I’ve been watching a lot of films on the various OTT platforms. Besides showing you new films, platforms such as MUBI also allow you to take your pick from old favourites and classics that you’ve maybe seen long ago, and recently I found myself clicking on all sorts of gems from the past. Watching some of these films on my laptop screen is a strange experience. It’s not an exact analogy, but I did find myself thinking of peering at one of those tiny-printed, miniature versions of books, re-reading the ones that you’ve first read in a properly-sized volume. After a lot of such viewing, something also felt a bit off about the fact that I could fast-forward, rewind, pause and go do something or even suspend my viewing of a film for a few days. It occurred to me that from now on, for the foreseeable future, this is how most people would watch films that weren’t on current commercial release. This, of course, took me back to the time when young people of my milieu were discovering cinema in the late 70s.

Growing up in Calcutta, the cinema theatres formed clear groupings in the head: it was a completely different experience going to one of the Hindi film theatres, or to a Bangla cinema hall or to one of the ‘English’ ones. Occasionally, when there was a Sunday morning show of an English film in a Bangla hall it just felt wrong; you went in past the Uttam-Suchitra posters and were wrong-footed by the screen when one of the Hollywood logos came on; you walked out, having almost skinny-dipped with Julie Newmar in Mackenna’s Gold, to find Chhabi Biswas locking eyes with you from the wall. Boarding school in small-town Rajasthan found me missing the comforts of Globe and Menoka, but in clement weather the weekly film screenings were outdoors and we watched them sitting on the red sandstone step-benches of a 19th-century pavilion. The projection on the portable screen was dim, the sound from the single film scratchy, the reel changes were frequent, but behind the screen stretched the cricket ground and beyond that was a peak of the Aravalli hills with the moon and stars moving over it. At the time all this seemed unremarkable, but in the memory it’s the whole scene rather than any one film that stays etched as magical.

Back in Calcutta and attending college, many of us fell prey to the addiction of serious cinema. This meant getting up early on Sunday mornings and hanging around one of the film society screenings, hoping to catch the eye of some older acquaintance and cadging a pass. It seemed there was no question of anyone under the age of fifty-five becoming a member of a film society; as in the most exclusive clubs, membership opened up on a strict priority dictated by death and geriatricity. Occasionally, a kind dada got you one of the hand-printed parchas that allowed you to file in with all the dhoti-kurta clad kinobabus. This permitted you to sit under the honour guard of fans whirring out of the side-walls at the Sarala Roy Memorial Hall or the Calcutta Information Centre, absorbing whatever you could from the grainy black-and-white or faded East European colour of Polish, Czech or Cuban films.

As a student at the old Alliance Française in the spectacularly dilapidated Queens Mansion, one had access to the great works of the French New Wave; the screening room at AF had a pillar almost in the centre and the projector throw somehow magically curved around it like a Zidane pass in constant replay. If you were late to a crowded screening, you spent the evening crushed against the back wall, playing peekaboo with Jean-Paul Belmondo around the dratted pillar. The Chitrabani screening room was small, just a bit bigger than the Seminar Library cubicle in Presidency’s English department, but the selection of films was something you could not easily access elsewhere. By far the best screening venue for art films and documentaries was the properly sloping theatre at Max Mueller Bhavan, but again, getting in was always a challenge. The thing about all these places was that the struggle to get in, the discomforts, the quirks of projection and sound, all added to the sense of having scored a precious viewing experience in an otherwise arid landscape. Obviously there were no VHS tapes, DVDs or internet downloads in the late 70s, nor any sense that these might be around the corner. Therefore you watched each film with a certain intensity, as though you’d been given brief access to a precious manuscript in an exalted library, acutely aware that this might be the first and the last time you were seeing it.

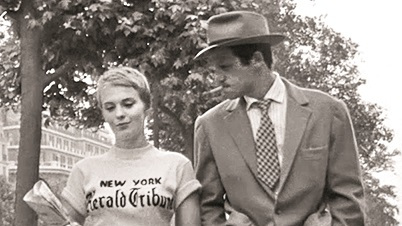

With western music, art materials and many other things, landing in America felt like I’d fetched up in a massive sweet shop, and that too one with affordable prices. There may have still been no inkling of the coming technological deluge, but just by poring over the schedule sheet from Bleecker Street Cinema in New York, you could see all sorts of classics and strange new films being offered with regularly repeated screenings. It was here that I discovered the joys of the ‘double-bill’, where for just a bit more than the (already cheap) ticket price for one film you could sit through two films one after the other. And then, since excess was the middle name of this country, a group of friends could even decide to do two double-bills on the same day. This meant that you’d walk into the theatre at around 10 am clutching your bagel and coffee and watch, say, two early Bertolucci films. Coming out at around half past two, you’d quickly nip over to the deli and get yourself a sub sandwich and a couple of beers in brown paper bags before assuming your seats again. Then, through the pall of tobacco smoke from the last few rows, you would watch two more films, say Godard this time, and come out punch-drunk on jump cuts and Godardian aphorisms at 7 pm, a day well spent, an evening still to be ransacked.

For certain films the theatre would be jam-packed, for others almost empty, as though you were a movie mogul in your own screening theatre. Whatever the number of fellow viewers, whether the seats were full or empty, something about the scale of the screen, the evidence that you were in a site of collective viewing, the silence and its corollary, the respect demanded by the fact of this being a theatre and not someone’s home, affected the way you watched a film. Each screening was, in a sense, a unique performance to which you were submitting, in which you were participating, and though that sense of scarcity from Calcutta no longer hung over you, the viewing was no less concentrated and intense. Conversely true also was that while watching a film in a dark theatre you relaxed and let go of other concerns, you were ensconced in the amniotic fluid of the audio-visual and the only thing that disturbed or nourished you was that which was unfolding on the screen.