India is up for grabs. A minister is accused of building illegally on tea garden land; the 21-acre sprawl of Calcutta’s prized Agri Horticultural Gardens may be the next target of criminal rapacity disguised as ‘development’, that much abused word that has sneaked into and corrupted all Indian languages; news reports bristle with imposters swindling the unsuspecting out of their life’s savings. Emails scream for help. A mother wails that her daughter will die unless treated at once, a father pleads he cannot afford to continue his son’s schooling. Banks warn of fraudsters. There is no concealing the threadbare social fabric of a country awaiting the 74th anniversary of Independence.

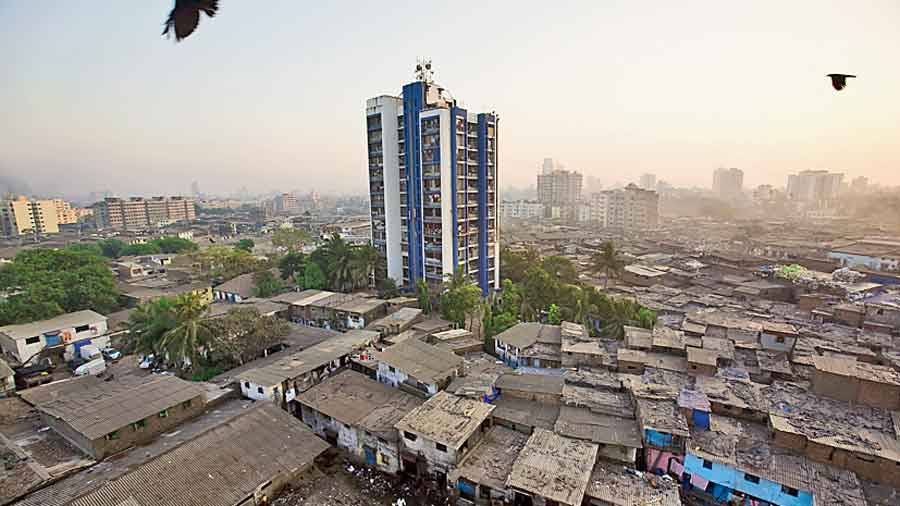

What The Economist calls India’s “Billionaire Raj” sprouted 40 new billionaires during the pandemic while 230 million more workers and villagers grovelled in the dust of jobless penury. Narendra Modi accused the Opposition of “insulting” democracy as his government adopted 12 bills by voice vote without debate in less than seven minutes. A former MLA charged with arson was welcomed into the Bharatiya Janata Party; the BJP MP whose house he is charged with firing (both were then active in other parties) said she was “stunned”. Health and education remain the most neglected spheres of official responsibility, presumably because politicians cannot wring any dividend from them in the short run. Pictures of the dead and dying, of coronavirus patients gasping for breath outside hospitals too packed to admit them, jostling for oxygen cylinders, cremation fires smouldering night and day, and the Ganga heavy with bloated corpses competed with illustrations of the proposed Rs 1,000-crore Ram temple at Ayodhya and the Central Vista project estimated to cost Rs 20,000 crore. The veteran diplomat, Jagat Singh Mehta, foreign secretary from 1976 to 1979, thought Singapore was “the only former colony to make a success of independence.”

Other countries also sometimes stumble in the first flush of self-government. Some, like Myanmar, squander their inheritance even more flamboyantly. But India’s progress is steadily downhill. Calcutta’s La Martinière, my old school founded in 1836, plagued by resignations, dismissals, pecuniary allegations, lawsuits and, now, even apparently by a replica school, seems to mirror the present-day plight of many hoary institutions that worked smoothly for some years after 1947. Unfashionable though he be, Winston Churchill’s prescience comes to mind each time I get less and less petrol for my 500-rupee note. “Power will go into the hands of rascals, rogues, and freebooters,” he warned. “Not a bottle of water or loaf of bread shall escape taxation; only the air will be free...” Some of his doubts were shared even by a well-wisher like Philip Mason who regretted after 19 years in the Indian Civil Service that Garhwalis imagined a motor road would solve all their problems “just as many people thought independence would solve the problems of India”.

