their contracts. One worker labouring in a farming community in northern Israel told Foreign Policy that he worked gruelling 12-hour shifts picking produce, including on weekends, and had been told he would be paid far below the legal hourly minimum wage. At the end of the month, he said he was not paid at all; instead, his salary was sent to his employment agency.

Incoming missiles have also been an ongoing problem for migrant workers; Maxwell was just one of the nearly half-a-dozen workers who had been killed in the last decade. Many workers reported that they have little preparation on what to do in the event of a missile attack and that they are under immense pressure to continue working. According to an investigation by Kav LaOved, an Israeli non-profit labour organisation, emergency apps that warn of missile strikes cannot be downloaded on non-Israeli phones. But it hardly matters. Often, in areas close to the front lines, alarms only sound after the missiles strike.

India may be eager to send its precious human resource — its people — to work around the world. But their safety must be adequately protected. Expanding the e-Migrate system to include more countries that have security threats would be a start, as well as making the system a more attractive alternative to workers who would otherwise pay predatory employment agencies out of their pocket. But for now, Indian workers are treated as disposable casualties of war.

Carol Schaeffer is a journalist based in New York and Berlin from where she writes about Europe, politics and culture