Those idealists expected selfless patriots to take over the reins of government and rule for the public good. They did not take into account the venality that exploded in the great ghee scandal of 1917 when Lord Ronaldshay, Bengal’s governor, noted the “electrifying” spectacle of nearly 5,000 Brahmins desperately cleansing themselves by the Hooghly because the pious Hindu traders who monopolized the ghee trade (and whose successors brandish the Hindutva flag today) did not scruple to adulterate ghee with tallow from forbidden meats. Nor did they anticipate the electoral numbers game throwing up a larger-than-life latter-day Ozymandias, king of kings, to dissipate public funds for posterity to “Look on my works ye Mighty, and despair!”

Being an earthy politician with his ear to the ground, Churchill spotted “the crowd of rich Bombay merchants and millionaire millowners, millionaires on sweated labour” surrounding Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. “What are they doing there, these men, and what is he [Gandhi] doing in their houses?” Churchill wondered. He answered himself. “They are making arrangements that the greatest bluff, the greatest humbug and the greatest betrayal shall be followed by the greatest ramp” in a future scarred by “[n]epotism, back-scratching, graft and corruption in every form”. Churchill’s miscalculation was to equate post-British India with China, which he stupidly dismissed as a “barbaric nation”. But ever the pragmatist, he would probably have welcomed Britain’s current dependence on Chinese investment, trade and tourists as readily as he later hailed Jawaharlal Nehru as the “Light of Asia”. He might even have acknowledged that the thin veneer of parliamentary protocol that passes for Indian democracy has no bearing on political morality, administrative competence or economic growth.

A shocking non-system of public schooling, neglected medical care, and stagnant employment opportunities explain the stampede to migrate to Britain, Australia and the United States of America. This constant exodus of talent is the most damning indictment of India’s failure as a modern nation state. Ostentatious statuary and reinventing perfectly serviceable existing wheels with grandiose civic architecture are shameful distractions like counting the same heads of expenditure over and over again in so-called relief packages. Snooping, over which the 15 Opposition parties are so exercised, is also obnoxious but as ancient as Statecraft even if the Pegasus spyware is more sophisticated than any previous apparatus. At one time, the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, Spain's prime minister, Mariano Rajoy, and the Brazilian president, Dilma Rousseff, were among dozens of global leaders whose telephones and emails American intelligence agencies tapped when they were not listening in on the private conversations of their own president, Barack Obama. Nehru didn’t write a letter for posting in India for 25 years without realizing it would be read “by some secret service censor”. He knew, too, that all his telephone conversations were tapped. Ironically, a British historian later disclosed that Nehru’s own intelligence chief, B.N. Mullick, “remained remarkably close” to MI5 even after political relations between New Delhi and London became chilly.

Official duplicity and secretiveness certainly deserve exposure but the lack of thrift, decency and objectivity in governance does more practical harm than breaches of notional democracy. The persecution of civil servants who may not toe the line, the favours showered on those who do, the studied avoidance of the media, and the scorn for legislative propriety evident in the refusal to answer the Opposition’s questions do not enhance respect for authority. Whether or not democracy is the worst form of government except for all the others, it is not an end in itself. It is the means of sharing authority, distributing wealth equitably, and achieving what Bhutan’s king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, dubbed “Gross National Happiness”. It cannot coexist with the contempt for the multitude implicit in the comment by Narayan Prasad, a BJP legislator in Bihar, that since “common people mostly use buses” they are not affected by spiralling petrol prices and will “get used to it” if they are.

Such episodes reveal an utter disrespect for the public, both individually and collectively. A similar disregard might explain rumours of the Life Insurance Corporation of India being privatized. Normally, private ownership means vigorous growth but dismembering the LIC would risk hundreds of crores of investment and threaten the savings of some 300 million policyholders. It would be like allowing avaricious businessmen to make money out of the garden that is the proud legacy in Calcutta of William Carey who founded India’s first degree-awarding university, translated the Ramayana into English, and the Bible into Bengali, Oriya, Assamese, Marathi, Hindi and Sanskrit.

Politicians can afford to treat people with disdain by pandering to the most retrograde prejudices of the lowest denominator of majority opinion. They have the “Billionaire Raj” behind them: it shares the loot for India is up for grabs. There is little to celebrate this August 15 as the country trembles on the brink of a third wave complicated by the Delta variant and, possibly, other deadly mutations.